Editor’s note: This article is part of the Program Builders series, focusing on the behind-the-scenes executives and people fueling the future growth of their sports.

One of the great NFL turnarounds began with a phone call.

On New Year’s Eve in 2012, Andy Reid walked out of a farewell party on his final day with the Philadelphia Eagles. He had been fired after 14 seasons and the final moments had been bittersweet — a tearful meeting with his players and a goodbye to team employees.

As he left the office for the final time, his phone lit up. It was Clark Hunt, the owner and chairman of the Kansas City Chiefs.

Hunt had one question on his mind: Did Reid still want to coach? Reid was 54 and coming off a grueling 14-year stretch in Philly, an arduous slog of media scrutiny, heartbreaking postseason losses and, earlier that year, the loss of his oldest son, Garrett, to a drug overdose.

Yet a better question might have been: Why would Reid want to coach the Chiefs?

Few franchises had gone through an uglier season than the 2012 Chiefs. They had finished 2-14 — the worst record in team history. They didn’t have a good quarterback, let alone a franchise one. They hadn’t won a playoff game in 19 years and had experienced off-the-field tragedy. Just a month earlier, Chiefs linebacker Jovan Belcher had killed his girlfriend, driven to the team practice facility, and died by suicide in front of team employees, leaving the whole organization shaken.

The Chiefs did not just need a new head coach, Hunt would say later. They needed a new brand, a new strategy and a new culture.

What they needed was a wholesale turnaround.

In the business world, there is a term for the person charged with improving a struggling company: the Turnaround Leader.

In the early 2000s, Rosabeth Moss Kanter, a professor at Harvard Business School, set out to understand why some Turnaround Leaders succeed and others falter. The biggest reason, she believed, was confidence.

“Leadership is not about the leader,” Kanter wrote in her book, “Confidence: How Winning Streaks & Losing Streaks Begin and End.” “It is about how he or she builds the confidence of everyone else.”

Kanter built a framework for Turnaround Leaders:

1. Espouse: The Power of Message

“Leaders articulate values and vision and deliver pep talks.”

2. Exemplify: The Power of Models

“Leaders showcase the accountable and collaborative behavior they expect from others.”

3. Establish: The Power of Formal Mechanisms.

“Leaders create process, structure and routine.”

Kanter theorized that nearly every successful turnaround — whether it’s a Fortune 500 company, a school or a football team — has leadership that exhibits those behaviors. The Turnaround Leader excels at identifying hidden talent, rebuilding culture, communicating directly and sparking creativity and collaboration.

Early in his career, Peter Cuneo helped lead turnarounds at companies like Bristol Myers Squibb and Remington Products. But his biggest came 25 years ago, when he became CEO of Marvel Entertainment.

Marvel, the iconic comic-book brand, had gone bankrupt. Its culture was stale. Cuneo was present as the company dusted itself off, rebuilt its strategy around licensing its thousands of characters and reaped the rewards as a group of visionary leaders turned the brand into one of the powerful forces in Hollywood history, eventually selling it to Disney for $4 billion.

“I’ve been a part of seven turnarounds, and in the businesses I’ve been in, it’s almost always poor leadership,” Cuneo said during an interview. “It’s leadership that lacks courage.”

In the 12 years since Andy Reid accepted Clark Hunt’s offer to coach the Chiefs, the franchise has transformed into one of the more respected and successful in the NFL, winning three Super Bowls and playing in two more, including a loss last season to the Philadelphia Eagles.

While the arrival of quarterback Patrick Mahomes elevated the Chiefs to the next level, it was the culture and foundation in the early years that allowed Mahomes to thrive. Before the Super Bowl parades, there was the turnaround, and whether Reid knew it or not, the process he carried out shared most of the attributes — and therefore the lessons — of a great corporate turnaround.

Lesson 1: You don’t want to dwell on the past. But you do need to learn from it.

In the days after Reid arrived in Kansas City, Dustin Colquitt, the Chiefs’ veteran punter, was working out at the team facility, preparing for the Pro Bowl. Reid sent word down to Colquitt that he wanted to meet, and after eight years in the NFL and four head coaches, Colquitt interpreted that to mean one thing: Now.

But the invitation from Reid came with a surprising caveat. Reid wanted Colquitt to see him after he finished his work. When Colquitt entered the coach’s office, Reid had two questions: He asked Colquitt if he preferred to stay with the Chiefs or earn a fresh start somewhere else, allowing the veteran a sense of agency. Then he asked about the state of the team’s culture.

It was no secret that morale had flatlined. In the previous two seasons, the organization had weathered a series of public hits. The team was facing a lawsuit over age discrimination. (It was settled out of court.) Former coach Todd Haley had told The Kansas City Star that he suspected rooms at the team facility were bugged. And the lines of communication throughout the organization were severed, leaving players worried about snitches and backbiting.

It felt, Colquitt said, like “everyone was on a chopping block.”

“There was always a notion of like, even if guys have incentives in their contracts, if they’re getting close, we’re not going to let them get there,” Colquitt said.

Reid listened as Colquitt talked, then offered his own message: It’s gonna be drastically different.

At one of his first team meetings, Colquitt recalled, Reid addressed the elephant in the room. “I want you guys to make as much money as you can,” he said. “If you’re helping us, I want to help you.”

Lesson 2: Start with culture. In a losing organization, it’s always worse than you think.

At some point around the time he hired Reid, Clark Hunt realized the Chiefs did not have an organizational culture. Reid set out to change that. He focused on simple values like honesty, respect and caring. He told players to be themselves and showcase their personalities. In meetings, he outlined a set of hard-line rules and boundaries, then gave players the freedom to exist within them.

“Simple stuff,” said Chiefs special teams coach Dave Toub. “Be on time. Do the right thing off the field. Be careful with the media, with what you say.

“You got to set those parameters, and you can’t change from them. If somebody doesn’t do it, you got to get them out of there.”

When Reid worked in Philadelphia, Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie promoted a key rule: Treat the janitor exactly the same as you treat me. When Reid brought the ethos to Kansas City, it reminded Hunt of his father, Chiefs founder Lamar Hunt.

“I think it’s built on respect for each other,” Hunt said. “That’s really just part of Andy’s makeup.”

Soon enough, Hunt said, the Reid culture became the Chiefs’ culture.

“I would credit Andy Reid a lot with the culture that we have,” Hunt said.

The respect stretched to other corners of the building, where employees had long felt neglected. Reid started a tradition of inviting coaches’ wives to join the traveling party for one trip each year. He told players he wanted to see their families celebrating on the field after wins.

“He knows how to treat everybody the same, which is differently,” Colquitt said. “He embraced every guy and their personality and what they brought off the field. A lot of coaches would be like: ‘I don’t care what you have going on outside, we got to focus in here.’ And he said: ‘We care about you, whatever you have personally going on off the field.’”

Lesson 3: Let people know where they stand. Then move forward together.

When the Chiefs gathered for offseason training activities before Reid’s first season, they discovered a new tradition: They had to complete a conditioning test.

It wasn’t unheard of in the NFL. But Reid took it more seriously than most. Players had to work up to, and then complete, 16 half-gassers — an up-and-back sprint across the width of the field — in an allotted time.

“There’s a mentality with that,” said Chiefs offensive coordinator Matt Nagy, who was then the quarterbacks coach. “It’s not a country club. It’s something for us to be able to know: We’re going to grind. We’re gonna work hard. We’re gonna build this brotherhood.”

For Reid and his staff, the mentality began that first year at training camp, where they piled into dorms at Missouri Western State University, an hour north of Kansas City. The accommodations were Spartan; plain walls and few furnishings. Practices were breakneck. The staff overloaded the offense with installations and concepts, then offered clear, concise and direct feedback.

By doing so, Reid created a standard and expectation.

“You gotta be honest with your players,” Nagy said. “They know how to read whether you’re honest or not. And then you gotta practice hard. I think that’s one of the things we’ve always done with Coach Reid.”

Lesson 4: Everyone knows communication is key. But is it good communication? Is it consistent?

One of the pieces of organizational infrastructure that Reid brought with him from Philadelphia was something he called the “Unity Council.” It consisted of appointed leaders from each position group, and every Wednesday morning, they would gather with Reid for a quick meeting.

The council was not designed for X’s and O’s. It was meant to create a safe space for players to voice concerns emanating from the rest of the roster.

One of the early tests during Reid’s tenure, for instance, came when the Chiefs started winning, which caused the cost of players’ tickets to jump by close to 50 percent. The players in the Unity Council did not think it was fair that they were doing the winning and paying more for tickets.

“We took that to Andy, and that was done that day,” Colquitt said.

Reid emphasized informal communication, too. He opened lines at practice, asking players to deliver feedback. He extolled creativity and collaboration. He filled the playbook with gadget plays and exotic formations. The plays were chosen because the staff thought they might be successful. But Reid also believed there was value in allowing players to have more fun.

Reid rarely yelled, but he was always firm. He prided himself on never losing control. When long snapper James Winchester joined the roster two years later, he realized that Reid’s displeasure would come out in subtle ways.

“The worst you’re gonna get from Coach Reid out on the field is like a ‘pick it up’ or ‘come on, man,’” Winchester said. “That ‘come on, man’ really cuts you deep. It’s like my dad just said: ‘Pick it up.’ And guys respect that.”

The communication style paid off in clear ways. The year before Reid arrived, the Chiefs’ practice facility was a ghost town on Tuesdays, the NFL’s traditional day off. In Reid’s first year, it was often packed. Colquitt would show up to work, and there would be 35 or 40 players in the building, working out, receiving treatment, hanging around the locker room, just talking. It was a culture Reid fostered.

The Chiefs finished 11-5 in Reid’s first season, the franchise’s most victories in a decade. They returned to the postseason. And although they missed the playoffs the next year — finishing 9-7 — they returned to the postseason again in 2015 and haven’t missed it since.

The arrival of Mahomes took the franchise to new heights and a trio of Super Bowl championships followed. But the foundation was laid years earlier.

The turnaround wasn’t an anomaly; it was a blueprint.

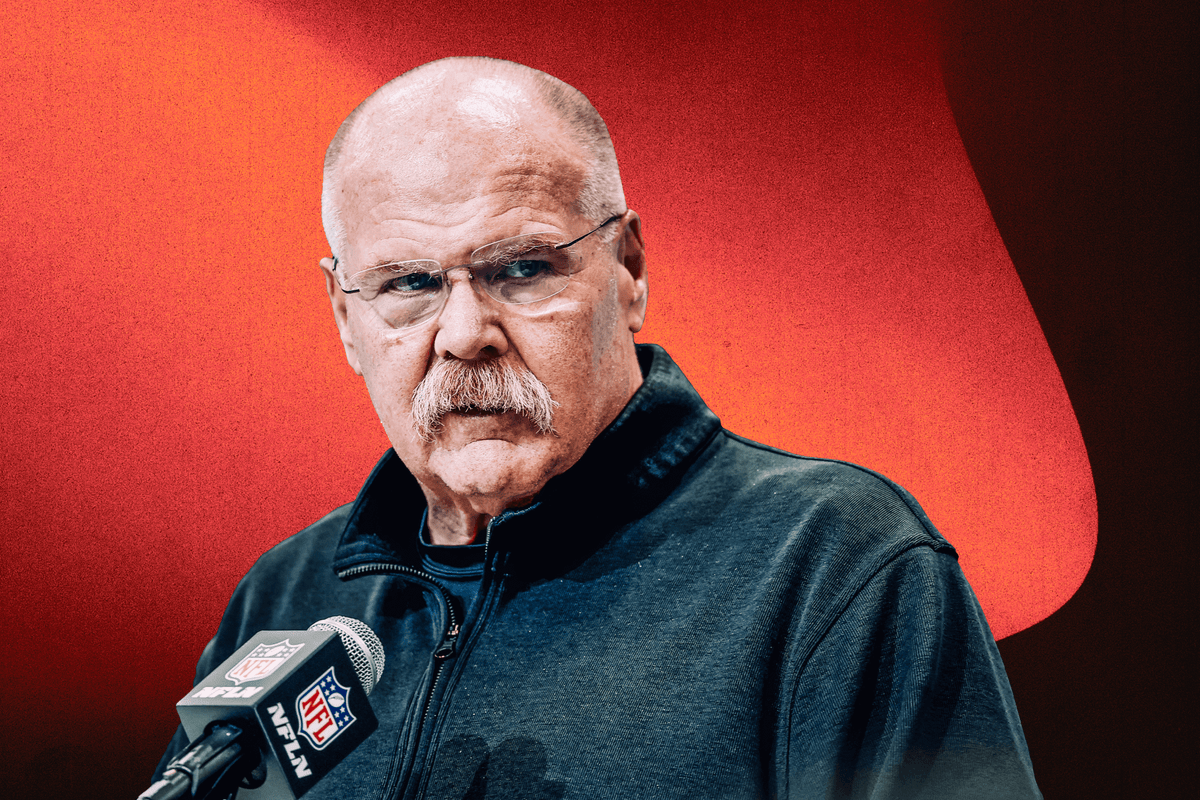

(Illustration: John Bradford / The Athletic; Stacy Revere / Getty Images)