A week dedicated to the stories from New York’s uniquely ubiquitous housing option.

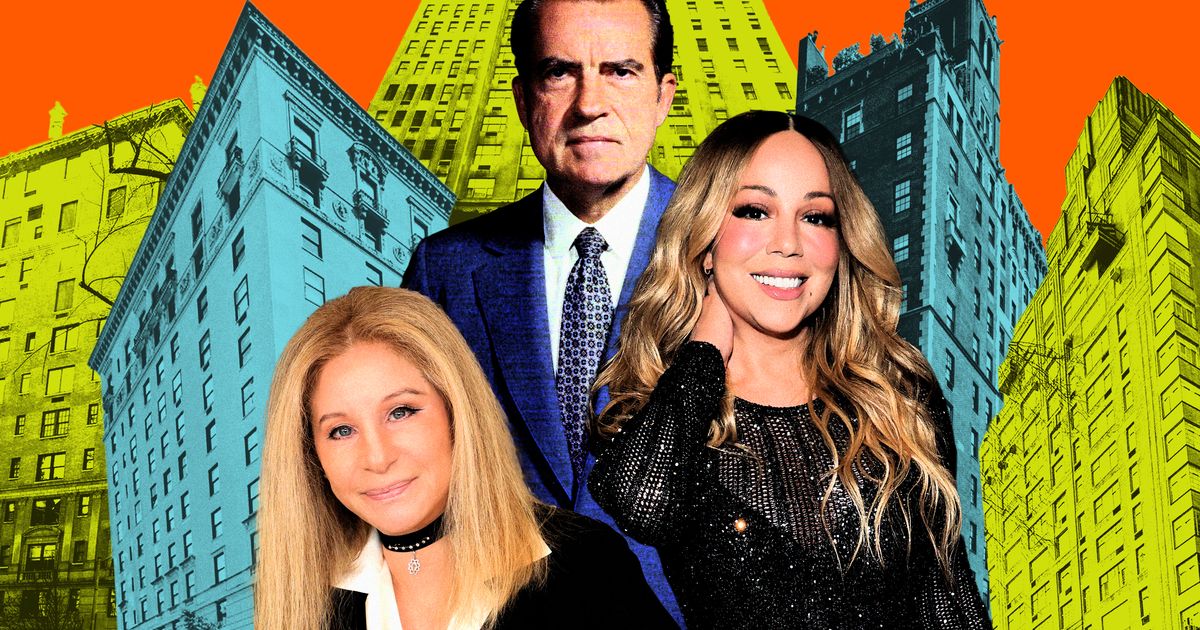

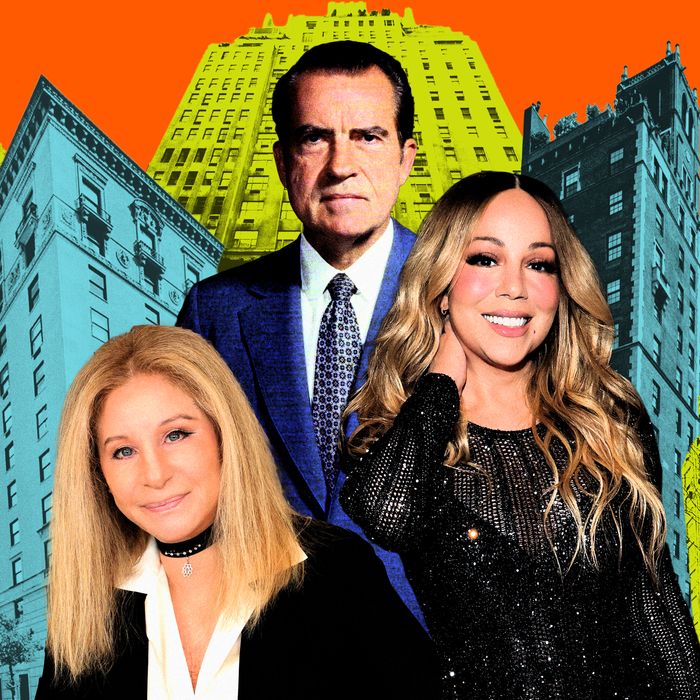

Photo-Illustration: Curbed; Photos: Compass, City Realty, Getty Images

“I was going to buy it, I was going to pay cash, I wanted this apartment bad,” Livvy Dunne, a 22-year-old social-media influencer and former college gymnast, told her TikTok followers in July after the board of an Upper West Side co-op blocked her purchase of a three-bedroom that had once belonged to Babe Ruth. Dunne made the mistake — common to celebrities and all-cash buyers unfamiliar with the ways of Manhattan real estate — of thinking that wanting an apartment and having the money to buy it meant she could. She may be forgiven the error: Besides her being 22 and having a broker who was apparently “so confident” the deal would go through, the era of the celebrity co-op rejection has largely passed.

For decades, though, the tabloids were filled with the weird, only-in-New York phenomenon whereby the rich, accomplished, and famous — Gloria Vanderbilt, Ron Perelman, Diane Keaton, Steve Wynn, Richard Nixon — were routinely barred from buying in the city’s most desirable buildings. Some were rejected from multiple co-ops, like Barbra Streisand, who spent several years in the late 1960s trying to buy an apartment in one of the Upper East Side’s “good” buildings. She was turned away from 1021 Park (“We don’t want flamboyant Hollywood types”), 927 Fifth (“She’d probably give a lot of parties”), and 1107 Fifth (allegedly because of concerns she might build a recording studio there). Even letters from Governor Nelson Rockefeller, Mayor John Lindsay and her current Central Park West co-op attesting to her quiet, homebody nature couldn’t get her past an East Side board. And those were just the buildings she applied to: Being Jewish, she was reportedly advised against trying for several others, including 740 Park. Certainly, it also didn’t help that she was an actress and divorced; being single was reason enough for a board turndown back then. As was being a Democrat — the reason Peter Lawford and his wife Patricia Kennedy, JFK’s sister, were turned away from 117 East 72nd.

Eventually, Streisand gave up and renovated her triplex at the Ardsley on Central Park West, where buildings are known for being far more liberal in their requirements than across the park. Still, it wasn’t exactly anything goes: Mariah Carey was blocked from buying Streisand’s triplex in 1999, and a board member told the New York Daily News that “if we let her in, we’d have to let everybody in.” (According to Steven Gaines’s The Sky’s the Limit, the only board member to vote in Carey’s favor was Diane Keaton, who herself had been rejected by River House.) Unlike Streisand, after being rejected, Carey abandoned her uptown co-op search and bought a condo in Tribeca. Afterward, Streisand’s place languished on the market, eventually selling for $4 million — half of what Carey was said to have offered.

Other rich, famous people followed suit: They bought downtown condos and snubbed the kinds of buildings that had previously snubbed them. (Calvin Klein, rejected by the San Remo, went on to drop $20 million on a penthouse at Richard Meier’s One Perry on the West Side Highway.) Soon, uptown condos like 15 CPW and 220 CPS, built in the fashion of the best prewar co-ops but with central air, liberal subletting and pet policies, and a slew of amenities, made the blood sport of vying to buy in a co-op like 820 Fifth or 720 Park seem kind of silly. Today, the sprawling prewar apartments of buildings such as One Sutton Place and 740 Park often sit on the market for years, eventually selling at a steep discount and occasionally for less than they did 20 years ago. If high-profile co-op–board rejections are rare these days, it’s less because stuffy co-op boards have loosened up their social-register ways — though they have, at least a little, brokers say — but because far fewer people are trying to get in.

Many buildings have become notably more lenient in some regard, allowing pieds-à-terre, financing (there are holdouts, like 812 Park), trusts, pets, and new money. Summer work rules, which restrict construction to the weeks between Memorial Day and Labor Day, have been relaxed at many buildings to three, four, or six months or occasionally done away with altogether. Some even allow LLCs. “In the old days, co-op boards either knew someone who was applying or at least knew of them,” says a broker. That has changed, though things can still be pretty clubby. Antisemitism, once a prevalent issue, though hard to prove as boards don’t have to give a reason for passing on a candidate, is almost entirely a thing of the past. Not completely, however: A few brokers told me some East Side buildings still have reputations for turning down qualified Jewish buyers for spurious financial reasons who then go on to pass more rigorous boards (one buyer noted ruefully that they should have checked the names in the building’s reverse directory before making an offer). One broker says she avoids a few buildings, ones that “want you to show you’re a member of the Maidstone Club and didn’t inherit your money from your jeweler grandfather.” Not all that long ago, another broker told me, a board asked a couple if they “were the kind of Jews who have to walk upstairs on Saturdays.”

But for the most part, the buildings on Park and Fifth have moved closer to the board policies on Central Park West, where turndowns have been less categorical (i.e., no Hollywood types) and more a matter of personal preference. The San Remo was happy to take Dustin Hoffman and Demi Moore but found Madonna and Calvin Klein objectionable. John Lennon, Lauren Bacall, and Leonard Bernstein all called the Dakota home, but the board refused to take Cher and Billy Joel. Sean Lennon was rejected by 88 Central Park West, a few doors down from where he grew up; one broker describes the board there as “picky,” though certainly not celebrity averse: Paul Simon, Sting, Lorne Michaels, and Robert De Niro have lived there. In all, it’s a reminder that, at the end of the day, it comes down to the board members and whom they want living down the hall. Essentially, these days it’s not the old-guard, famously selective buildings that have the most difficult boards, brokers say, but the unpedigreed, sidestreet ones like 345 West 88th, the co-op that rejected Dunn. And young buyers with nontraditional wealth (like social-media money) face the stiffest odds, even when they apply to buildings without stuffy reputations. Even downtown buildings can get sniffy — one broker told me a client of his, a 30-year-old with hundreds of millions in assets, had been turned down from buying a $2 million Chelsea co-op. (Trust-fund kids are the exception to boards’ not liking young people, brokers say, but the catch is they need to know the parents. So a foreigner with family money gets the cold shoulder, while Susan’s daughter who went to Brearley receives a warm welcome.) Some co-op members seem to think having a hard-to-pass board will give them a reputation for exclusivity rather than erode their resale value. “The biggest joke is when I sell in a crappy building and the board gives me a problem,” says a broker. “Thinking that they are going to make themselves fancier by being difficult and persnickety is a big mistake. It might have been true in the past but not anymore. The buyers will just get a condo.”

In 1995, this magazine looked at the snobbiest apartment buildings in the city, the esteemed New Yorkers they’d snubbed, and the suspected reasons they were deemed unworthy. We revisited some of the most notoriously exclusive co-ops of the past to see how they have or haven’t changed.

River House, on the East River, was designed for residents to moor their boats outside. A few years later the FDR was built.

Photo: Compass

Known for being among the choosiest of the choosy buildings and the longtime home of Henry Kissinger, whose sprawling duplex, full of green upholstery and black candles — very Sister Parish — has yet to come on the market since his death. The building rejected Diane Keaton, Joan Crawford, and Gloria Vanderbilt, who sued over racial discrimination; she believed the turndown was due to her close (some thought romantic) relationship with Black singer Bobby Short. More recently, the French ambassador, looking to relocate the diplomatic residence from 740 Park, had his application nixed. But Turtle Bay is no longer particularly desirable, nor are the exceptionally large, often outdated apartments in the building, which not infrequently have warrens of maids’ rooms and stodgy last-century décor (5,000-square-foot-plus five-bedrooms can be had for as little as $5.25 million). In the past 15 years or so, the board has made something of an effort to ease up: Using the co-op’s name in real-estate listings, for one, is no longer forbidden. And in 2014, the board president told the New York Times it would review all applications within 45 days (in years gone by, co-ops would sometimes tacitly reject a buyer by just not ever getting back to them). It even let Uma Thurman in; she bought a $10 million apartment in 2013. “But you still need the right letters,” a broker told me. (They used to have to be handwritten, another told me, but that might have changed.) Today’s buyers are in line with the financiers and cultured trust-funders the building has always preferred. Most recently, a $3.3 million three-bedroom sold to a chairman of Sotheby’s fine-arts division.

A building where pretty much everyone is a billionaire, making it almost egalitarian, at least in one respect.

Photo: Corcoran

“740 has always been a money building,” says one broker. “They were sort of enlightened before the other buildings.” Enlightened meaning that pedigree and connections mattered less than being really, really rich. (At 720 Park, by contrast, the board “really cared if they knew you or knew of you.”) Financing is not permitted — meaning buyers must pay cash — and the liquidity requirements are rumored to be very high, in the hundreds of millions. Current residents include Stephen Schwarzman, who so loved the 35-room penthouse he bought from John D. Rockefeller Jr. that he once had the Park Avenue Armory transformed into a replica of it for his 60th-birthday party; Oaktree Capital’s Howard Marks, who set a $52.5 million co-op record in 2012; Millennium Management co-founder Izzy Englander, who set another co-op record ($71.3 million) in 2014 when he upgraded to an 18-room apartment (where he now seemingly lives alone); Lacey Tisch, who bought Steven Mnuchin’s 12-room place; and Ken Griffin, who bought David and Julia Koch’s apartment for $45 million this winter. “If you sign the contract, you kind of know you’re in,” another broker tells me. “Aside from one person, I think everyone buying in there is a billionaire or a billionaire’s child.” Other buildings where you mostly need to be “really, really rich,” according to one broker, are 834 Fifth and 960 Fifth. “You barely need to submit a financial statement because the truth of the matter is most really, really rich people know each other, know of each other, or know people who know each other.”

After years of being known as a top building that was pleasantly open-minded, one broker says 730 has become harder in recent years.

Photo: Compass

Over the years, the board of 730 Park developed a reputation for being nice. “Everyone was like, ‘Oh my God, it’s a really nice top building, and the board is flexible,’” says one broker. Designed by Lafayette A. Goldstone in 1928, it wasn’t a Candela (like 740 Park), a Carpenter (like 907 Fifth), or a Roth (like many Central Park West buildings), but, as at 740, the apartments are almost all duplexes, and the location, between 70th and 71st Streets, is second to none. When 60 Minutes host Mike Wallace was rejected by 770 Park, he bought here instead. “730 is a great family building,” a Tisch departing for the more rarefied realm of 740 told the Observer back in 2000. The board, laid-back socially, was known for somewhat stringent financial requirements: 30 years ago, the New York Times reported that buyers had to have a net worth of at least $50 million, the equivalent of more than $100 million today, and though the building now allows financing, it’s capped at 50 percent. Prices themselves aren’t so exclusive anymore, however: Real-estate investor Edward Minskoff’s apartment with Central Park views, asking $17.4 million when it listed in 2022, sold for just $7.4 million in 2024 to Michael Lorber, a real-estate agent and son of Howard Lorber, Douglas Elliman’s longtime CEO. And I’ve been told the board has become choosier of late. “Brokers would throw in their mediocre or subpar clients and the board would realize, Oh, now we’re stuck with this jerk,” says a broker.

One of the most selective buildings in the city. The longtime gatekeeper, Jayne Wrightsman, died several years ago, but brokers say it’s still a clubby situation.

Photo: Compass

This famously hard-to-get-into building was ruled over for decades, like much of New York society, by Jayne Wrightsman, wife of Oklahoma oil tycoon Charles Wrightsman and “arguably the most important patron in the modern history of the Met,” according to her obituary in the Times. Wrightsman moved into her 7,000-square-foot floor-through in the 1950s, filling it with French antiques, and stayed until her death in 2019 at age 99. The board turned down Ron Perelman (who was also rejected by 834 Fifth and 4 East 66th), Steve Wynn (rejected from 25 Sutton Place and 825 Fifth), and Fred Koch (apparently for being “very out-there gay,” as Wrightsman told corporate raider Asher Edelman, according to the Observer). The board was also responsible for one of the most high-profile smackdowns of recent years when it nixed Related CEO Jeff Blau’s $31 million bid to buy home-builder Ara Hovnanian’s fourth-floor apartment in 2009. Not even a call from (sitting) Mayor Mike Bloomberg could change Wrightsman’s mind. She may be gone, but, according to one broker, “it’s still a clubby situation. William Acquavella of Acquavella Galleries is board president, and a lot of the people who buy there are his clients.”

The board is reasonable and the building well-run, according to brokers. But that doesn’t mean they’ll take everyone. Madonna and Calvin Klein were both famously turned away.

Photo: Getty Images

Despite having rejected some boldfaced names, among them Calvin Klein and Madonna, the board here has never been overly picky — Madonna’s 1985 rejection, the Times noted, coincided with nude photos of her appearing in current issues of both Playboy and Penthouse. Celebrity residents have included Steven Spielberg, Demi Moore, Steve Martin, Dustin Hoffman, and Bono, among many others. Indeed, the board’s few celebrity turndowns seem to have more to do with how no one was too intimidated to submit an application. “I find the San Remo is actually a great example of a really well run building that gets very good buyers and is really reasonable,” says a broker. Many Central Park West buildings, always more accepting of entertainers and new money, have also modernized their rules lately to attract more buyers (or at least avoid their being an obvious turnoff). The Beresford, notes Lisa Lippman of Brown Harris Stevens, had a lot of units sitting on the market, but after allowing pieds-à-terre a few years ago and adjusting the summer work rules this year (by expanding the window in which renovations can happen), “a whole bunch of apartments sold for good numbers.” In March, a three-bedroom went for $6.62 million, slightly over the asking price (not a common occurrence in co-ops), and in 2023 architecture critic Paul Goldberger sold his four-bedroom there in a little under five months, which is considered brisk in the world of co-op sales.

The apartments are second to none, but they’re sprawling and families these days want to be closer to the private schools, brokers say. Many have also moved their primary residence to Palm Beach and are looking for more modest apartments with lower maintenance.

Photo: City Realty

Like River House, One Sutton Place South is farther east than is fashionable these days, with huge apartments that are a hard sell for families because they’re a hike to the private schools. Prices have slumped. This spring, a gorgeous ten-room apartment with East River views sold for $5.5 million, and a broker told me there was a substantial rebate to the buyer to replace the windows. Joanne Douglas, an associate broker at Douglas Elliman who is selling 4C, the same apartment a few floors up, and asking $4.95 million, tells me she has had a number of people come in, “and they love it, love it, love it. But their concern is renovations.” The board has made concessions: No more summer work rules, 50 percent financing is now allowed, and “it’s not like you need to be a member of the Union Club to get in anymore.” But while the board may be working to get with the times, the building is another matter. The cost of maintaining a really well staffed white-glove building for just 43 units is steep — 4C has an $18,500-a-month maintenance. And that money goes to a formal garden with a pretty fountain and a lot of staff, not swimming pools or pickleball courts. Also, brokers say, many of today’s wealthy Manhattan buyers have shifted their primary residence to Palm Beach. It used to be you’d have the small place in Florida and the big place in Manhattan. Now, that’s flipped, and as one broker put it, “people don’t want these gigantic apartments that have very high maintenance and aren’t close to a school.”

A big money building with big society names. As a broker once put it, you’re considered poor if you have less than $100 million. Indeed, it’s said to be an entry requirement, although it’s more like $200 million these days.

Photo: City Realty

The Rosario Candela building that the New York Times once described as “12 mansions built one on top of another” and that some considered the architect’s finest work is, as ever, a big-money building. As a broker once put it to the Observer, at 960 you’re considered poor if you have less than $100 million. (Indeed, back in 1995, brokers told the Times that the board preferred a net worth of $100 million, or $200 million in today’s dollars.) Reportedly, it still doesn’t allow financing and dislikes (but sometimes allows) trusts. It was considered to be among the very best of the “good buildings,” and its residents included Texas oil heiress and philanthropist Anne Hendricks Bass (whose apartment went for $53.5 million last year), prominent horse breeder and philanthropist Ned Evans, and Sunny von Bülow (whose husband Claus “had the good taste to sell his eighth-floor apartment” after being acquitted of attempted murder, as Steven Gaines once wrote). The $47 million apartment Aerin Lauder dumped her beautiful Park Avenue place for in 2019? In 960 Fifth, of course. As she told Elle Decor at the time, it had Central Park views and provenance: The previous owner was C. Douglas Dillon, JFK’s secretary of the Treasury, who “had wonderful taste and style” that she updated with the help of Annabelle Selldorf, who had impressed the family with her Neue Galerie renovation.

The board has historically preferred business and industry types vs. arts people. Recent buyers Christopher Flowers and Julia Koch, widow of David, have hewed to the tradition.

Photo: Google Maps

At this early 1920s James Carpenter co-op — one of the many buildings that rejected Ron Perelman back in the day — the board, ruled over by Bear Stearns CEO Ace Greenberg and Ezra Zilkha, an Iranian banker and Republican donor, has reportedly long gone for “business and industry types,” not “people from the arts.” (Socialites Sid and Mercedes Bass, tainted by scandal but with plenty of oil money, lived here together until their divorce in 2011.) Greenberg died in 2014 and Zilkha in 2019, but recent buyers still fit the bill. In 2020, financier J. Christopher Flowers paid $43 million for a floor-through here, and two years later, Julia Koch, widow of conservative macher and fossil-fuel tycoon David, left her longtime home at 740 Park for two floors here that had belonged to the late Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, paying $101 million for the penthouse and the floor beneath it, a co-op record. Apparently, it’s destined to be a lavish pied-à-terre: Koch told The Wall Street Journal she was selling her place at 740 Park because of all the time she was spending in Southampton and Palm Beach. Some units have languished in recent years: Socialite Shafi Roepers has been trying to sell her five-bedroom for the past decade. After initially listing it for $65 million in 2015, she switched brokers and dropped the price a number of times. It’s now asking $30 million.

Known for having a more accepting board — at least, for the world of elite co-ops — that doesn’t turn its nose up at new money. There just has to be a lot of it.

Photo: City Realty

Described by the Observer’s Max Abelson as “the most pedigreed building on the snobbiest street in the country’s most real-estate-obsessed city,” this is where Rupert Murdoch dropped a record-setting $44 million on Laurance Rockefeller’s triplex in 2005, which a broker once called “one of the five best apartments in New York.” (Wendi Deng got it in the divorce, and Murdoch was exiled to new construction in the Flatiron District.) Still, it’s not a board known to be overly stuck on buyers’ ancestral lines. As legendary broker Alice Mason once told Gaines in The Sky’s the Limit, 834 Fifth was known as a liberal building in terms of religion and new money despite being one of the best on the street. Serena Boardman got Len Blavatnik into Woody Johnson’s duplex in the co-op in 2015 after the Ukrainian billionaire was turned down by the boards of 740 Park and 927 Fifth. (The $77.5 million sale set a co-op record at the time.) 834 Fifth was also the first building to notch a sale above $1 million, in 1978. While some recent sales have been sluggish — Susan Gutfreund’s 12,000-square-foot duplex listed for $120 million in 2016 and finally sold for $53 million three years later, that seems more a symptom of delusional pricing than undesirability. One of the most recent transactions was the $21 million sale of Jack and Suzy Welch’s 5,000-square-foot duplex to financier John Vogelstein in 2022. No units are currently on the market.

Many boards now allow buyers to purchase in trusts, but LLCs — the preferred method of the ultra-wealthy — have long been a non-starter. The board here recently allowed it, however, as has 1040 Fifth. But brokers say that’s more about buildings with just a small number of residents who all know each other making exceptions for their friends rather than a sea change.

Photo: Compass

One of the biggest changes at elite co-ops is that most buildings now allow buyers to purchase in trusts. This may not seem radical, especially given that the buyers, and the intimate details of their finances and lives, are still revealed to the board in thick, 100-page-plus packages, but it was considered a sea change when boards finally made the concession to privacy and estate planning. Last winter, the ninth floor of 927 Fifth — the former home of Lazard CEO (and New York Magazine owner) Bruce Wasserstein, jeweler Harry Winston, and the red-tailed hawk Pale Male — went a step further and sold to a limited-liability company. This at one of the co-ops that rejected Babs! “The top buildings are wisely understanding that today’s buyer wants anonymity,” John Burger of Brown Harris Stevens, who represented the seller at 927 Fifth, told Curbed at the time. “It started with trust ownerships. Now we are starting to see some of the better buildings accept LLCs.” Another top-tier co-op that also (sometimes) accepts LLCs: 1040 Fifth, the former home of Jackie Kennedy. However, as Frederick Warburg Peters, the founder of Warburg Realty and now a broker at Brown Harris Stevens, pointed out back then, an occasional LLC purchase is less a sign of boards lightening up than of the cliquish nature of top-tier buildings, where exceptions can always be made for friends: “I would call it a reflection of the fact that these smaller superelite buildings kind of do whatever they want.”

If you have an interesting story about your NYC co-op that you’d like to share, please email tips@curbed.com or drop a comment below.