How very weird to return to this old manuscript, the scene of so much doubt and anguish, not to say obsession.

I was a baby when the seed was planted, three years out of school, two years since my devastating failure in the first year of a science degree. I had drifted into advertising where the gods determined I would fall among novelists and playwrights who would lead me to a place I could never have imagined.

My most important workmate was a former schoolteacher, 32 years old, the father of six children, but an apprentice just as I was, still waiting for the day when his copy would be accepted by our boss. I drove Barry Oakley to work. He gave me Kerouac’s Lonesome Traveler and other books he had reviewed, made sure that I saw Chekhov and Beckett and Ionesco, accompanied me to the first two art exhibitions of my life.

Sidney Nolan’s paintings of Ned Kelly left an indelible mark on a young Carey. Photograph: State Library Victoria

It was lunchtime at the office when we boarded the tram to see The Ned Kelly Paintings 1946–47: Sidney Nolan at George’s art gallery. I had no expectation of anything except the egg and lettuce sandwich waiting for me back at work, no idea that Nolan’s Kelly paintings were about to burn into my brain and leave their mark for ever.

It was 1963 and to quote One Hundred Years of Solitude, “the world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point”. It was the year I discovered Ornette Coleman and Ingmar Bergman, Robbe-Grillet, Bob Dylan, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. I stumbled into James Joyce’s Ulysses and – ignorant as I may have been – recognised a holy place, a blasphemous cathedral which had been banned, unbanned, banned again.

These ecstatic moments are denied the old and wise, reserved for the very young who turn the pages of Ulysses and who can hardly believe that such a string of words exists:

I cant help it if Im young still can I its a wonder Im not an old shrivelled hag before my time living with him so cold never embracing me except sometimes when hes asleep the wrong end of me not knowing I suppose who he has any man thatd kiss a womans bottom.

Are you allowed to say that?

Carey in 1964. Photograph: Maggie Diaz/State Library Victoria

It was the year I read Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and “saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked”. I sought out Max Brown’s Australian Son: The Story of Ned Kelly and it was here I found that Ned Kelly had also been a writer tortured by the cruelties of the British law. There were 56 pages and in every one he was on fire, enraged, breathless, a widow’s son outlawed.

Dear God, I thought, has no one ever really understood what Ned wrote before he robbed the bank at Jerilderie? Did no one see what I saw – that our famous bushranger was a raging poet?

my mother and four or five men lagged innocent, and is my brothers and sisters and my mother not to be pitied also who has no alternative only to put up with the brutal and cowardly conduct of a parcel of big ugly, fat necked, wombat headed, big bellied, magpie legged, narrow hipped splay-footed sons of Irish bailiffs or English landlords which is better known as officers of justice or Victorian police who some calls honest gentlemen (Ned Kelly – The Jerilderie Letter)

I transcribed the letter and carried it on my person like the relic of a martyred saint. I knew (if no one else did) that I would be a writer and I would know how to do something with this letter when the time arrived. In 1964 I wrote my first unpublishable novel. In 1966 I tried again. So it went. Attempts. Failures. Sweet dreams and flying machines in pieces on the ground. By 1974, when I finally became airborne, I had lost the Jerilderie Letter.

Years passed. Three lives later I was living in New York City. It was 1993 and the Metropolitan Museum of Art was exhibiting the same Kelly paintings I had seen 30 years before. If I did not rush to see them it was because I was certain they could never dazzle the man as they had the callow boy.

A document about Ned Kelly from Victoria police circa 1874. Photograph: State Library Victoria

But my friend the Vassar professor was acting as a docent for the exhibition, and it was he who finally persuaded me to visit and then – dear Jesus – what wonders. I was amazed and proud, of us, of Ned, of Nolan, and I began taking my downtown friends uptown see the show. And as I circled the rooms telling the strange story to my victims, it struck me: I was going to write this bloody novel after all.

Why write about Ned Kelly, said my old Sydney friend. We know all about him.

And yes, we knew the police reports and the court transcripts. We knew the Land Acts and the day Ned fought Wild Wright. We knew Jerilderie, Euroa, Stringybark Creek and Constable Fitzpatrick. We knew the history all the way to the execution in Melbourne jail.

But you cannot know a boy’s soul from a police report. And Ned Kelly was a boy for most of his short life, and we – having the image of the bearded outlaw in our mind – hadn’t spared a thought for that smooth-cheeked boy who loved his mother, lost his father to police, was apprenticed to a bushranger named Harry Power.

Photographs and notes from Carey’s research materials while writing True History of the Kelly Gang. Photograph: State Library Victoria

I raided Ian Jones’ Ned Kelly to find my story’s spine but I also read obsessively around the subject. I visited Eleven Mile Creek, Benalla, Stringybark Creek, Greta, the first time with my dear friend Paul Priday and Sam, my 11-year-old son, the second time with the architect Richard Leplastrier and publisher Laurie Muller. Laurie was a horseman. Laurie taught me the landscape from a horseman’s point of view, forced me to climb hills I would rather have ignored, sleep out in a swag on a rainy night when, honestly, I preferred a motel bed. The three of us visited Powers Lookout while hungover from duty-free Laphroaig, but not even alcohol poisoning could diminish Leplastrier’s supreme visual intelligence. I made notes, saved a leaf at Stringybark Creek, composed an encyclopedia of smells.

The book that finally emerged owes so much to Richard and Laurie, but also to my first 10 years of life in Bacchus Marsh, one hour’s drive from Beveridge where Ned was born. It was just 60 years since Ned’s departure when I arrived and you could hear the language of Ned’s letter in the playground of State School #28.

Carey’s notebook shows the author mapping out the chapters in True History of the Kelly Gang. Photograph: State Library Victoria

And it was that language that made me want to write True History of the Kelly Gang, to make a modern poetry from the voice of a hero who was condemned to death by the founder of State Library Victoria, the same institution that now holds his Jerilderie Letter, his armour and every word I wrote about his tragedy.

All sorts of problems lay ahead of me, but I would never have a problem with the voice.

It’s easy to recognise a writer who’s just come from their desk. You can see it in their haunted eyes, as if they’re still living in another world. This manuscript is that world. It is where I lived a thousand days, always confident about the voice but, Lord … what was it really like to be an Irish immigrant a century ago? What was it like to be 16, locked inside a cell in Beechworth. What were the dimensions of the cell. Where was the shelf, the cruel unbending bed? What does a boy feel to have his father stolen from him, handcuffed to the stirrup iron of a policeman’s mare. My notebooks are a mess of endless questions, inept drawings. What happens when Easter arrives in Australian autumn instead of Holy Irish spring? When the convicts were transported was the banshee left behind? For Ned to come alive I needed to think of things we had never thought before. That is the thrill and the terror of a writer’s life, to walk out on the tightrope every day. The manuscript reveals none of this.

Papers and drafts of True History of the Kelly Gang. Photograph: State Library Victoria

If you read the bottom left-hand corner of the manuscript you will easily learn what words were printed on a given day. But there is nothing to show what words have been inserted, transposed, deleted, when the banshee crawled in from the dark.

You could ask my computer if you had the skill, but the computer isn’t talking and the only way to get the information is to read all 4,000 pages of the manuscript, not like you or I might read a finished book, but like a saint or mad person in a cell, someone with patience to annotate a river or a cloud.

A hardcover edition of True History of the Kelly Gang. Photograph: State Library Victoria

As it happens, my published novel imagines this very reader. Is it he or she or they? A librarian perhaps? It is a someone I invented, a someone who has collected Ned’s scattered pages and collated them into 13 parcels. This has allowed me to map the passage of time, to add layers of information, and also – an important point – provide chapters for my readers.

Of course my Ned was not thinking in terms of books or chapters. He had no time for commas and it is this that gives his voice an urgency and passion, never pausing when it would be grammatically correct to do so.

“This is a fabulous story,” my New York agent said, “But you don’t need to write it like this.”

But I did need to write it just like that. And she was the excellent agent who had long ago introduced me to Gary Fisketjon (who published Cormac McCarthy) and who I knew would surely know how to read what I had written.

I had never wished for line editing from anyone, but now I welcomed Gary’s insistent questioning. Yes he was American and we can be amused that he queried the word mopoke. But he got the book, loved the book, never relented in his demand that it be as good as it could be, that the jacket be right, that the map be perfect. There was no escape from his passion. He tracked me down in Europe and spent five hours on the phone arguing about ampersands because he wanted posterity to fully understand that you knew what you were doing. He made lists for the foreign publishers and proofreaders who would publish later, just so they would understand that what might be an error in The Chicago Manual of Style was exactly what the author wished in print.

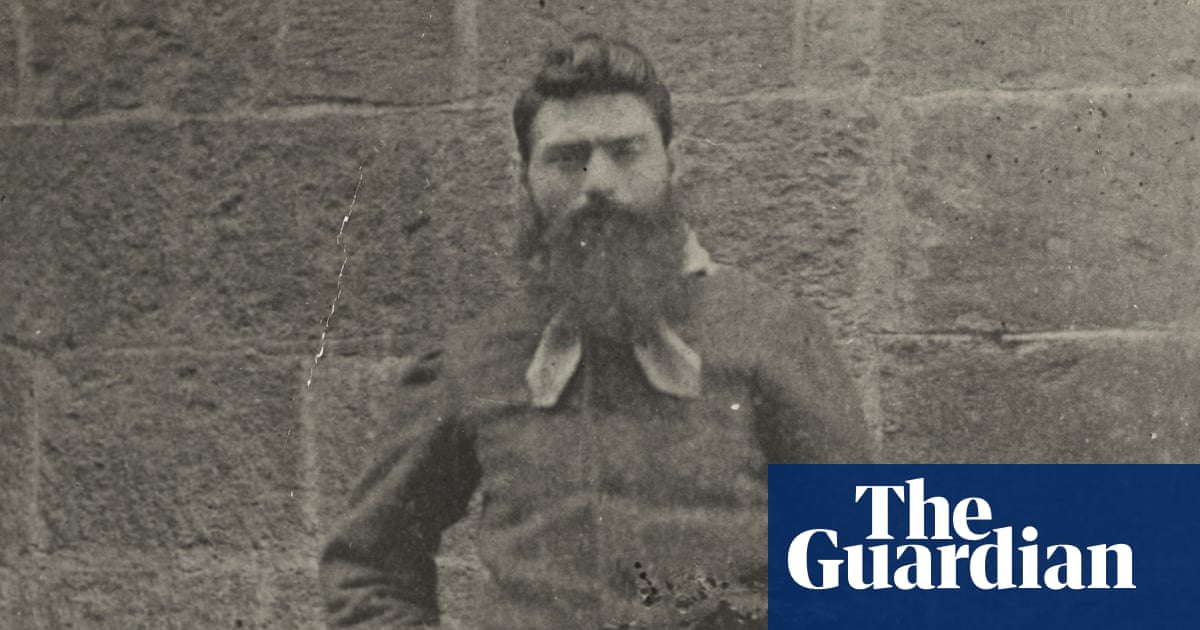

Ned Kelly in Chains taken by photographer Charles Nettleton. Photograph: State Library Victoria

Gary went out on a limb for that book, sold it to the sales force, the booksellers and anyone else who would listen to him. Finally I knew what writers mean when they say they were “well published”.

Some have questioned my title, but Gary never did. He trusted the book was what Ned named it, with a label declaring it was the true story of a widow’s son who had been subject of perjury, false witness by the police and press. True History it must be and nothing less.

This is an extract from State Library Victoria’s exhibition Creative Acts: Artists and their Inspirations, on from 15 August 2025 to 31 May 2026