From a young age, we are taught that rules exist for our own good. Wear a seatbelt. Get vaccinated. Don’t drink and drive. The idea that safety requires legislative intervention, even coercion, is propagated to the public as “tough love.” But where is the line between protection and control? A recently proposed Philadelphia bill tests the law’s bioethical bounds, allowing courts to involuntarily commit individuals suffering from substance abuse. Advocates argue it’s a necessary regulation in a city increasingly overwhelmed by overdoses, while critics contest it’s a blatant violation of medical autonomy disguised as care.

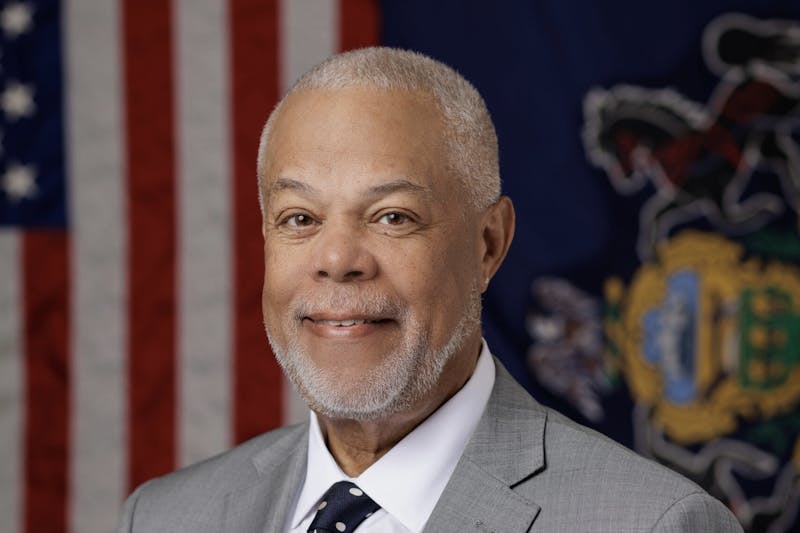

Introduced on May 2 by co–sponsors Pennsylvania state Sens. Daniel Laughlin (R–49) and Anthony H. Williams (D–8), the legislation aims to amend the state’s Mental Health Procedures Act by categorizing substance abuse disorder as a mental illness. The bill would allow law enforcement and officials from the city’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Service to mandate an involuntary psychiatric hold of 120 hours for individuals deemed a danger to themselves or others. Beyond the initial hold, such individuals might also be forced to undergo extended involuntary treatment or compulsory outpatient treatment. The bill has been referred to the Senate Health and Human Services committee and remains under deliberation.

Philly has long been at the center of America’s opioid crisis, with Kensington drawing national attention for its open–air drug markets. In 2022, Philadelphia recorded more than 1,413 overdose deaths, marking the highest total in city history. While the death rate declined in 2023, new drugs such as xylazine threaten to exacerbate the crisis. Despite its recent drop, overdose rates reflect the disproportionate impact of substance abuse on Black and Hispanic Philadelphians. Between 2018 to 2022, overdoses rose by 87% among Black Philadelphians and 43% among Hispanic residents, even as they declined among white residents. For many city officials, the scale of devastation justifies involuntary commitment, yet the bill has garnered criticism for its attempt to resolve decades of systemic failure with force rather than compassion.

Comparatively, critics have questioned the political motivations driving the bill. During the election, Parker campaigned on a platform emphasizing “clean and safe streets,” promising to shut down open–air drug markets in Kensington within her first 100 days in office. In January, she issued an executive order establishing the Kensington Neighborhood Wellness Court which granted police the power to arrest individuals for “quality of life” offenses. The policy targeted drug users, taking them into custody and offering them a choice between court–ordered treatment or a hefty fine. Her support for the bill mirrors broken window policing, indicating a desire to “clean up the streets” rather than invest in community–led solutions.

Supporters frame the bill as a necessary measure to combat rising rates of addiction. Defending the bill against public backlash, Williams released a statement claiming, “It’s a step along the line that would get someone who has been addicted for some period of time an opportunity to get into recovery, even if they were not in their right mind.” However, there is limited research that proves involuntary treatment ensures long–term outcomes. A 2016 report published in the International Journal of Drug Policy analyzed nine quantitative studies involving various modalities of forced interventions, ranging from locked detox programs to group–based outpatient courses. 33% of the studies found no significant benefit of involuntary commitment, while another 22% reported ambiguous or inconclusive results. Retention in coerced programs doesn’t signify sustained recovery.

Research further indicates that involuntary treatment might lead to heightened drug use. Observational data from Massachusetts—one of the few United States jurisdictions with legal civil commitment for substance use disorders—found that individuals subjected to involuntary treatment had twice the rate of fatal overdose compared to those entering voluntarily. Abrupt discharge, reduced opioid tolerance, and inadequate follow–up care all contribute to higher overdose risks. Furthermore, forced rehab in the United States is often conducted in a manner that violates basic human rights, offering little more than court–mandated confinement and abstinence–based programming.

Consequently, harm–reduction networks often advocate for a patient–centered care model where individuals retain their inherent right to dignity and autonomy. Internal motivation—not external pressure—fuels sustained recovery. As a result, individuals are more likely to remain in treatment, engage with therapy, and follow through on long–term behavioral changes.

Nicole O’Donnell, program manager at Penn’s Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy, describes the proposal as deeply flawed. “It’s not evidence based,” she explains. “If we are putting people into treatment that don’t want to be in treatment, it can actually cause overdose … people will [be discharged], and maybe they have been disconnected from their substance of choice for a while, their tolerance decreases, and they overdose the moment they get out.”

Similarly, she warns of the “slippery slope” such policies create: “What’s next? Smoking? Diabetes, if you’re not taking your insulin? It’s a bad policy all the way around.”

Addiction specialists note that the only widely accepted scenario for involuntary treatment occurs when an individual is suicidal, posing an immediate risk of harm to themselves. O’Donnell points out that applying the same logic to substance abuse is misleading because the majority of individuals using drugs do not meet this criteria.

“If we’re talking about people that do suffer from substance use disorder, we’re not talking about patients that are experiencing psychosis from meth or other drugs. That’s a little bit different,” she says. “People with opiate use disorder or fentanyl addiction are usually stable enough to make decisions. While the choices aren’t great, they’re not incapacitated to the point where they can’t decide for themselves.”

Jeanmarie Peronne, an emergency medicine physician and addiction specialist at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, echoes this sentiment, framing the bill as a bioethical breach.

“In general, we let patients decide if they want to be put on a ventilator, even though they might die,” Perrone says. “And this is a similar scenario where we really trust that patients know what’s best for themselves, and that, in the absence of their own motivation to address their substance use, forcing them is not going to be successful.”

For decades, harm reduction advocates have worked to replace dehumanizing punishment with evidence–based treatment; however, critics fear that the bill could undo years of progress.

In a statement to Axios, Executive Director of PA Harm Reduction Carla Sofronski criticized the proposal’s pending implementation: “Treating addiction like a criminal or psychiatric issue—rather than a public health concern—perpetuates stigma and ignores the evidence that harm–reduction strategies are most effective at saving lives.”

Another significant concern is further eroding the tenuous line of trust between vulnerable populations and medical professionals. “People will be afraid to seek help,” O’Donnell says. “I’d be afraid that in the emergency room, people won’t ask for help … because they’re afraid that we’re just going to involuntarily commit them.”

Similar patterns are often seen in mental health crises, where fear of involuntary psychiatric holds deter individuals from accessing critical care. Black and Hispanic Philadelphians, who have historically borne the brunt of punitive drug policies, may be especially wary. Forced treatment could adversely deepen pre–existing divides, driving individuals away from voluntary services proven to reduce overdose deaths, such as medication–assisted treatment and harm reduction programs.

Additionally, critics have attacked the structural viability of the bill, pointing out that its implementation would be costly and complex. Philadelphia’s treatment centers are increasingly stretched thin and residential treatment beds are limited. “The treatment care centers aren’t really equipped to have people there that don’t want to be there,” O’Donnell said. “Where would we put everybody?”

Implementing the bill into existing medical centers would require secure facilities, increased staffing, and longer hospital stays, presenting expensive and logistical challenges that lawmakers have yet to expound upon.

Beyond its dubious logistical feasibility, the bill may detract resources from developing compassionate approaches to care. Contrary to coercion, evidence has shown that expanding access to medication for opioid use disorder, such as methadone, consistently reduces mortality by more than 50%. Similarly, peer recovery programs, housing–first initiatives, and harm reduction services (e.g. syringe exchanges, overdose prevention centers, etc.) offer alternative methods of evidence–based treatment.

The United States has already seen progress from these approaches. The slight drop in overdose deaths in 2023 is attributed in part to increased Narcan distribution and other forms of community–based outreach. Critics argue that scaling these efforts, rather than imposing involuntary treatment, would effectively combat Philly’s drug crisis without compromising individuals’ medical autonomy.

The debate over Philly’s involuntary treatment bill reflects the country’s broader discourse on combatting its overdose epidemic. The outcome of the bill could set a precedent across the country for how cities should respond to mounting addiction crises.

For a city facing increasing pressure to “solve” its drug crisis, the appeal of hard paternalism is understandable. Yet, as decades of failed punitive approaches have shown, the desire to find quick fixes does not justify stripping individuals of bodily autonomy. Like anti–tobacco campaigns and age–restricted alcohol consumption, addiction policy must balance safety with agency. While voluntary, low–barrier treatment empowers individuals to regain control of their health, involuntary commitment risks higher overdose rates, reinforces stigmas, and jeopardizes long–term recovery. Ultimately, the bill presses the city to decide whether it is fastening a seatbelt—or seizing the wheel.