On Thursday, as the calls for tax reform continued to pile up, the prime minister went further: “The only tax policy that we’re implementing is the one that we took to the election.” Of course, there are many areas of potential reform beyond tax. But, on the face of it, tax reform is now a dead letter in this term of parliament. Strike two.

Tension between the treasurer and the prime minister appeared to emerge. Chalmers seemed ambitious for big change; Albanese seemed reluctant.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Treasurer Jim Chalmers. “Their differing appetites for reform are a natural outgrowth of their jobs.”Credit: Alex Ellinghausen

Now Chalmers has issued his own cautionary guidance. Facing an expectation that the invited members of the roundtable would emerge with a list of reform decisions at the end of the three-day discussion in Parliament House on August 21, Chalmers tells me: “The roundtable is not about making decisions. It’s about informing them.”

And, facing an expectation that it would produce a work list for rapid reforms, he says: “It’s helping us build a substantial agenda over the course of the next two budgets.” For the next two years, not the next two months.

The group of officials, business leaders, policy wonks, union chiefs, tech experts, shadow treasurer Ted O’Brien, farmers, miners and big investors will not issue a communiqué. There will be no show of hands in the cabinet room, no voting on specific measures. Sounds like reform is being put on the never-never. Is this strike three and out?

No one has yet been sent to any labour camps in this corrective campaign. Yet there are two distinct Labor camps.

The tension between Albanese and Chalmers is real. Their differing appetites for reform are a natural outgrowth of their jobs. The prime minister is responsible for winning not only the last election but the next; the treasurer is judged by the health of the economy.

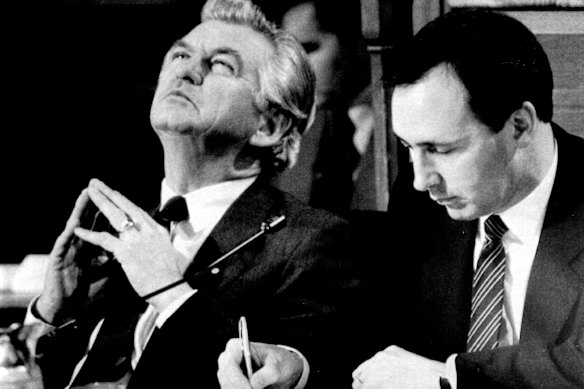

This tension is familiar. Bob Hawke and Paul Keating. John Howard and Peter Costello. These were winning partnerships that produced successful, reforming governments.

Up to a point. That point is where a treasurer’s personal ambition begins to intrude on the working relationship. In the end, Keating’s ambition destroyed Hawke. It ended the reform partnership. Costello’s ambition unsettled the Howard government but, less overweening, it did not destroy it.

What is the character of Albanese’s relationship with Chalmers? Will it be destructive or co-operative?

The older man, 62, from the NSW Left faction of Labor, is dominant, no question. His priority is not economic reform but political trust.

Bob Hawke and Paul Keating had a winning partnership, but ultimately, Keating’s ambition destroyed Hawke.

Albanese is acutely conscious that trust in government has fallen worldwide. That Labor was re-elected with a big majority but a relatively poor primary vote of just 35 per cent. That, if he wants to keep winning elections, he has to build trust. That means delivering on the promises he made in the campaign.

“Our government is focused on delivery,” Albanese told the National Press Club after the May election, not only because it would improve people’s lives, he said, but because “it also matters for our democracy”. Keeping promises restores faith in government and builds trust. Trust builds support. Support wins elections.

Albanese also explained his cautious approach to reform: “The way we make change, the ‘how’ matters. Because change that is imposed unilaterally by government rarely endures. Key to lasting change is reform that Australians own and understand.” In other words, he wants to bring the people with him. No sudden moves.

How could he possibly win an election largely fought on the cost of living and then turn around and impose a bigger GST, for instance? It would be a shattering breach of faith. And an invitation to political suicide.

Besides, there’s a very practical problem with a bigger GST. The way it’s constructed, all the revenue goes straight to the states. The federal government would not be able to use any increase in the tax take to cut other taxes, or compensate low-income people, unless the states – all of them – agreed to it. That would be hard, verging on impossible.

After a second election win even bigger than his first, Albanese is working towards a third. He’s invigorated by the job, by his success, and by the extraordinary discipline of his government. He sees no reason why he can’t rival Hawke’s run of nearly nine years.

The younger man, 47, from the Queensland Right faction, has been respectful and disciplined. He’s also emerged as the frontrunner to succeed Albanese. He’s patient. He said of Albanese on election night: “My expectation and my hope is that he serves a full term and runs again.”

Abjuring personal ambition, he says he’d be “very happy” to remain as treasurer for the life of the Labor government.

Loading

But while he can afford to wait, he can’t afford to sit on his hands. He’s acutely aware of Australia’s falling living standards. He’s acutely aware that it’s his job to address the problem. Besides, he knows that he’s constantly measured against Keating’s reforming treasurership. And that his credentials to succeed Albanese will depend largely on his reform efforts.

The only big disagreement between prime minister and treasurer in their first term was over the so-called stage three tax cuts that Scott Morrison had bequeathed them. Chalmers was keen to redesign them, taking some of the benefit from the rich to give to the rest.

Albanese, reluctant to break his promise to keep them intact, resisted. Until he eventually agreed that it was a risk worth taking amid a cost-of-living crisis.

Do the two men differ on any of the big reform questions of today? Yes, they do. While they’re both busy today trying to downplay expectations of the roundtable to come, they have divergent views on the vexed question of negative gearing.

Loading

The two are playing to character. Albanese is opposed to revising this tax concession for property investors. And for good reason. Bill Shorten proposed to curb it. He was smashed at the 2019 election. It was not the sole reason that Labor lost that election – Bill Shorten was another reason that Bill Shorten lost. But it was a contributing factor.

Yet Chalmers has a different view. Negative gearing, while sacrosanct to many older voters, is seen as an affront to younger ones. It’s become an emblem of what Ken Henry calls the “intergenerational bastardry” of Australia, leaving the next generation worse off. Older people are seen to be gathering up all the available real estate as tax dodges while leaving nothing affordable for their youngers.

Chalmers would like to address this as evidence of good faith with the next generation. It would be opposed vociferously. This difference of opinion between leader and treasurer will remain behind closed doors, worked out over the months and years ahead. So no change to negative gearing will emerge from the roundtable.

The main area of reform to be embraced in 10 days’ time is set to be deregulation. For business, to spur investment, to aid growth, and to help with house building. This is low risk for Labor and zero cost to the budget. The Albanese government will remain disciplined. No rectification campaign necessary.

Peter Hartcher is political editor.

Get a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up for our Opinion newsletter.