The present study found a lack of awareness concerning breast cancer screening among non-breast cancer women in China and identified several barriers to screening, including embarrassment, fear of radiation, and concerns about treatment costs, as well as some factors associated with unwillingness to undergo screening, such as identifying as “housewife” and having no medical insurance. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on KAP towards breast cancer screening in China that proposed a detailed discussion of economic burden. Our results differ from those reported in other populations and might be used to discuss and plan regional-specific policy changes or interventions, while data obtained on breast cancer screening might be helpful to reform policies, enhance screening rates, and promote early detection. Reducing economic and psychological barriers to breast cancer screening by expanding insurance reimbursement policies, conducting targeted public education campaigns, and offering communication and empathy training for healthcare providers may help improve participation rates and ultimately reduce the burden of breast cancer in China.

The majority of previously published studies have discussed the low rates of women undergoing breast cancer screening; however, some reported sufficient knowledge about breast cancer among respondents10,16. Recent KAP study conducted among women at high risk of breast cancer in China reports insufficient knowledge24while most recent meta-analysis pointed out lower awareness levels among Chinese and Asian women compared to women from other countries25. In line with above, the population of non-breast cancer women in this study that consisted of female Chinese nationals with a mean age of 29.79 ± 9.94 years, demonstrated poor knowledge regarding breast cancer diagnostic/screening methods. Although participants were primarily young women, the mean age in this study was slightly higher than average for this kind of KAP evaluation, mostly involving university students12,13,26. Part of this study population also included undergraduate students, but more than half of the respondents (55.91%) were employed, potentially covering a wider population. Additionally, the incidence of breast cancer increases with age, and this study explored specific perceptions among women over 40 in comparison to younger women, highlighting differences in awareness, attitudes, and practices related to breast cancer screening, providing valuable insights into how age influences perceptions of risk and screening behaviors. These differences may reflect the increasing integration of newer concepts, such as breast density and overdiagnosis, into recent health communication efforts, which younger women may encounter more frequently through digital platforms or recent education27. In contrast, older women may have had fewer opportunities to access or update such knowledge28. Future research should explore how different age groups access and interpret breast cancer screening information, and whether tailored communication strategies can help bridge these knowledge gaps.

One-third of the respondents lived in rural areas, which was associated with lower KAP scores in previous studies11,15. Likewise, in the current study urban or suburban residence was independently linked to better KAP scores. However, it is important to note that knowledge about certain issues was equally poor among urban, suburban, and rural residents. Notably, more than 50.0% of respondents were unaware that Asian ancestry is related to a higher density of breast tissue, potentially impacting the sensitivity and accuracy of mammography29. In contrast, women aged over 40 showed even lower awareness about ultrasound and breast density but were more willing to consider US as a screening option, partly due to its lower cost. The US has been recently suggested as a feasible alternative to mammography for breast cancer screening, especially for women with dense breasts30a topic that requires further discussion since most women are unaware of it. Finally, more than half of participants expressed concern that the radiation would cause them harm during the screening; participants unwilling to undergo screening (n = 37) more often expressed the belief that mammography is inherently radioactive and painful. This may stem, in part, from general health education campaigns that emphasize the importance of protecting oneself from excessive or unnecessary radiation, which, while well-intentioned, may contribute to public apprehension even in the context of low-dose diagnostic procedures such as mammography31. According to the recent comprehensive benefit to risk analysis32the radiation dose and associated risk for a single examination is dependent upon breast density; however, with 65 induced cancers and 8 deaths per 100,000 women over a screening lifetime, this results in 62:1 ratio of lives saved to deaths from induced cancer. Since identifying the best breast cancer screening technique will undoubtedly improve cancer management, gaps detected in the knowledge dimension should be considered during future educational interventions.

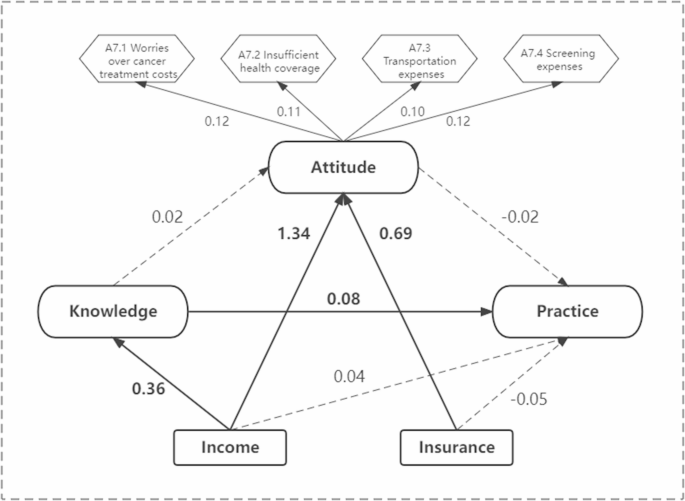

Previous studies used logistic regression analysis, finding that lack of awareness regarding mammograms was significantly associated with age and profession, years of experience, geographic region, and personal history of breast cancer33,34,35. Education also influenced breast cancer screening practice21,33. Abeje et al.21 discussed economic factors in their study, where women with a high level of income were about 3 times more likely to be aware of breast cancer screening methods, while Alenezi et al. identified low income as one of the factors associated with the low uptake of mammogram screening programs in33. Begum et al.35 and de Oliveira et al.11 reported expenditure concerns as the leading cause for not seeking medical advice for the prevention of breast cancer. In the present study, higher income was associated with better KAP scores, while the influence of knowledge on attitude and practice was notably less strong. Moreover, identifying as “housewife” and having no medical insurance were significantly associated with unwillingness to undergo breast cancer screening, outlining the most vulnerable participants. It may at least partly explain the lack of obvious progress in awareness regarding breast cancer over time, reported by recent cumulative meta-analysis, despite ongoing educational efforts25. Present study demonstrated that residence and monthly income were predictors of higher KAP scores. Worry regarding treatment costs upon detection of breast cancer on screening was identified as one of the new economic barriers, which is comparable to the worry about the cost of screening itself; moreover, in the subgroup of women aged over 40 years old this concern affected practice scores even more significantly. These findings complement a previously published systematic review of English-language KAP studies, which identified one key reason for avoiding regular screening as an overly optimistic belief in personal health and low perceived risk of breast cancer15and suggest that in Chinese women educational interventions focusing on the risk of the disease might not be enough to promote timely breast cancer screening. Moreover, our findings suggest that women in different age groups may face unique challenges and concerns, which should be taken into account when designing future efforts to promote early detection and improve screening participation.

Although health education might not be enough to overcome the economic burden of breast cancer screening, some steps in this direction were proven to be effective. Specifically, educational model-based interventions (Health belief model, Health Promotion Model) have been shown to promote self-care and create a foundation for improving breast cancer screening behavior36. Empowering women in the healthcare profession also positively impact the attitudes and beliefs of female patients in the hospital and the general public18. Finally, in the present study, only 30.53% of respondents have chosen mammography compared to other options, while 53.29% were more willing to undergo US screening. Based on that, the introduction of US screening as the less expensive alternative might ease some worries regarding the screening cost, as well as the widespread fear of radiation exposure during mammography. Thus, future policies should focus on accessibility (such as introducing US), financial support, and awareness. For instance, culturally tailored media campaigns using social media and community health workers could address misconceptions and promote awareness37. Incorporating modules on empathetic communication and patient counseling into continuing education for healthcare professionals may foster more supportive screening environments and reduce anxiety among participants38. Additionally, employer and community-based initiatives, along with a national screening registry, can help track progress and refine policies for better long-term outcomes39.

Study limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, the study was conducted in China, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other countries and cultures. Moreover, the governmental breast cancer screening program in China is directed at women older than 45 6, so the discussed economic burden may not apply to countries where breast cancer screening is free of cost for all ages. Meanwhile, although formal screening in China begins at age 45, younger women were included because risk-stratified guidelines permit earlier screening, incidence is rising in this group, and they face economic barriers to accessing care. Characterizing their profiles thus informs future programme expansion and equitable screening strategies. Although the inclusion of respondents younger than 45 may have introduced a degree of generalisation bias, participants were not restricted by age, which allowed to capture a wider range of perspectives across age groups. Additionally, while age-related differences in knowledge were observed, the study did not assess participants’ prior exposure to breast cancer-related information, such as via traditional media or digital platforms, which may have contributed to these differences. Secondly, using a self-administered questionnaire may have introduced response bias, which could affect the accuracy of the results. Selection bias also could not be completely excluded, as participants who volunteer for KAP studies might differ systematically from the general population in terms of knowledge, lifestyle, or other factors. Future studies with broader and more diverse participant groups are necessary to confirm and expand upon our findings. Finally, it was not possible to check whether or not respondents who answered positively would undergo timely screening; better results might be explained by social bias40 when respondents gave the answer that was expected according to the nature of the study. As we did not assess the impact of interventions aimed at increasing breast cancer screening rates, whether the proposed targeted efforts would be effective should be further investigated in the future.

There is a strong need to improve knowledge, attitude, and practice towards breast cancer screening among women in China; barriers such as lack of knowledge regarding the methodology and inadequate risk assessment should be addressed, especially among women from rural areas and with low monthly income. Breast cancer screening in China should be improved by focusing on identified barriers through educational initiatives and awareness campaigns that could help to promote screening and address concerns while promoting private and comfortable examination facilities and respectful care. Policy changes or interventions, such as subsidies or insurance coverage, may help address treatment cost-related issues.