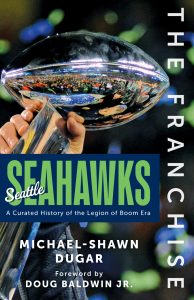

The following excerpt from The Franchise: Seattle Seahawks: A Curated History of the Legion of Boom Era by Michael-Shawn Dugar is reprinted with the permission of Triumph Books. It has been lightly edited in spots for context and clarity. You can find more information and order a copy here.

Marshawn Lynch imagined this moment countless times as a kid growing up in North Oakland:

“It’s the end of the game … one more play … the quarterback hand the ball off to Marshawn … he jump in the end zone — touchdown! The Oakland Raiders win the Super Bowl!”

The final seconds of Super Bowl XLIX between the Seattle Seahawks and New England Patriots nearly played out that way.

With Seattle on the New England 5-yard line, trailing 28-24 with 1:06 remaining, NBC’s Cris Collinsworth said, “Now you have to stop Marshawn Lynch.” Then Russell Wilson put the ball in Lynch’s hands.

“Here he goes,” play-by-play man Al Michaels said as the running back plowed forward. “Beast Mode! To the half-yard line!”

Offensive coordinator Darrell Bevell recalled that the Seahawks had failed on a pair of short-yardage runs earlier in the game: Vince Wilfork blew up a third-and-2 shotgun run for no gain in the first quarter, and linebacker Rob Ninkovich did the same on a third-and-1 carry in the third quarter. With those plays in mind, Bevell didn’t think Lynch would just walk into the end zone if he called another run play on second down. Even though Lynch was also successful on a three-yard touchdown run on third-and-2 in the second quarter and produced a first down on a second-and-1 run in the third, Bevell believed he made the right decision based on the situation.

Obviously, Lynch could have scored the game-winning touchdown, but when Bevell hears that he made the worst call of all time, “I would not agree with that” is his retort. As for the specifics of the play he chose, Bevell felt good about giving Wilson options: he could go to Doug Baldwin if the Patriots were in zone coverage, Ricardo Lockette if they were in man-to-man.

“The process was solid,” Bevell said. “And I think the play call gave us a great opportunity to be very successful.”

Choosing to throw on second down may have made sense to the coaching staff, but not to the dreamer from North Oakland.

“Not only did they take a ring, a moment — they took a dream,” Lynch said. “That’s a once-in-a-lifetime situation.”

There wasn’t any debate or discussion of audibling when Russell Wilson said the call. Sure, players I’ve spoken with had their objections, but they didn’t feel it was their place to express it in that moment. Wilson was among the most powerful players in the huddle, and he fully believed in Bevell’s call. So that left only Baldwin, Lynch, and possibly veteran center Max Unger as the guys with the cache to overrule the decision, although that would likely have required burning the team’s final timeout. So onward they went.

Because receiver Chris Matthews had torched the Patriots earlier in the game, Brandon Browner replaced Logan Ryan as Matthews’ primary defender. This substitution thrust backup cornerback Malcolm Butler into the game. On this final play, Browner lined up directly over Jermaine Kearse. Butler was several yards deep into the end zone, aligned over Lockette.

Kearse figured there were two ways to play it: either Browner would take Lockette, or they’d “lock” it, meaning the defenders follow who’s in front of them. Butler and Browner chose the latter because they knew what was coming. Kearse thought it’d be an easy touchdown if he could disrupt Browner. But the bigger and stronger Browner overpowered Kearse, and Butler predicted a slant pattern by Lockette based on the receiver keeping his head forward then immediately turning to Wilson after jabbing outside with his right foot.

Seattle’s longtime play-by-play announcer Steve Raible described what followed:

“Lynch in the backfield … Russell looks, throws inside … OH MY GOD, IT’S PICKED OFF … AT THE GOAL LINE … IT’S PICKED OFF BY BUTLER … INTENDED FOR LOCKETTE AT THE GOAL LINE!”

Malcolm Butler undercuts Ricardo Lockette to intercept Russell Wilson in the final seconds of Super Bowl XLIX. (Mark J. Rebilas / Imagn Images)

The atmosphere inside Seattle’s locker room was one of tragedy. One year earlier, Lynch made sure Philthy Rich’s “Ready 2 Ride” blasted throughout the room in celebration of their triumph. This time, Lynch was fully dressed, headphones on, beelining for the exits by the time his teammates even arrived to a locker room soundtracked by silence.

Heartbreak, despair, disgust, frustration, disbelief, and confusion filled the air. Tears flowed from the faces of coaches, executives, and players. Some players were inconsolable. Others were enraged, yelling and screaming at one another, and even some coaches. A backup defensive lineman punched a wall and injured his hand. Everyone I’ve ever spoken with described a dark, ominous room, like life had just been zapped from them, and they were all living the same nightmare.

“It’s like a death,” longtime vice president of player engagement Mo Kelly said. “It’s hard to ever get over that.”

Getting over it was harder for some than others. The first step was hearing why they decided to throw the ball in that situation. Pete Carroll doubled down on his thought process: to get four bites at the apple with only one timeout, they had to throw ball at some point. It was sound logic schematically — but logic his locker room wasn’t interesting in hearing, largely because they believed anything other than trusting Lynch to get across that line was flawed thinking. Throwing the ball was largely viewed as such a ludicrous notion that it birthed the conspiracy theory that Carroll and Bevell called that play to try and ensure Wilson won the MVP over Lynch, who at the time was feuding with the front office and making headlines for his rebellious stance against the press. Lynch publicly wondered if the coaches had plotted against him in that way. Carroll and Bevell are adamant that such a notion is ridiculous. Carroll isn’t one to hold grudges, but he was upset his players were foolish enough to think he gave a damn about the MVP.

When Carroll addressed the team at their meeting back in Seattle, he tripled down on the thought process and went as far as to say he’d throw the ball again if presented the same scenario. The room fell silent. Then the culture really started to fall apart.

“You already punched me in my stomach once,” one player told me of his reaction to Carroll’s explanation, “and he just took a knife this time and put it through my soul.”

The Super Bowl loss and Carroll’s reasoning behind the final play did irreparable damage to the Seahawks and their culture. For years, the players had essentially been programmed to believe they were a family. They internalized that idea and lived by it. This was especially true for the players whose only NFL experience was in Seattle. Losing the Super Bowl in that manner led them to poke holes in the message and the philosophy, like children growing up and bucking back at parents who they learned have been deceiving them. Their identity was to run the ball, but they felt they unnecessarily abandoned it when it mattered most.

The Seahawks had been built around a collection of players who shared a familial bond. The bond was broken and shattered after the Super Bowl. The trust they once had was replaced by finger-pointing and skepticism. There wasn’t a single dramatic blowup that made people feel this way, it was more a slow, drawn out feeling of division. But Carroll’s explanation in the team meeting didn’t help, neither did offensive line coach Tom Cable redirecting the blame, saying that if the defense hadn’t blown a 10-point lead in the fourth quarter there’d be nothing to talk about. Cable’s comment infuriated members of the defense. Any hope that the players wouldn’t leave for the off-season with lingering bad feelings was gone.

“We didn’t trust each other,” K.J. Wright said, describing the aftermath. “We didn’t connect with each other. It was a dark, gray cloud hovering over us. For it to get addressed the way it got addressed and for us to not talk about it — we needed therapy. If it was me, we’d have had therapy to let it out.”

Wilson organized a trip to Hawaii for his teammates, with over 30 attendees. He wanted them to hang out and air their grievances in a safe space. It worked for some of the guys. They let it all out on the island and were able to leave the past where it belonged. It didn’t work for everyone, though. And Wilson didn’t make the situation any better by echoing Carroll’s sentiment that he’d run the same play again if given the opportunity. Wilson had every right to share his truth but that’s not a truth anyone wanted to hear, especially if their truth was that doing anything other than handing the ball to Lynch was idiotic and unforgivable. The Hawaii trip was a decent idea, but it was mostly a flop.

The Seahawks had become the spouse who stayed with their partner after being cheated on. The relationship remained intact, but the connection wasn’t as strong. They forgave but didn’t forget, and the feeling never faded. A text message here, a dinner conversation there. Venting to Kelly and longtime equipment director Erik Kennedy. A meeting before losing to the Packers in Week 2 of the 2015 season. Richard Sherman calling out the offensive coaches on the sideline on national television over a failed goal-line pass in 2016. An ESPN The Magazine article in 2017 explaining why Sherman won’t let it go. A Sports Illustrated article in 2018 about other teammates basically feeling the same way. New coaches that joined the staff in 2018 could feel that players couldn’t get over the fact they were only one-time champions.

“It lingered,” Baldwin said in 2022. “We did our best to try and come out of it but … you got guys who are legitimately killing themselves. Every time you step out on that field and you get hit, you’re taking days off your life. You have guys who are legitimately killing themselves to get to that moment. We were on the 1-yard line. There’s nothing that’s going to stop Marshawn and that offensive line from getting in the end zone.”

(Photo of Marshawn Lynch: Christian Petersen / Getty Images)