The associationism and the emergence of policies related to RDs, both in the international context and in Spain, are related to and influenced by a multiplicity of social factors and cultural changes that have been taking place since the 1980s. In fact, the social and health problems caused by the Toxic Oil Syndrome (TOS) also led to the creation of associations of those affected, whose main objective was to create public opinion and pressure political groups to achieve their goals. In this sense, the process of social reflexivity and personal self-determination, together with the proliferation of diverse political discourses, as well as the elaboration of legislative norms show the transformation of values and beliefs. In the case of Spain, the transition from Franco’s dictatorship to democracy brought with it a significant social transformation.

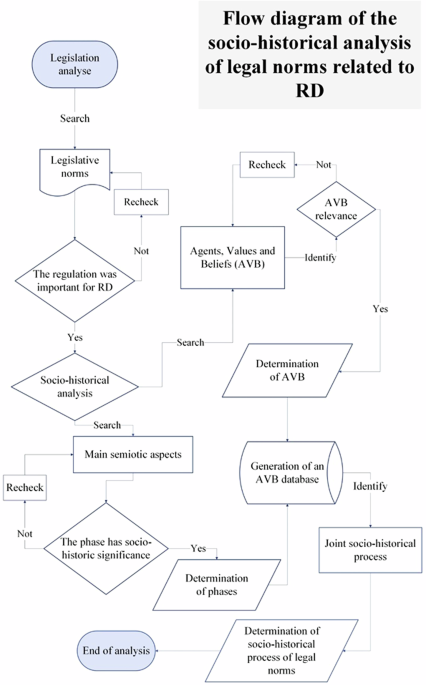

An interesting approach that has helped to understand this type of phenomenon of convergence of interests and coalitions is the ACF (Nohrstedt and Heinmiller, 2024). Coalitions between associations of people affected by RD, either among themselves or with political agents, have gradually reshaped elements of the health system, as well as the social perception of social reality. These changes can be exemplified by the health policies implemented in recent years. These policies clearly show the transformation of values and beliefs about.

In the late seventies and early eighties of the twentieth century, there was a significant transformation in the health systems of the so-called “West”. The first paradigmatic example can be found in the United States of America, where Abbey S. Meyers (2016) shows how she fought for people with RD to have more possibilities of access to medications. This social struggle led President Reagan to sign the first law promoting orphan drugs on January 4, 1983. This law, known as the “Orphan Drug Act”, already makes clear reference to orphan drugs. This law makes clear reference to so-called RDs and conditions and the orphan drugs needed for those affected. Subsequently, Meyers with other affected people set up the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) in the region as the first organization for people affected by RDs.

The affected associations, in this case NORD, used media support to put pressure on the political authorities and achieve their objectives (Cheung et al., 2004). This strategy was also used as a model in other countries. The second country to implement legislative measures in this regard was Japan in 1993 (Song et al., 2013). Australia was another region that developed, a regulation in the 20th century: Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Act of 1990 (Gammie et al., 2015).

Spain is a particular case because, as we shall see, it generated regulations related to a rare disease, but this did not materialize in any global legislative action. We are referring to the well-known case of TOS with the first cases occurring in early 1981. Now is not the time to go into detail about this event, which was so relevant to the transformation of the health system in Spain, although we mention it to show the temporal coincidence of both sociohistorical events. On the other hand, the 1980s also saw the HIV pandemic, the discovery and cases of hepatitis C infections, as well as a substantial increase in the use of injectable drugs. These biosocial examples are also related to the social concern about health and changes in the political system in the region under study. At that time, there was a transition from dictatorship to democracy in which the perception of freedom was exacerbated, and various structural maladjustments became evident, bringing with them social protests, associationism and volunteerism. As Avellaneda et al. (2007) put it: An unprecedented interest in volunteering and associationism appeared in society in general, which together with the “media boom” made it possible for civil society to become aware of its importance and considerably increased the appearance of the associative movement in the media (Avellaneda et al., 2007: 181).

Before analyzing the SAT case, it is worth noting that we consider that there have been three non-linear phases in the process. In each of them, importance was given to a significant element: health (bio-health perspective); control (political perspective) and money/work (economic and social perspective). As we have just mentioned, these phases do not occur one after the other in a linear fashion. The first one had a more biomedical focus, due to the urgent need to address the problem. Subsequent phases, to be executed concurrently, were designed to prioritize both social and economic considerations, specifically Phase II and Phase III. However, the commencement of both phases was contingent upon the attainment of a certain level of bio-health control over the health crisis.

First episode: The toxic oil syndromePhase I—Bio-sanitary perspective

In 1981 a new syndrome of an acquired nature appeared in Spain. The socio-health problem caused by the TOS showed the stubborn corruption and shortcomings in health surveillance processes. The health problem was related to the adulteration of rapeseed oil that was sold in impoverished areas and outside the existing regulations at the time. After the consumption of this oil, various types of pathologies and deaths began to occur, which alerted the population, political agents and the media.

As a result of media and social concern, the Spanish government at the time took the measure of creating a national program for the care and follow-up of people affected by toxic syndrome (Royal Decree, 1839/1981). This political measure could be considered regulatory, as it modeled the behavior of health institutions by introducing specific measures for the care of affected persons and responding to the need to deal with the epidemic. This policy (developed by the Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Security) aims to “build a coordinating and monitoring body for all issues related to assistance for those affected”. In addition, it establishes a mechanism for relations between health professionals and hospitals that will operate both in and out of hospital. Hence, it institutionalizes an extension of the health system towards society (out-patient care).

The legal norm is structured at three levels (Hernández Martín and Martínez-Pérez, 2011)—national, intermediate and local. In this program, four main agents are fundamentally related−ministry, hospitals, physicians and patients. Its main values were related to control, surveillance, care and attention both inside and outside hospitals. In addition, it had a marked contingent and provisional character which, together with the urgency of the situation, formed a value framework based on immediacy and rapid response to a complex problem. This temporary nature had a specific “date of completion” related to overcoming of the epidemic. On the other hand, although it could be affirmed that a first step has been taken in the formation of social care for those affected, this cannot be within the spirit of the regulation. So much so that, in its first paragraph, it is literally stated:

“To the appearance of the toxic outbreak currently existing in our country, the Health Administration has responded with a set of measures of all kinds: epidemiological, etiological research, clinical action, assistance and inspections, through the ordinary administrative organization of the State” (Royal Decree, 1839/1981: 19695).

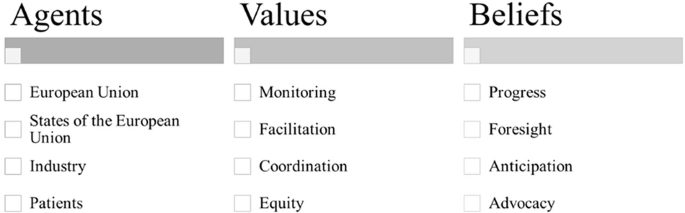

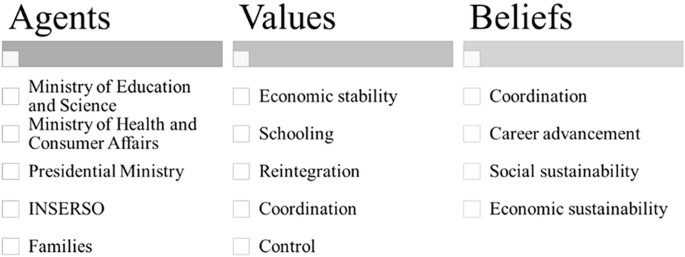

Therefore, it would be more appropriate to indicate that the motivation for this program is fundamentally biosanitary and, secondarily, political in nature. This fact makes sense due to the health urgency and the need for political control inherent to these types of measures. A scheme illustrating all the elements of analysis we are using is shown below (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Agents, values and beliefs of phase I.

Source: own elaboration according to Royal Decrete 1839/1981 (Royal Decree, 1839/1981).

Phase II—Political perspective

In the first phase, we found that the regulation was focused on the biosanitary perspective. Subsequently, it was necessary to restructure the measures adopted. In this sense, R.D. 783/1982 (Royal Decree, 789/1982), determines “an administrative body under the Ministry of Health and Consumption, which is entrusted with ensuring the unity of direction of services, coordination and strengthening in all its aspects the action of the Administration in favor of the affected population group”. In this sense, the measure in question gives greater importance to the political element and its link with the citizens. Likewise, a few months later, Royal Decree (R.D.) 1405/1982, was approved, creating the National Plan for the Toxic Syndrome. The latter establishes the creation of a General Coordinator, with the rank of General Director. The person in this position should control and coordinate the activities of the State in relation to the SAT and “particularly in its health and social aspects, to enhance in all its dimensions the action of the Administration in favor of those affected”.

The National Plan raised the political importance of regulation, as the Plan was part of the Presidency of the Government. In R.D. 1839/1981, the political entity was the Ministry, but now it is the Presidency of the Government. The general coordinator of the plan controlled several general sub-directorates and a specific technical office. In turn, the Plan was structured in Provincial Programs that followed the instructions of the general coordinator. Undoubtedly, the importance of political control and coordination is high. Finally, this plan (Article 8) introduced research entities as intervening agents by allowing the general coordinator the possibility of approving the implementation of research projects and research contracts.

This new R.D. increased political control over the problem and had as its main values those related to governmental action. One of the changes, not strictly related to politics, involved the incorporation of research as a potential element to help those affected, as well as the improvement in the functionality of the political process. However, as was the case with the previous Royal Decree, social agents and the social perspective itself did not have a prominent place. We can affirm that it is plausible to think that the government considered that political action sufficient to meet the social needs of those affected. However, Article 1 of this R.D. mentions actions involving social and educational services, which means a closer approach to society than R.D. 1839/1981. Likewise, in the same month of June, R.D. 1276/1982, was approved, creating economic aid for those affected, which undoubtedly increases support through non-sanitary channels for those affected.

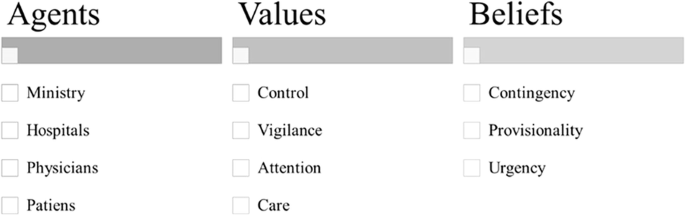

The reason for this shift could lie in the gradual importance of social issues in the political debate. In fact, Hernández Martín and Martínez-Pérez (2011) showed that the session journal from September 15, 1981, included debate on those affected. Especially about their labor, educational, social problems and about the problems generated by the disability produced by the condition. Among the measures discussed were the creation of a census (an aspect that will be maintained for R.D.), the importance of mental health and the attempt to institutionalize concrete and specific measures. All these aspects open the door to a reconfiguration of the conception of the “sanitary system” into a “health system” (Royal Decree 783/1982). A scheme illustrating all the elements of analysis we are using is shown in next image (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Agents, values and beliefs of II phase. Phase III—Economic and social perspective

Phase III—Economic and social perspective

This third phase would be related to the entry into force of R.D. 1276/1982, which complements the aid to those affected by the toxic syndrome. This R.D. establishes various economic and social measures. On the one hand, there is a “complementary family economic aid” with the aim of guaranteeing a minimum income. On the other hand, it is established that children under 14 years of age can also receive another economic aid for “nutritional dietary purposes”. Thirdly, collaboration measures are established among agents to achieve the social and labor reinsertion of those affected. Additionally, measures are also taken in relation to the schooling process of those affected, as well as aid for school canteens, school supplies, etc.

In this new R.D., the National Institute of Social Services (INSERSO) acquires greater relevance as an agent of social protection. In fact, the fourth article of this regulation indicates that those affected will be included in collaboration programs (existing or promoted by the National Plan) with this entity. This fact is of crucial socio-historical importance as it establishes a more defining process of institutionalization. In fact, as we will see later, this institution will end up containing an organization of great relevance for RDs (we are referring to the State Reference Center for the Care of People with Rare Diseases and their Families).

Another important aspect promoted by this R.D., which had not appeared until then, is the involvement of the Ministry of Education and Science and, therefore, the educational system. In this regulation, explicit reference is made to a Schooling Plan that would implemented through the Order of development issued by the Ministry of Education and Science (1982). This Plan is aware that the schooled and affected persons could be in four situations: regularly attending class, having irregular attendance, they could be unable to attend class or be hospitalized. For each of them, measures were taken to provide care, compatibility and contact between teachers and students in case of hospitalization. At the same time, other mechanisms for travel assistance, educational assistance, development of individualized programs, etc., were established.

R.D. 1276/1982, shows clear values of economic, social, and educational reinsertion and integration. The National Plan for the Toxic Syndrome, on the other hand, shows marked values of political control and organization. Thus, two paths are established that feedback on each other and that will mark, in a decisive way, the definitive management of health in the field of RDs. In this sense, the most social pathway is prior to the National Plan, although after its entry into force, all actions end up being subsumed by this Plan. In fact, the Order of February 15, 1984, which establishes certain measures for the social reinsertion of people affected by toxic syndrome, materializes some beliefs and values present in the R.D. 1276/1982 such as labor promotion and economic autonomy.

In this sense, the Order of February 15 aims to promote cooperatives, labor companies, as well as self-employment. For this purpose, it establishes economic aids. This aspect has a marked labor and educational promotion character. However, we still do not find clear measures that we can determine as strictly social and community measures.

The aforementioned regulations had a high normative importance until the entry into force of R.D. 415/1985, according to which the Ministry of the Presidency was restructured and the competences related to the National Plan for the Toxic Syndrome passed, on the one hand, to the Ministry of Health and Consumption, and, on the other hand, continued in the Ministry of the Presidency. In this case, only the economic and social aspects remain in the Ministry of the Presidency, which implies a greater importance of these aspects as opposed to the biomedical ones. Nevertheless, and in spite of this, this legislative norm means de facto the end of the National Plan for the Toxic Syndrome.

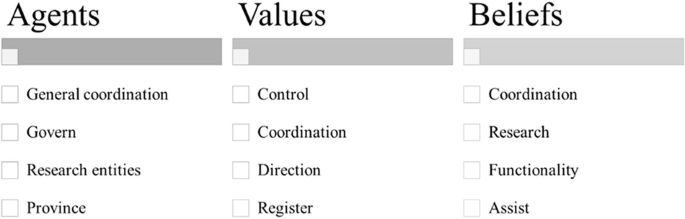

The importance of the social aspect was again emphasized in the Report of the special report on the toxic oil syndrome (Congreso de los diputados, 1995). In it, the social aspects generated by the previous measures (as we indicated before, they also presented this character) are discussed. In the conclusions, it is proposed—(1) to increase coordination, (2) to speed up, the procedures (files and applications) through coordination, (3) to promote and improve collaboration between institutions, and (4) to increase the participation of those affected. This last aspect is noteworthy as it is a political document that clearly establishes the importance of empowering those affected. However, this dialog or participation was not clearly detected in the Spanish regulations of the 20th century, until the impulse promoted by the European institutions. A scheme illustrating all the elements of analysis we are using is shown in image below (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Agents, values and beliefs of Phase IV. Second episode: The institutionalization of rare diseases

Second episode: The institutionalization of rare diseases

The democratization that took place in Europe in the 20th century, and more specifically in Spain, led to major changes in the healthcare system. The SAT tragedy also promoted the acceleration of these modifications. In this sense, the SAT is an outstanding example of how citizen and media pressure promoted political measures. In 1986, the National Health System, was created from the General Health Law, introducing structural changes that affected the approach to RDs, especially in terms of decentralization, research, specialization, primary care, coordination between administrations and the development of early care and diagnosis programs.

The transformation of the Spanish health system was regulated by Law 14/1986, known as the General Health Law. This law was born due to the stagnation of “public organization in the service of healthcare”, as it states. Currently, equity and democratization operate as values which have materialized in the social coverage and health care explicitly present in the preamble of the aforementioned Law. In turn, the value of the patient’s social reintegration is also found as the main motivating element (Art. 6), similar to that established for the SAT phenomenon. This same idea is also found in Article 20 in relation to mental health (another element that is again reminiscent of the rules on EWS). In this sense, the conception of mental health that the norm seems to suggest is broader than the strictly biomedical one, assuming a relationship with the existing social context. This aspect is novel in the political sphere.

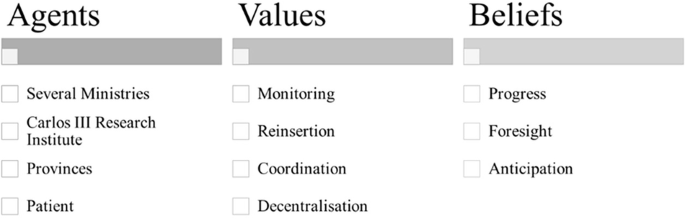

It was necessary to wait 10 years before we could truly speak of a clear process of institutionalization of the social phenomenon of RD. This happened after the enactment of Royal Decree 1893/1996, when the CISAT (Centro de Investigación del Síndrome del Aceite Tóxico) was created within the Carlos III Institute and coordinated by the Subdirección General de Epidemiología e Información Sanitaria (General Subdirectorate of Epidemiology and Health Information). This gave it a certain descriptive and monitoring character of the SAT. This gives the idea that politically it is conceived as an issue that has been overcome and simply needs epidemiological follow-up. After all, what was learned from the EWS was incorporated into the General Health Law of 1986 (Ley 14/1986). This idea of monitoring and evaluation materialized, once again, in the creation of the Interministerial Commission for monitoring measures in favor of people affected by Toxic Syndrome.

This process of institutionalization seems to imply a concentration of resources and control in a single institution, which will be responsible for advancing research and trying to anticipate any problems that may arise. Hence, epidemiological follow-up and health surveillance acquire a hitherto unprecedented importance. In addition, the individualistic paradigm is of great importance, since there is a special focus on the patient, something that was not so marked before (see “Phase III—Economic and social perspective”). A scheme illustrating all the elements of analysis we are using is shown in next image (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Agents, values and beliefs of institutionalization process (Second Episode). Third episode: The European Union as a new intervening actor

Third episode: The European Union as a new intervening actor

The entry of Spain into the European Economic Community (EEC) brought with it the gradual intervention of this institution as an important external agent. This annexation operates as an essential factor to understand the promotion of policies on RDs and national plans within the framework of the EU in the 90’s and in the following years. This fact is very evident in the influence that the decisions of the institutions. The pursuit of coherence and coordination in policies led Spain and other member states to adopt European legislation adopting the national plans to specific regional needs. The year 1999 becomes, at the European level, a special year because of the numerous rules and regulations that were enacted. However, European institutions were aware of the need to address these lesser-known diseases.

The Council of the European Union established the Council Decision of 15 December 1994 adopting a specific program for research and technological development, including demonstration, in the field of biomedicine and health (1994–1998). Article 4.6 of the program indicated the challenges in carrying out fundamental and clinical research on a national scale in the field of RD. In addition, it also indicated that it is possible to develop joint research and experimentation among the member states. It also explicitly promoted the development of an inventory of RDs and the constitution of a bank of “orphan” drugs for clinical research. Once again, the belief in monitoring as a preventive factor was embodied in this regulation. This Decision showed the beginnings of the relevance that RD was going to acquire. So much so that, within 5 years, RD went from being part of an item to having a specific program.

In this regard, Decision No. 1295/1999/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 1999 adopting a program of Community action on RDs within the framework for action in the field of public health (1999–2003). This standard refers to prevalence as a defining element of RDs and to the lack of information on them. Likewise, “RDs are considered to have little impact on society”, which, together with the problems inherent to this type of condition, implies that it is necessary to make progress in understanding them. Another relevant aspect of this decision is the explicit relationship between health, quality of life and community action. Hence, the promotion of a European information network is urged, as well as the promotion of inter-institutional cooperation. With these and other aspects as motivating elements, beliefs and values, the European Parliament creates a specific and innovative Community action program. This program aims to foster cooperation, with a strong community and transnational character, promoting research, as well as relations between health professionals and those affected. We can clearly see that this community action is related to the impact that the EURORDIS association has had since its foundation in 1997. This organization will be crucial in the development of future EU regulations.

Subsequently, on December 16, 1999, the Council of the European Union established a series of incentives for the pharmaceutical industry to develop and market drugs to treat serious and RDs. This Council decision became Regulation (EC) 141/2000, which aims to improve access to treatment, promote research into these drugs and establish European coordination regarding their regulation. According to this regulation, an orphan drug is considered to be as a drug intended to prevent or treat rare or serious diseases which are more common, but making them difficult to market due to the lack of sales prospects. Particularly striking is point two of the previous considerations, where explicit mention is made of patients and of the values of equity in access to treatment. This regulation follows in the footsteps of the standards established in the United States of America in 1983 and, subsequently, in Japan in 1993. Thanks to this regulation, the EU supports the Orphanet initiative, created by the INSERM (French National Institute of Health and Medical Research) in 1997.

On this occasion, we detected a substantial difference between the European and Spanish perspectives. The former emphasizes the importance of the community, whereas the Spanish case, there has been a shift from a social perspective to a more institutional and individual one. A scheme illustrating all the elements of analysis we are using is shown below (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Agents, values and beliefs during the Third Episode.