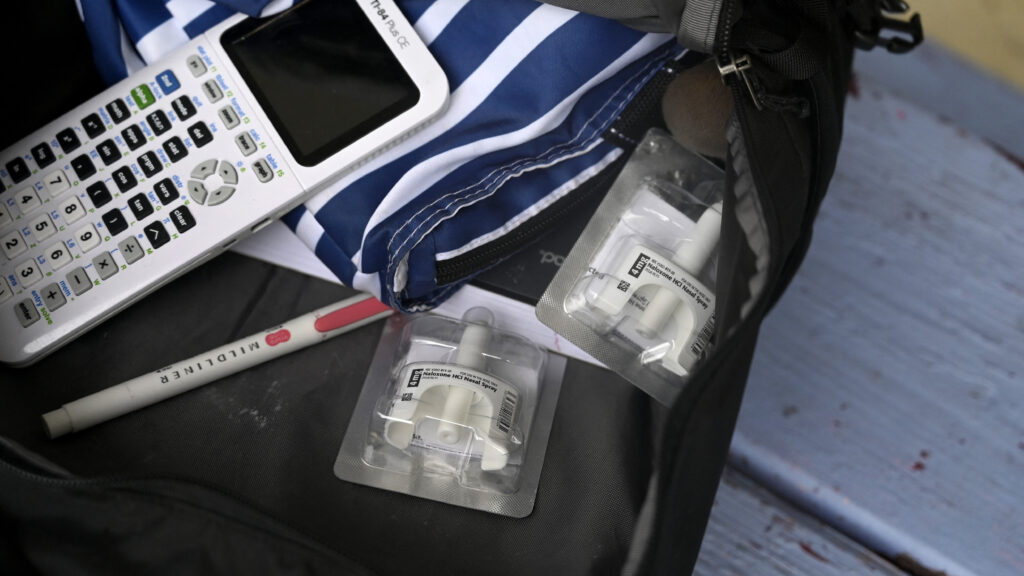

By the time we snap her boxes shut, we’ll have it all in there: twin XL sheets, shower caddy, extra chargers.

And Narcan.

I’d be lying if I said that last one didn’t stop me cold.

My daughter is leaving for college in a couple of weeks. She’s a careful, cautious kid. A conservatory-bound graduate who won’t even touch caffeine before a performance.

But this isn’t about her. It’s about the roommate. The classmate. A stranger at a party. Isn’t it always someone else’s kid?

As I put Narcan in the cart — one hand over my heart and the other over the womb that brought her into this world — the mother in me was between weeping and vomiting. The realist in me knew better. Because in 2025, packing an overdose-reversal spray for college is, or should be, a new kind of parental instinct.

I packed it because my daughter might be the one holding it when it counts.

And the only reason she can?

The work of public health.

Sedative ‘dex’ is replacing ‘tranq’ in illegal drug supply and causing excruciating withdrawal

Because of the unglamorous, underfunded, lifesaving work of the World Health Organization, the National Institutes of Health, state health departments, and a quiet army of scientists and public servants who never stopped believing that drug misuse isn’t a moral failing — it’s a treatable medical condition.

Narcan (naloxone) reverses opioid overdoses in seconds and is as simple to use as nasal spray for allergies. I bought it for $45 on Amazon. That I could — that I felt I had to — says everything about the moment we’re living in.

Despite a significant drop in deaths among some populations in recent years, nearly 55,000 people died from opioid overdoses in the U.S. in 2024. And while the national decline is encouraging news, overdoses are still the leading cause of death for Americans aged 18-44.

But Narcan didn’t just magically show up on pharmacy shelves. It exists because people made it happen.

Naloxone was created in the early 1970s, reserved for emergency medicine. By 1983, the World Health Organization listed it as an “essential medicine.” In the following decades, as opioids evolved, so did the need for innovation. That led researchers at the National Institutes of Health to get this powerful prescription into a more user-friendly form — nasal spray — which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015, but still limited to medical professionals.

Meanwhile, the WHO was behind the scenes ensuring its eventual over-the-counter form would get fast-tracked. At the same time, law enforcement agencies and health departments were actively rolling out training.

In 2023, the FDA greenlit an over-the-counter spray that enabled non-clinicians to provide second chances without a second thought.

That’s how Narcan ended up in our medicine cabinet — and my 18-year-old daughter’s first-aid kit.

That’s also the best of public health.

And now? Congress is turning its back as the Trump administration defunds the WHO and slashes 40% of NIH’s budget, not to mention squeezing every drop of funding from health services and research — the very forces behind this lifesaving work.

Public health leaders, besieged and regretful, talk of re-establishing trust

Look, I’m not a doctor, though I’ve worked in health care for years. I’m a mom. A citizen of a country where overdose kills far too many — and where a growing number of politicians treat public health like a partisan punching bag instead of what it actually is: national defense in a lab coat.

I also live in rural New Hampshire, where folks like me carry Narcan in their Subaru glove compartments because we’ve seen too much to pretend otherwise.

When we close the last of her boxes and hug our daughter goodbye, my husband and I will feel it all — pride, heartbreak and hope.

We’ll also feel gratitude.

For the scientists and health professionals who’ve been with us from the start to keep our kid safe — her first vaccines, her first period, her first broken bone, her first experiments with love. Now, as she heads off on her first great adventure, public health will be there quietly protecting her when we’re no longer down the hallway.

I pray she never needs that Narcan. But some kid down her hallway might.

There is no question that we have public health to thank for keeping our children alive. I hope in this moment we can thank elected officials for keeping public health alive.

Elizabeth Métraux works in communications for the United Nations Foundation and was formerly at the National Institutes of Health and the Vermont Department of Health.