On Aug. 11, 1965, 60 years ago, I stood transfixed with hundreds of others on the corner several blocks from my house in South L.A. watching what seemed like a horrid page out of “Dante’s Inferno.”

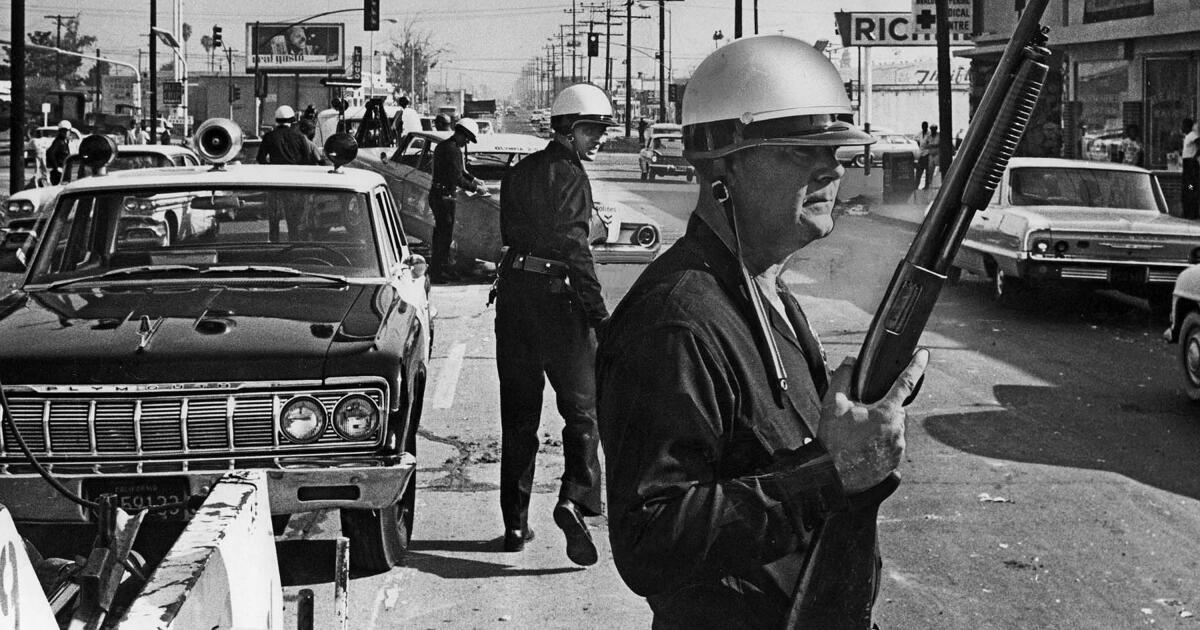

But this was real life. Liquor stores, a laundromat and two dry cleaners blazed away. There was an ear-splitting din from the crowd’s shouts, curses and jeers at the police cars that sped by crammed with cops in full battle gear, shotguns flailing out of their cars.

There was an almost carnival air of euphoria among the roving throngs as packs of young and not-so-young people darted into the stores snatching and grabbing anything that wasn’t nailed down. Their arms bulged with liquor bottles and cigarette cartons. I was 18 and felt a childlike mix of awe and fascination watching this.

For a moment there was even the temptation to make my own dash into one of the burning stores. But that quickly passed. One of my friends kept repeating with his face contorted with anger: “Maybe now they’ll see how rotten they treat us.” In that bitter moment, he said what countless other Black people felt as the flames and the smoke swirled.

The events of those days and his words remain burned in my memory on the 60th anniversary of the Watts riots. I still think of the streets down which we were shooed by the police and the National Guard during those hellish days.

They’re impossible to forget for another reason. Exactly six decades later, some of those streets look as if time has stood still. They are dotted with the same fast-food restaurants, beauty shops, liquor stores and mom-and-pop grocery stores. The main street near the block I lived on then is just as unkempt, pothole-ridden and trash littered now as it ever was. All the homes and stores in the area are hermetically sealed with iron bars, security gates and burglar alarms.

In taking a hard look at what has changed in Watts — and all of America’s neighborhoods like Watts — since the riots, the picture is not flattering. According to Data USA, Watts still has the runaway highest poverty rate in L.A. County. Nearly one-third of the households are far below the official poverty level. It has the highest jobless rate. It is still plagued by the same paucity of retail stores, healthcare services, chronically low educational test scores and high dropout rates.

The near-frozen conditions in Watts were hideously punctuated in the lengthy battle that residents and advocacy groups waged last year against city agencies to clean up the contaminated water that posed huge safety and health hazards to thousands. It’s a battle that’s still being fought.

In some ways, what I see in Watts now is worse than what I remember before the riots. Despite the grinding poverty among many in Watts six decades ago, nearly all the residents had shelter. The sight of people sleeping on the streets, at bus stops and in the park was practically unimaginable in Watts in 1965. That is not the case today. Homelessness, as in other parts of South Los Angeles, is a major problem.

However, this is only one benchmark of how little progress has been made since the riots in confronting racial ills and poverty in a still grossly underserved Watts.

Many Black people in the six decades since the riots have long since escaped such neighborhoods. Their lives, like mine, are now lived far from the corner in South L.A. where I once stood amid the flames and chaos. Their flight was made possible by the avalanche of civil rights and voting rights laws, state and local bars against discrimination, and affirmative action programs that for many of them crumbled the nation’s historic racial barriers. The parade of top Black appointed and elected officials, including one former president, the legions of black mega millionaire CEOs, athletes and entertainers are evidence of that.

However, that does not alter the hard reality that a new generation of Black people now languishes on corners like the one I stood on in August 1965. For them there has been no escape.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. There are advocacy groups such as Watts Rising that press L.A. city and county officials for greater funding initiatives and programs in every area of life, including housing, jobs and income boosting programs, along with huge investment in improved healthcare services.

One other memorable moment for me during those hellfire days was when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. came to Watts at the height of the riots. He was jeered by a few Black residents when he tried to calm the situation. But King did not just deliver a message of peace and nonviolence; he also deplored police abuse and the poverty in Watts. Sixty years later, he would almost certainly have the same message if he came to South L.A. or any of America’s other similar neighborhoods. Too little has changed. Too much has gotten worse. What I see in those communities 60 years after the Watts riots remains stark and troubling proof of that.

Earl Ofari Hutchinson’s latest book is “Day 1 The Trump Reign.” His commentaries can be found at thehutchinsonreport.net.

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

-

The author presents a deeply personal account of witnessing the Watts riots firsthand as an 18-year-old, describing the scene as resembling “Dante’s Inferno” with burning buildings and crowds looting stores while police sped by in battle gear. The visceral memory includes a friend’s angry declaration that “maybe now they’ll see how rotten they treat us,” capturing the sentiment that the riots were a desperate response to systemic mistreatment.

-

Six decades later, the author argues that conditions in Watts have remained largely stagnant, with the same types of businesses, pothole-ridden streets, and security measures like iron bars and burglar alarms. According to the author’s observations, Watts still suffers from the highest poverty rate in L.A. County, with nearly one-third of households below the poverty level, along with persistent problems including high joblessness, poor retail access, inadequate healthcare services, and low educational performance.

-

The author contends that in some respects, conditions have actually deteriorated since 1965, particularly noting that homelessness was “practically unimaginable” in Watts during the original riots but has now become a major problem throughout South Los Angeles. This represents a stark decline from when “nearly all the residents had shelter” despite widespread poverty.

-

While acknowledging that many Black Americans have successfully escaped such neighborhoods through civil rights progress, including anti-discrimination laws and affirmative action programs that produced prominent officials and business leaders, the author maintains that “a new generation of Black people now languishes” in similar conditions without viable escape routes.

Different views on the topic

-

Contemporary public officials and conservatives interpreted the Watts riots fundamentally differently, viewing the violence as “wanton lawlessness” rather than justified protest, pointing to the large number of minority men with criminal records and the influx of “outsiders” from the South as contributing factors[2]. They argued that looters took far more goods than they could use and questioned the rationality of destroying one’s own neighborhood[2].

-

Some officials and media outlets characterized the riots as “an insurrection fostered by urban gangs or by the Black Muslim movement,” which mainstream press regarded as a radical cult, rather than as a community response to systemic problems[2]. This interpretation focused on organized criminal elements rather than broader social grievances.

-

Federal officials and some reporters offered a contrasting perspective, explaining the riots as “a protest against the poverty and hopelessness of life in the inner city,” describing challenges of joblessness and lack of basic services in South-Central Los Angeles[2]. This interpretation aligned with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “war on poverty” programs and suggested the riots demonstrated the need for such federal intervention[2].

-

An official investigation prompted by Governor Pat Brown found that the riot resulted from “the Watts community’s longstanding grievances and growing discontentment with high unemployment rates, substandard housing, and inadequate schools,” contradicting claims by public officials that the riots were caused by outside agitators[1]. However, despite these findings, city leaders and state officials failed to implement measures to improve conditions for African Americans in the Watts neighborhood[1].