Imagine this: A patient codes in the hospital. The medical team rushes in, performing CPR, administering medications, and making split-second decisions that can mean life or death. Now, imagine if those same medical professionals could hit “reset,” step back, and try again — this time with the benefit of hindsight and guidance, free from real-world stakes.

This is not science fiction. It’s a weekly reality at TCU’s Burnett School of Medicine, where simulation technology has become a core part of the curriculum. Here, students don’t just study medicine — they live it, in a high-tech environment that lets them make mistakes, learn, and try again without risking patient safety.

The Burnett School’s distinctive Empathetic Scholar® curriculum (yes, it’s trademarked) integrates this simulation training seamlessly into medical education. According to Adam Jennings, D.O., executive director of Simulation, Innovation, and Research, the program aims to model its educational philosophy after the adult learner — moving beyond passive lectures toward active, hands-on experiences.

“The whole purpose,” Jennings explains, “is to transform the way that we’ve classically taught med school to something that’s not just more impactful, but easier for students to grasp in the moment.”

Unlike many traditional medical schools, where students don’t often see patients until their third or fourth year, TCU students begin clinical rotations right away, during Phase 2 of their training. They spend most of their weeks embedded in hospitals and clinics across the region, from Cook Children’s to Baylor Scott & White, gaining real-world experience in family medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine, surgery, and more.

But once a week — every Thursday afternoon — all Phase 2 students come back to campus for LEAPS: Learning and Pondering Sessions. These classes focus on simulation and technology training, reinforcing the skills they practice in clinical rotations with immersive, scenario-based exercises.

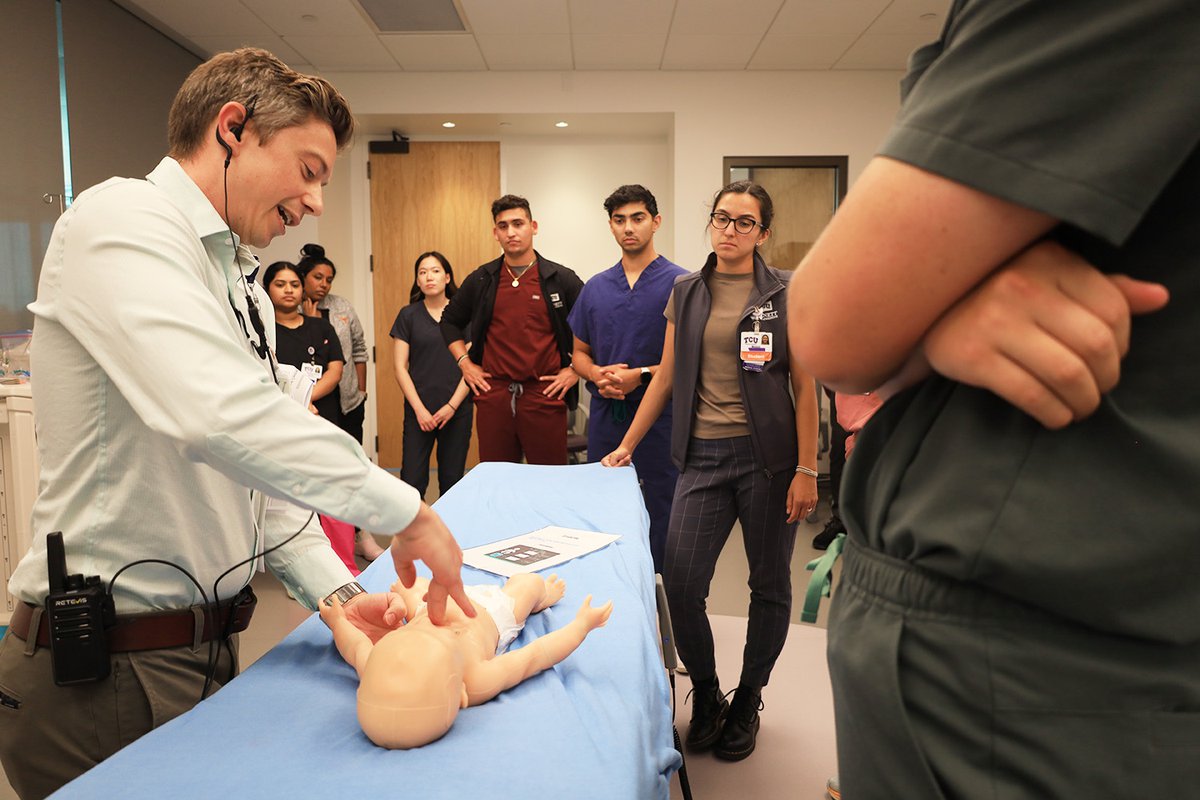

During one of these LEAPS sessions, where students split into small groups to tackle cases ranging from pediatric respiratory distress to adult cardiac arrest, Fort Worth Magazine had a firsthand look. One session used rapid cycle deliberate practice — students performed CPR on high-fidelity mannequins, and when errors occurred, instructors paused to provide guidance, then switched groups to restart the scenario from the beginning and see how they handled it. It’s the kind of practice the school believes in: deliberate, hands-on, and repeated until mastery.

“The theory here is practice isn’t what makes perfect — perfect practice makes perfect,” said Chinmay Patel, D.O., emergency medicine clerkship director at the Burnett School of Medicine. “They don’t just hear about what to do. They actually do it, make mistakes, get coached, and try again — all in a safe environment.”

Students also engage with augmented reality and virtual lenses to visualize anatomy during stroke simulations, bridging the gap between textbook knowledge and clinical reality. These tools aren’t just bells and whistles — they’re carefully integrated to accelerate learning and boost retention.

But learning simulation extends beyond clinical scenarios to the emotional demands of medicine. One powerful example comes during the Transition to Residency course, a two-week capstone before graduation. Students face a heartbreaking case: a maternal death that can’t be prevented. After attempting resuscitation, they must then deliver the devastating news to the patient’s husband — played by a trained actor.

This exercise trains students not only in medical decision-making but also in empathy and communication — the core of the Empathetic Scholar model. “Delivering bad news is not something that’s traditionally taught in med school,” Jennings said. “Most physicians learn it on the job. Here, we teach it. We focus on tone, body language, and what information to share — making sure they practice empathy, not just medicine.”

While other medical schools are beginning to incorporate simulation, TCU’s approach is unusual in how deeply and consistently it’s embedded throughout the curriculum.

“[The] first time you do these things on a real patient should not be the first time you’re doing it ever,” Jennings said. “We want to make sure our students and their patients are set up for success.”

Third-year student Nico Martinez describes how these sessions give him a reality check beyond textbook learning. “It’s one thing to learn about CPR or resuscitation methods in a book. We all have our own images of what it looks or feels like — adrenaline rush — chaos,” he says. “But what they’re really trying to recreate is the madness behind the scenes, the algorithms, the processing happening in that short amount of time, and the teamwork it requires.”

Martinez pushes back on the myth of the heroic lone doctor, the “all-omniscient” figure who knows and does it all. “It’s a team. Without simulating or being in these environments, you don’t know what it feels like. You can know everything like the back of your hand from a book, but that doesn’t mean you know how to work within a team, how to collaborate, or establish roles. In those awkward moments when you feel dumb and don’t know what’s going on, that’s when you have to remember your team. ‘What do you know? What do you remember?’”

Angel Sheu, also a third-year student at TCU, echoes Martinez’s perspective, highlighting the value of repetition and real-time feedback. “It was an amazing experience,” Sheu said. “We got to do it over and over, from bottom to top, top to bottom, and reverse — just running through all of that so that when we’re in a moment and panicked, we can rely on that muscle memory.”

Sheu points out how the students became noticeably more efficient during the session. “By the end, we were going faster. Simulating that high-stress environment and getting immediate feedback was really cool. We saw a patient in distress, gave treatment, and watched how those numbers changed. It helped simulate a real-world environment.”

Jennings notes that when he went to medical school, simulation technology like this simply didn’t exist. “We did not have all this computerized technology, augmented reality, virtual reality. Our approach was very different. Usually, you don’t make decisions until you graduate. Here, students are making clinical decisions early, in an environment where it’s okay to be wrong.”

This early exposure is designed to help students avoid the shock of transitioning from classroom theory to real-life medicine. Jennings recalls his own experience as a newly minted doctor, feeling overwhelmed by the responsibility of real patients.

“It took me until my second year of residency to really feel like I could put it all together. Because of the way we’re modeling education here, I think our students will be at least a year ahead.”