Editors’ note: This story first appeared in New York’s issue of September 30, 1968. We’re republishing it today as part of Curbed’s “Tales From the Co-op” week.

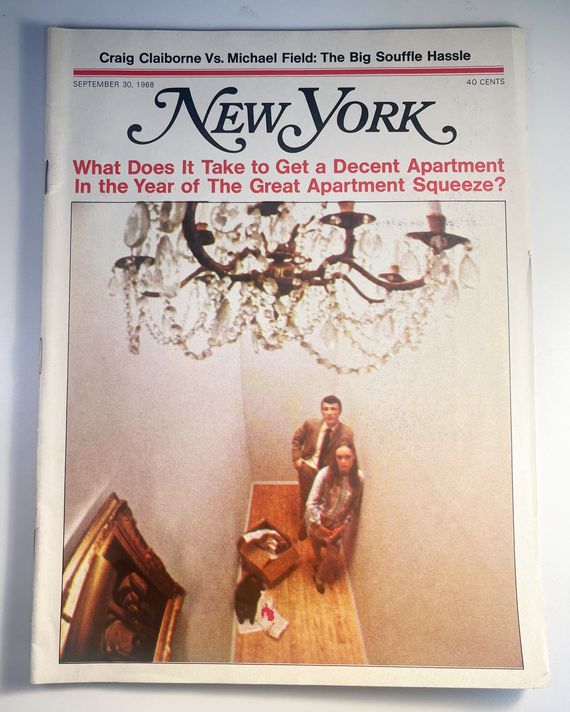

Finding and renting a desirable apartment in New York today requires such concessions of conscience, income, and pride that surgeons have postponed operations, housewives have gone back to work, hippies have cut their hair, and families have destroyed their pets. In Manhattan, where competition for the smallest, darkest, highest walk-up is most intense, prospective tenants find the search for an apartment the center of their lives. It dominates their conversation. It alters their sex habits. Currently, a whole generation of young career girls, forced into double and triple occupancy, have given up any hope of secrecy in their affairs. No one is spared the agony of the search or the disappointment of their find. John Hay Whitney, one of America’s wealthiest and most influential men, spent years piecing together a row of three small East 63rd Street townhouses for his own use. What he finally wound up with was $1 million worth of renovated elegance facing directly on a major artery for the bumper-to-bumper traffic honking its way off the Queensborough Bridge. Thousands of middle-income tenants, unnerved by months of fruitless searching, settle for fewer rooms than they need and more rent than they can afford. Young couples scour the obituary pages as well as apartment listings for possible leads. Doormen, superintendents, and moving men are paid off for their tips on upcoming vacancies, and prospective tenants soon find that they must pay far beyond the old New York budget rule of 25 percent of their income for housing.

Modesty, gentility, and protocol have no place in the apartment grope. When a well-known historical novelist died recently, a stockbroker friend called the author’s landlord the next day in order to rent his deceased friend’s nine-room Fifth Avenue flat. He was too late. The author’s physician, moments after pronouncing his patient dead, wrote a check for the apartment. Some desperate prospective tenants have even been driven to burglarizing the offices of the New Jersey printer of The Village Voice in order to get a day’s head start on that weekly’s apartment listings. And the New York Times, after repeated complaints from landlords and agents, now keeps a guard on duty to make sure its employees do not sneak advance copies of the Sunday real-estate section out of the building. This month, with the leases on 700,000 uncontrolled apartments coming due, an already unbearable situation has suddenly worsened. Thirty to 100 percent increases are being asked for apartments built since 1947 and therefore unaffected by rent-control laws. Hundreds of thousands of tenants, those men and women who moved into the brand-new high-rise balcony-slumbernook-and-dining-alcove buildings three and four years ago, are finding this month that they cannot afford their own apartments.

“People are expendable to me,” Selena Goudeau, a Greenwich Village real-estate agent, said. “There are simply many more clients than apartments, and I can only fill one out of every 100 applicants. These people come in here,” Miss Goudeau continued, waving her arm toward a row of men and women who shifted nervously on a narrow wooden bench less than five feet away, “’and they’re desperate. They need apartments. They want to live in the Village. They’re lonely. They come in here begging. They come in crying.”

Because there was no ashtray available, one of Miss Goudeau’s prospective clients put his cigarette out on the sole of his shoe and then, his eyes darting about her Sheridan Square office for someplace to throw it, decided on his own pocket. Miss Goudeau is one of 69,705 real-estate brokers and salesmen licensed by New York State. The fact that she is working in Manhattan enables her to place an average of 40 to 50 grateful clients a month. Her fee, which is usually paid by the tenants, is a $100 minimum or 10 percent of a year’s rent.

“Landlords come to us,” Miss Goudeau continued, “because it doesn’t cost them anything. No ads in the paper, no weeding out of hippies.” She snapped a fast look at her prospective clients who fidgeted in silence, their eyes on the floor. “Landlords want a feeling of stability. They don’t like long hair. They don’t want all-night parties. Pets make a mess. Musicians make noise. Some tenants even try to lie when they come in. Some even cut their hair. A few lucky people find apartments. Not everyone, but a few. Some have been so happy they call me up and want to send me all of their friends. Gawhd!” she groaned. “I try to discourage that.”

The reasons for Manhattan’s current apartment grope are many. Of the city’s 2.1 million private apartments about 1.4 million are under rent control, and the 4 million New Yorkers who live in them rarely move. It is a situation that has kept families in neighborhoods they no longer like, old couples in buildings filled with party girls, and has fostered a war of nerves and services between tenants and landlords. Owners claim there is no profit in rent-controlled buildings, though they are guaranteed by law a 6 percent return on the assessed value of their property, plus 2 percent on the value of their building for depreciation. Their tenants, most of whom are the only remaining middle-income families Manhattan has, insist they could not possibly afford the $150-a-room rent comparable apartments might cost. As a result of the impasse, landlords have literally abandoned and left to decay 12,000 buildings with 350,000 rent-controlled apartments around the city, and the middle class continues its exodus to the suburbs in search of better housing.

Of the 700,000 non-rent-controlled apartments built after 1947, the greatest number were erected just before 1963. At that time landlords purposely overbuilt to avoid complying with an expensive new zoning law, which went into effect in 1963 and raised the standards for open space and light. As a result, they glutted the market with new apartments about five years ago and gave all kinds of concessions — including one and two months’ free rent — to anyone willing to sign two- and three-year leases. Since that building boom, there has been almost no new apartment building in Manhattan, and what was a tenants’ market five years ago has suddenly turned into a landlords’ market today. High-, middle-, and low-cost rents are all being increased. Studio apartments that were $180 are going up to $225 when lease renewals come up this month. Two-bedroom apartments in the East 70s are being raised from $475 a month to $590. Small, cramped three-bedroom apartments are being raised from $520 to $625 a month.

The solid pockets of middle-class rentals like Stuyvesant Town’s 8,755 rent-controlled apartments will be raised, and it will not be their first increase. Since the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company first built the two-bedroom apartments in 1947, rents have more than doubled. An apartment that rented for as little as $62 a month 20 years ago now rents for between $138 and $173.50 a month. As of October 1, 950 of Peter Cooper Village’s one-bedroom apartments will be increased, in some cases as much as $40 a month. With rent increases expected to continue, more and more real-estate executives are beginning to admit quietly that there is simply no place for the middle class or the poor on the Island of Manhattan.

“The historical system of private ownership is just not working,” Donald H. Elliott, chairman of the City Planning Commission, said. As resident-owners dwindle (the old husband-and-wife landlord teams who watched after their building and its maintenance), the speculators and amateur landlords who are taking over are seldom able or even willing to keep buildings in good repair. As a result, there are 800,000 deteriorated apartments in New York today. New residential building, especially in Manhattan, is considered far too costly, and builders prefer to concentrate on office structures. The city’s Black and Puerto Rican residents, meanwhile, who make up 28 percent of the city’s population and have a median income of less than $3,500 a year, simply cannot afford the $70 to $110 per room of privately built housing. Low-cost housing, while it is encouraged by the city and the state, is not profitable enough to attract builders. There are currently 525,000 people in low-cost housing in the city paying about $18 a room per month, and there is a list of 135,000 people waiting to get in. Landlords point out that between 25 percent and 33 percent of every rent dollar they collect goes to taxes and that to invest in low- and even middle-income housing is simply not feasible. “Anyone can get the 6 percent profit we’re allowed by investing in bonds,” one builder said. “And that’s without headaches.”

With very few exceptions, low-rent buildings are run down, services are almost impossible to obtain, and except for the fact that New Yorkers have been so brutalized by their living conditions, such housing would be uninhabitable. A recent arrival from Waco, Texas, found himself paying $145 a month for a single unfurnished room in a dilapidated tenement in Washington Heights. In Waco, that rent could have bought him a two-bedroom, air-conditioned apartment with plenty of light, an open courtyard and a swimming pool.

“The New York apartments I’ve seen are dark and close,” he said. “You can smell the food people are cooking in the halls, and when you look out your window, you can see people seated at kitchen tables eating. And the paint is so bad. Everything has been painted so many times it’s lumpy. Nothing fits. Cabinet doors don’t close and windows don’t open. The thing l couldn’t get used to at first was always feeling someone’s breath on you. You can’t get away from the sounds of other people’s lives. You hear their noises in the night. Sometimes you hear screams, and when you look out there’s somebody looking out his window at you.”

“A family man earning $35,000 a year has it tough living in Manhattan,” Louis Smadbeck, president of William H. White, Inc., one of the city’s largest realty companies, said. “The answer for men like that is the cooperative, but two-bedroom co-ops are unavailable for less than $35,000 cash, and who do we know who makes $35,000 a year has $35,000 in cash? The need therefore is for some kind of state subsidization of mortgages in the financing of co-ops. Today, conventional banks will not give mortgages on co-ops because they are geared to hold equity in a building, not stock in a cooperative.”

Smadbeck feels that many landlords are so anxious to get out of rent-controlled buildings that tenants could buy their apartments for as little as $200 and $300 a room and, by forming a cooperative, get a mortgage to raise enough cash to make capital improvements on the buildings.

“There doesn’t seem to be any other solution,” he continued. “Rent controls create antagonisms between tenants and landlords that are irreparable. When it comes to someone’s apartment, for heaven’s sake, he at least shouldn’t have to worry about painting and electric wiring. For the lower-middle-income people, cooperatives could be arranged through the responsibility of the state. I’m not asking the state to make a bad investment but just to assist banks by insuring investments for 90 percent value on mortgages instead of two-thirds as is the law now. The alter- native is an unreal island of millionaires.”

Smadbeck’s alternative may be only a slight exaggeration. A series of interviews with some of the city’s leading brokers revealed what they consider “conservative” estimates of the income needed by a man and his wife and two children to live in various sections of Manhattan.

On the East Side, between 59th and 96th Streets and along Fifth and Park Avenues, a minimum annual income of $125,000 is required, they say. While three-bedroom apartments rent for as much as $1,500 and $2,000 a month, many of the buildings along those avenues are cooperatives selling for $150,000 with maintenance of $1,000 a month. In the same general area, there are presently 354 small townhouses, most of which are occupied by single families. The current market value of East Side townhouses, some as narrow as 13 feet, is estimated at between $275,000 and $500,000. Brownstones that were $125,000 ten years ago have doubled in value today.

Along Central Park West, West End Avenue, and Riverside Drive, the Realtors agreed that $75,000 a year would be the minimum required for a family if they did not occupy a rent-controlled apartment or a cooperative. The West Side though, they say, is in the greatest flux. The large, airy apartments in big buildings are beginning to go cooperative, and many of the brownstones, long deteriorating on the side streets, are being restored by families through low-cost urban-renewal loans.

To live along lower Fifth Avenue or from 9th to 13th Streets between University Place and Sixth Avenue, the realty people agreed, $60,000 would be sufficient.

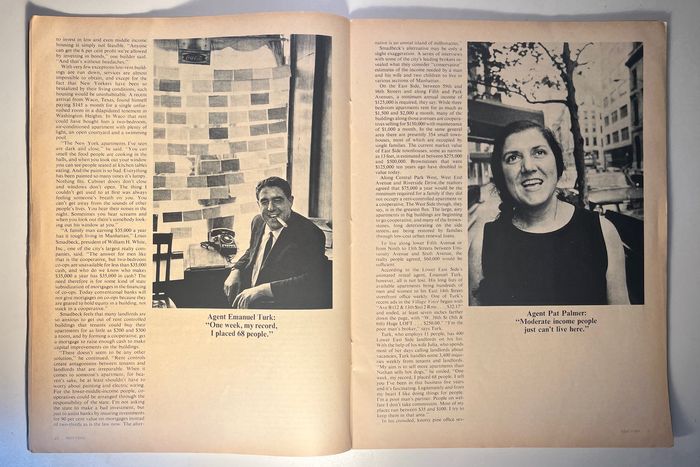

According to the Lower East Side’s animated rental agent, Emanuel Turk, however, all is not lost. His long lists of available apartments bring hundreds of men and women to his East 14th Street storefront office weekly. One of Turk’s recent ads in the Village Voice began with “Ave B (12 & 13th Sts) 2 Rms …. $32.17” and ended, at least seven inches farther down the page, with “W. 38th St (5th & 6th) Huge LOFT … $250.00.” “I’m the poor man’s broker,” says Turk.

Turk, who employs 11 people, has 400 Lower East Side landlords on his list. With the help of his wife, Julia, who spends most of her days calling landlords about vacancies, Turk handles some 3,400 inquiries weekly from tenants and landlords. “‘My aim is to sell more apartments than Nathan sells hot dogs,” he smiled. “One week, my record, I placed 68 people. l tell you I’ve been in this business five years and it’s fascinating. Legitimately and from my heart I like doing things for people. l’m a poor man’s partner. People on welfare I don’t take commission. Most of my places run between $35 and $100. I try to keep them in that area.”

In his crowded, knotty-pine office, several young men and women sit at desks filling out forms. Turk, who stands about six feet tall and weighs well over 200 pounds — “I just lost 86 pounds” — moved with surprising grace through a jumble of desks, chairs, and people. Snatching a fist full of keys from a wagon wheel that decorates one wall, he began jiggling them.

“Keys are the key to my business,” he beamed. “I like to say we have the keys to all apartments.” Suddenly he rose to his toes and shouted to the room full of clients: “Anyone waiting for a salesman? Anyone?” Then spotting a thin, lankhaired young lady he bowed, and pointing to one of the occupied desks, said, “Mr. Calabrese, my associate and friend. will take care of you.”

Turk explained that the apartments he advertises for $35 a month are all rent-controlled and are usually on the Lower East Side. “They call it the East Village, even over by Avenue D.” They are all five- and six-story walk-ups with toilets in the hall, the type of tenement it was forbidden to build after 1901.

E. Turk’s opposite number in Manhattan would have to be Pat Palmer, who specializes in expensive apartments on the city’s East Side. Dealing in cooperatives, townhouses, and luxury apartments, Pat Palmer works out of her own townhouse (it used to be the William Randolph Hearst residence) at 22 East 67th Street. Unlike her clients, Miss Palmer is unimposing, a dark-haired woman in her late 30s who is constantly amazed at the fact that she is often the biggest celebrity at a party. At gatherings with film stars, theater people, and television personalities, many of whom she has found apartments for, she is usually the center of attraction.

“It’s unbelievable, but I’m overwhelmed at parties,” she confesses, opening her eyes wide and pursing her mouth. “Everyone has something to discuss about apartments. People seem fascinated by apartments and who lives in them. Everyone seems to have one building or one apartment that has caught his eye. ‘Who’s in that one?’ they’ll ask, or ‘How much would such and such a place cost?’ That sort of thing. Everyone likes to hear stories like the one of the man who lives in a chicken-coop house on top of a townhouse in the 60s off Fifth Avenue. He rents the chicken coop for $125 a month, and it has no heat and no sink. When l heard about it, I felt so sorry for the guy that I carried a sink over to him myself and gave it to him.”

Recently she sat at her desk, a kerchief still knotted over her head 30 minutes after she had come indoors, trying to mediate an argument between two men over $400. One had, just moments before, sold the other a $265,000 cooperative apartment. “Can you imagine,” Miss Palmer said after both men stormed out of her office, “quibbling over $400 after a $265,000 deal?”

Pat Palmer claims that nine out of ten residents of the expensive East Side apartments in which she deals are from out of town.

“Most of them are on Wall Street or they’re investment bankers or in business,” she explained, “but they’re big. I mean they’re really big men. Judging by the kinds of places they take, they must earn at least $75,000 to $125,000 a year. I’m not talking about a few hundred people, remember. I’m talking about thousands and thousands of people. All those men and women who fill the apartments along Fifth Avenue from the Plaza to East 100th Street. And all of them stacked up along all those side streets. That’s a lot of very, very rich people.

“Moderate-income people just can’t live here. We used to have a few inexpensive, rent-controlled apartments, but most of them have been torn down and replaced by large apartments or co-ops. These new buildings are bringing in between $275 and $325 for one-and-a-half-room studios, and a two-bedroom apartment — that’s a small two-bedroom — brings $650. None of these buildings have fireplaces or gardens either. These are the nine-foot ceiling apartments lacking in what we call charm.

“The same places, the same amount of room, that is, with charm,” she continued, smiling, “bring almost double the rental. Right now I have a nice little two-bedroom, two-bath apartment in a new building. It has a doorman and an elevator man and a living room that measures 20 by 12, and it is a real bargain at $650 a month. At the same time I have a floor-through in a townhouse with only one bedroom and a tiny den, a living room, and small dining area and terrace, and it costs $1,000 a month. The townhouse costs almost double because its ceilings are high, it has floor-to-ceiling French windows, fireplaces in the bedroom and living room, and a terrace garden.”

Bernard Walpin, who concentrates on the less prestigious and less costly apartments of Manhattan’s West Side, insists, “Take away the East Side’s chichi and what have you got? Pickup bars!” Walpin is a short man who wears thick, recently acquired sideburns and has a rapid-fire delivery that overrides replies. “The West Side is becoming the place for New Yorkers with families,” Walpin began. “More and more people are moving from the East Side to the West Side every year. They’re almost all professional people, and there has been a push of creative people too. There is a tremendous discrepancy between the people who lived here and those who are moving in. Living on the West Side ten years ago you could have had a six-room apartment for $200. Today at least double that would be a bargain.

“The West Side is also the best bargain in town for two-bedroom apartments. Lots of them are still under rent control because there is so very little turnover. Every time a new lease is signed on a rent-controlled apartment, the owner has the right to raise the rent 15 percent. On the West Side, nobody ever left their two-bedroom apartments, and so today they are still pretty reasonable when you can find them.”

Aside from E. Turk and his bargains, little hope is held out for the middle-income ($15,000 to $20,000 a year) people, career girls who do not want roommates, and couples with more than one drawer-size infant. Lewis Sarasy, a broker specializing in Greenwich Village houses, recently advertised a small Village townhouse. The building admittedly was small, the ad explained, but could be ideal for two people just starting out. Its price was listed as $125,000, and when a curious ad reader called the next day, he learned that Sarasy had already received a number of serious offers.

Exaggerated costs are matched by exaggerated descriptions, and no small part of mastering the city’s apartment grope is mastering the cryptic language of rental ads. Learning that the word “Jr.” means very small, “stall shower” means no bathtub, and that many landlords have upgraded fire escapes to balconies and balconies to terraces can save many unnecessary cab fares.

“Village. Parlor Flr Thru. Lg. bdrm. Lvg rm & effc kitch,” for instance, turned out to be at First Avenue and East 11th Street — many blocks from Greenwich Village. The parlor-floor designation turned out to be the second floor since the agent arbitrarily lowered every one of the building’s floors by one level. The building had a high stoop and over the entrance a metal address tag which read “Ground Floor.” The only connection between the bedroom in the rear and the living room in the front of the apartment was a tiny kitchen-hallway. Stove, refrigerator, sink, and closets lined two sides of the connecting passageway making all of the efficiency in that kitchen incumbent upon the tenant. The bathroom in the apartment, as in most floor-throughs, was off the bedroom in the rear of the flat, meaning guests had to tramp through the kitchen and bedroom in order to get to it.

Yet, at 2:30 every Wednesday afternoon, hundreds of people continue to fill Sheridan Square waiting for the first issue of The Village Voice. Tempers are short and telephones are rare. Veteran apartment gropers know enough to commandeer every working telephone booth in the area using friends who listen to dial tones and weather reports for an hour before the newspapers arrive. When the newspapers do go on sale, the homeless run blindly across Sheridan Square’s seven-street intersection without a glance at traffic. Automobile brakes screech. Drivers curse and snarl. Men and women race toward their captive phone booths, urged on by their colleagues who, stretching like first-basemen, reach as far out of the booths as they can while holding onto the receivers. Cars, motor-scooters and bicycles roar away from the curbs, and another week of the great apartment grope has begun.

Related