Dutton

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

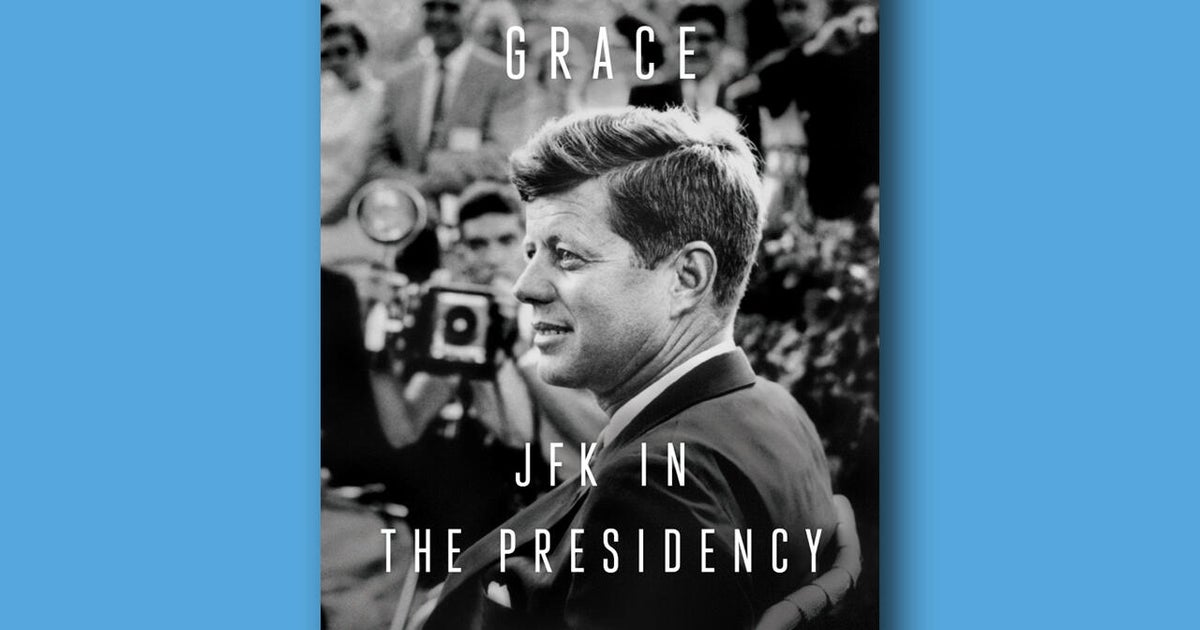

“Incomparable Grace: JFK in the Presidency” (Dutton), by presidential historian Mark K. Updegrove, traces John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s years in the White House, including his final days leading up to a political fundraising trip in Texas.

Read an excerpt below, and don’t miss Erin Moriarty’s interview with Updegrove on “CBS Sunday Morning” August 10!

“Incomparable Grace: JFK in the Presidency” by Mark K. Updegrove

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

Dallas

Occasionally, John Kennedy would consider what he would do after his presidency. “Oh, probably sell real estate,” he once joked when asked about it. “That’s the only thing I’m equipped to do.” Perhaps half-kiddingly, he suggested to Ben Bradlee that the two of them should buy the Washington Post. In more serious moments he mentioned becoming the president of Harvard or running for the Senate. Jackie suspected that she and her husband would have lived between Cambridge and New York, and that he would have occupied his time in the immediate years after leaving office by writing a book, planning his presidential library, and traveling the world, playing the role of “President of the West,” an international celebrity and sage voice on the issues of the day.

After two terms, JFK would have been a relatively youthful 51-years-old, making him the youngest former president since Theodore Roosevelt stepped down in 1909 at age 50—only to find himself restively pining away for the office he had willingly given up. Hungering to get back into the arena, TR made an unsuccessful bid for the presidency in 1912. Perhaps anticipating the same kind of middle-aged restlessness and longing for lost power from her husband, Jackie told him she wished “they made a rule that would keep you here forever.” “Oh, no,” Kennedy said, “eight years is enough of this place.”

But it was clear to anyone around him that he loved every second of the job, and he intended to keep it until his two terms were up—and that would require earning reelection the following year. To that end, in the late afternoon of November 13, just under a year before Americans would go to the polls, Kennedy convened Bobby, brother-in-law Steve Smith, Kenny O’Donnell, Ted Sorenson, Larry O’Brien, DNC chairman John Bailey, party treasurer Richard McGuire, and director of the Census Bureau and political strategist Richard Scammon to begin formally taking aim at the challenges that lie ahead in the 1964 election. For over three hours the group met in the Cabinet Room. As they discussed Kennedy’s prospects, a general feeling of optimism pervaded.

There was reason to be bullish. The economy was humming along, with the gross national product up $100 billion over 1960, Eisenhower’s last year in office. The Soviets, humbled by the Cuban Missile Crisis a year earlier, remained in check as the superpowers enjoyed a period of détente, while in Houston NASA was developing a Saturn I rocket that, if successfully launched, would be the most powerful to date, paving the way for the U.S. to leapfrog past the U.S.S.R. in the space race. Plus, Kennedy’s approval rating stood at a hardy 59 percent, with national polls reflecting that he was the most admired man in the world, ahead of beloved figures like Eisenhower, Churchill, and renowned evangelist Billy Graham.

At age forty-six, flecks of gray in his thick sheaf of chestnut hair, Kennedy stood astride the world stage nonpareil. “Let’s face it, after these many months into his office, JFK is no ordinary chief magistrate,” gushed William Styron in an Esquire profile published in September 1963, “but the glamorous and gorgeous avatar of American power at the magic moment of its absolute twentieth-century ascendancy. The entire world, including even the Russians, has gone a little gaga over this youthful demigod and his bewitching consort and [this] writer has to confess that he is perhaps a touch gaga himself.”

Just as encouraging were Gallup polls that matched up Kennedy against prospective Republican rivals Barry Goldwater, Nelson Rockefeller, and George Romney that, in each case, gave Kennedy a double-digit edge. Of the three, Kennedy had feared Rockefeller the most. He believed that had the New York governor entered the primaries in 1960, he would have gotten the GOP nomination and beaten him in the general election. But by 1963, Rockefeller had divorced his wife and married a younger woman, also a divorcee, diminishing his popular appeal on moral grounds.

George Romney, the governor of Michigan, was also seen as a threat. The devout, clean-living Mormon hadn’t yet announced his intentions to run for the presidency as he waited for a sign from God. Bobby believed conservatives and moderates alike might “fall for that God and country stuff.”

Given his druthers, Kennedy would have chosen Goldwater as his Republican challenger. The preeminent conservative of the day, the senator from Arizona was seen by many, including moderates in his own party, to be an extremist who lacked the temperament to be president in the nuclear age. The impression was reinforced by statements that were considered outrageous by the standards of the early-1960s, including Goldwater’s suggestion to drop “a low-yield atomic bomb on the Chinese supply lines in Vietnam,” and, rather than sending a space craft to the moon, lobbing “one into the men’s room of the Kremlin.” They helped to explain a March 1963 poll that had Kennedy winning over Goldwater by a margin of 67 to 27 percent, with 74 percent expecting that Kennedy would be reelected. For Kennedy, a face-off with Goldwater would have been too good to be true.

Still, regardless of his opponent, Kennedy’s reelection would by no means be a fait accompli. Kennedy himself was keenly aware of the capricious nature of politics and talked repeatedly about how “tough” the campaign would be. He had seen a steady rise in his disapproval rating, which now stood near 30 percent, with the increase correlating directly with his push on the controversial civil rights bill. In November, he acknowledged the decline in his popularity as a consequence of his stand. “Change always disturbs,” he said, “and therefore, I was surprised that there wasn’t greater opposition.” But it irked him that the civil rights bill, along with a tax relief bill he had proposed to stave off a possible recession the following year, had stalled in Congress with no immediate prospects for resuscitation. “The fact of the matter is that both of these bills should be passed,” he groused. The president’s legislative impotence—Medicare and other bills had also been stymied—became another cause for worry as the Kennedy team looked toward 1964. But all things considered, Kennedy was riding high.

Absent from Kennedy’s reelection strategy session, perhaps conspicuously, was Lyndon Johnson. By the fall of 1963, rumors swirled across Washington that Kennedy would drop LBJ from the ticket—speculation that was quickly struck down by the president himself. Sensitive to how Johnson might respond as the gossip inevitably made its way to him, Kennedy told Johnson’s aide Bobby Baker, “I know he’s unhappy in the vice presidency. It’s…the worst f***ing job I can imagine… What I want you to do is tell Lyndon that I appreciate him as vice president. I know he’s got a tough role and I’m sympathetic.” Alluding to the hearsay and invoking the words of FDR, Kennedy instructed Baker to assure Johnson that he had “nothing to fear but fear itself.” When Charlie Bartlett brought up the rumor during a skinny-dip in the White House pool, Kennedy impatiently snapped, “Why would I do a thing like that? That would be absolutely crazy. It would tear up the relationship and hurt me in Texas. That would be the most foolish thing I could do.”

Indeed, Texas was on Kennedy’s mind in November as the White House planned a two-day, five-city presidential visit throughout the state the week before Thanksgiving. Conventional wisdom has it that Kennedy wanted the trip to mend political fences. As civil rights had come to the fore, heavily Democratic Texas had experienced a split in the party ranks, with Texas governor John Connally heading up the conservative wing and the liberal faction led up by Senator Ralph Yarborough. Though Yarborough’s progressivism was closely aligned with Johnson’s, they, too, had a fractious relationship due to the vice president’s association with Connally, a close friend and former aide. The story goes that Kennedy had hoped to use the trip to bring the two sides together in the interest of party harmony. Both Johnson and Connally would later dispute that notion. “Hell,” Johnson said, “if he wanted to bring us together, he could have done that in Washington.”

In fact, the trip was mostly about money. As he geared up for 1964, Kennedy saw an opportunity to lean on Johnson and Connally to put the arm on wealthy Texas Democrats, many of whom opposed Kennedy, to support an Austin fundraiser that would add a million dollars to the campaign war chest—a huge sum at the time—and would jump-start the reelection effort. Getting Texans to step up would also be a loyalty test for Johnson, especially as rumors that he would be dropped from the ticket hung in the air.

Connally opposed the trip due to the president’s declining popularity in the state, which had seen a drop in Kennedy’s approval rating from 76 percent to 50 since the beginning of the year due largely to Kennedy’s stand on civil rights. Instead, Connally recommended that the president come in the beginning of the next calendar year in order to let things settle a bit. But when the Kennedy camp pushed for the trip in the fall of 1963, Connally pressed them to make it not just the fundraiser in Austin, but a two-day swing through the biggest cities in the state, which the Kennedy-Johnson ticket had won in 1960 by a scant two percentage points. Kennedy got his fundraiser, Connally got the president’s commitment to a visit that would include stops in Houston and San Antonio on one day and Fort Worth, Dallas, and Austin the next.

On the morning of Friday, November 22, John Kennedy was awakened in suite 850 of the Texas Hotel in Fort Worth with a gentle rap on the door from George Thomas, who had traveled to Texas with him and the first lady. Thomas informed him that it was raining outside, but as Kennedy made his way to the window, he would find that it hadn’t discouraged locals from turning out to greet him.

The trip to Texas marked the first public outing for Jackie with her husband since losing Patrick three and a half months earlier. As ever, she proved to be a big draw, though she declined to participate in the first event of the day, a hastily arranged speech in the parking lot outside the hotel. Originally slated for 8:45 am, the event was rescheduled to mid-morning, then pulled back to 8:45 again due to the president’s concerns that those in the audience would be late to work. “There are no faint hearts here in Fort Worth,” he said to some 3,000 who braved the drizzle, “and I appreciate your being here this morning. Mrs. Kennedy is organizing herself. It takes her longer, but, of course, she looks better than we do when she does it.”

When the first lady appeared for a breakfast with the heavily Republican Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce later that morning—dressed in a light pink wool Chanel suit with navy blue trim, a matching pill box hat, and white gloves—she did not disappoint. “Two years ago, I introduced myself in Paris by saying that I was the man who had accompanied Mrs. Kennedy to Paris,” Kennedy said to the delight of the audience, his pride in his wife palpable. “I am getting somewhat the same sensation as I travel through Texas. Nobody wonders what Lyndon and I wear.” Reporters surveying those who had come out to see President and Mrs. Kennedy throughout the state would find that at least half, women and men alike, had come to see her.

It was to be a busy day for the Kennedys, as well as for Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson and Connally and his wife, Nellie, who acted as hosts, accompanying the first couple throughout their trip. After breakfast they would take a short hop to Dallas, where the Kennedys would travel by motorcade to the Trade Mart for a luncheon. Then it would be on to Austin for a major fundraising dinner arranged by Governor Connally before spending the night at the vice president’s LBJ Ranch seventy miles away in the heart of Texas Hill Country.

There was some trepidation about the first stop. Dallas was not known for its civility—at least to those considered liberals by local fringe Republicans. A month before Kennedy’s visit, Adlai Stevenson had given an address at Dallas’ Memorial Auditorium Theater and was accosted afterward by jeering anti-U.N. extremists. A woman hit him over the head with a placard that read “Down with the U.N.” and a young man spat on him as he walked to his car—then, for good measure, spat on the cop who moved in to arrest him. “Dallas has been disgraced,” the Dallas Morning News wrote in a page one editorial the following day. “There is no other way to view the storm-trooper actions of last night’s frightening attack on Adlai Stevenson.” Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson were met by similar invective three years earlier. Just prior to the election in 1960, they were besieged outside the Adolphus Hotel by protesters carrying signs that read “Lyndon Go Home,” and “Let’s Ground Lady Bird.” As they crossed the street, they, too, were spat upon.

On the day of his visit, the John Birch Society welcomed Kennedy with an ad in the Dallas Morning News accusing him and Bobby of being “soft on Communists, fellow-travelers and ultra-leftists.” Kennedy ran across it as he examined the newspapers that morning. “We’re heading into nut country today,” he told his wife as they prepared for the day. “But, Jackie, if somebody wants to shoot me from a window with a rifle, nobody can stop it, so why worry about it?”

But the visit to Dallas looked promising before it even started; autumn rain clouds turned to boundless blue sky during the Kennedys’ thirteen-minute flight to Love Field, where Air Force One touched down at 11:38 am. As they disembarked, Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson awaited them along with a few thousand well-wishers pressed along the fence line beyond the tarmac. The Kennedys spent a few minutes greeting some of them, one of whom presented Jackie a bouquet of a dozen red roses, before they slipped into the plush back seat of the presidential limousine—a 1961 Lincoln Continental, midnight blue gleaming in the North Texas sunshine—that would carry them and John and Nellie Connally to the Trade Mart. The fortuitous change in weather prompted Kennedy to order that the limousine’s clear plastic bubble top be removed and its bulletproof windows rolled down.

A hundred and fifty thousand people lined up along the ten-mile motorcade route, swelling to as much as twenty or thirty deep, as the car neared downtown, “absorbed,” as one Texas reporter wrote, “in the power and glory of the moment; in this their touch with the fabulous.” The first couple glided before them, smiling and waving as they passed, enjoying it all. The crowd was a snapshot of America in its time, mostly white with pockets of black and brown; housewives and young working women in office garb; men in business suits, others in open collars and hard hats; handfuls of students; small children on the shoulders of their fathers, or holding the hands of their mothers with one hand as they held tiny American flags in the other. As the car approached, cheers rose and patches of confetti rained from buildings. “You can’t say that Dallas isn’t friendly to you today,” Nellie Connally said to the president at 12:30 p.m. as the car rounded the curve of Main Street to move toward the highway overpass.

Then came the crackle of gunfire. Three shots in quick succession echoed from the dull red-brick Texas School Book Depository Building across Dealey Plaza. The president was propelled forward by a bullet that hit above his right shoulder, passing through his lower neck, his balled-up fists rushing reflexively toward the wound. He sprung back upright before he was thrust forward again by another shot to the back of his head, which fell to Jackie Kennedy’s lap as his body collapsed. “Jack!” the first lady cried out, “Oh, no! No!” Fear and disorder reigned in an instant. Horrified onlookers watched the car race off to Parkland Hospital, just over three miles away.

It arrived at 12:35. Kennedy was stripped of his jacket, shirt and t-shirt and rushed into Trauma Room One. Malcolm Perry, the 34-year-old doctor on duty, was summoned from lunch in the hospital’s main dining room with an emergency page, arriving in short order. Kennedy wasn’t breathing. Blood from the gunshot wounds on the back of his head and neck fell to the floor. Perry ordered a nurse to get three of the other Parkland doctors right away. He gave Kennedy a tracheotomy, then a blood transfusion. Doctors and nurses burst in and out of the small, gray tile room. The hospital’s chief neurosurgeon in residency, William Kemp Clark, entered. Before aiding the other doctors, he approached the first lady, who stood silently to the side, her husband’s blood caked on her pink skirt.

“Would you like to leave, ma’am?” he asked her gently. “We can make you more comfortable outside.”

“No,” she said. Motionless, she remained by his side to the last, her eyes never leaving his. She didn’t cry as the doctors fought to save his life, forcefully pumping his chest to bring breath back into his limp body. She didn’t cry as they stopped after ten minutes and pulled a white sheet over his head at 1:00 p.m. Central Standard Time, half an hour after the shots were fired, nor when a 70-year-old priest was brought in to give the patient his last rites, rubbing holy oil in the shape of a cross on his forehead. She held her emotions at bay as she stood placidly before him for the last time and took his wedding ring from his finger, replacing it with hers and whispering into his ear words long left to eternity.

Reports soon went out on the news wires: John Fitzgerald Kennedy was dead.

Left unsaid were the words the thirty-fifth president had planned to use to conclude the speech he was to give in Austin that same evening:

Let us stand together with renewed confidence in our cause—unified in our heritage of the past and our hopes for the future—and determined that this land we love shall lead all mankind into new frontiers of peace and abundance.

From “Incomparable Grace.” Reprinted by arrangement with Dutton, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, a Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © Mark K. Updegrove, 2022.

Get the book here:

“Incomparable Grace: JFK in the Presidency” by Mark K. Updegrove

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info: