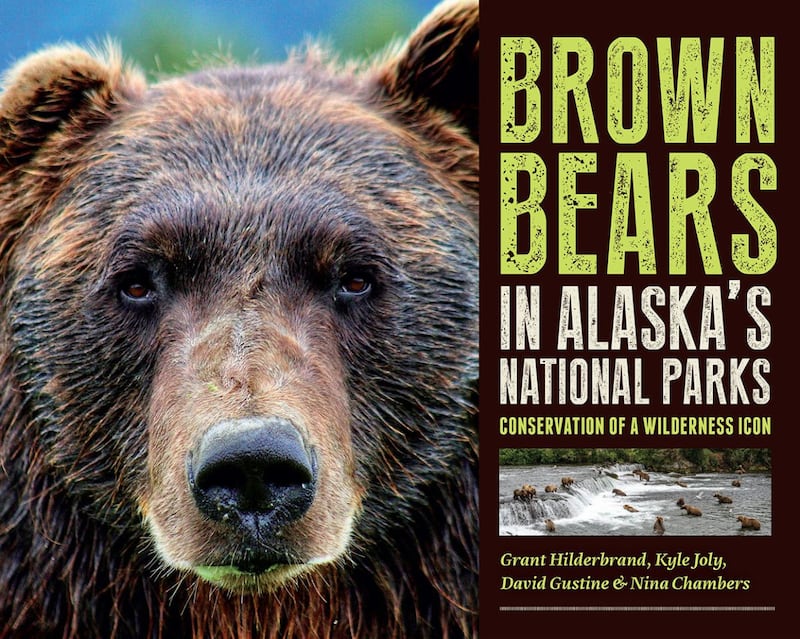

“Brown Bears in Alaska’s National Parks: Conservation of a Wilderness Icon,” edited by Grant V. Hilderbrand, Kyle Joly, David D. Gustine, and Nina Chambers

“Brown Bears in Alaska’s National Parks: Conservation of a Wilderness Icon,” edited by Grant V. Hilderbrand, Kyle Joly, David D. Gustine, and Nina Chambers

“Brown Bears in Alaska’s National Parks: Conservation of a Wilderness Icon”

Edited by Grant V. Hilderbrand, Kyle Joly, David D. Gustine, and Nina Chambers; University of Alaska Press (University Press of Colorado), 2025; 251 pages; $95. hardcover, $29.95 paper, $23.95 ebook.

There are many books about bears, but this new one, with contributions from 35 of the most knowledgeable collaborating bear experts from Alaska’s national parks, is an outstanding, very attractive and very readable compendium of the most current science and management issues concerning brown bears in our parks.

Brown bear, as most Alaskans know, is the accepted name for Ursus arctos, the species otherwise known as the coastal brown bear; grizzly, away from the coast; and Kodiak bear, on Kodiak Island. Aside from those geographical differences, the authors make clear that there are considerable differences among bears within regions and as individuals. There is no “average bear” among the 30,000 or so brown bears thought to live in Alaska today.

The book begins with a chapter about concepts of wildlife conservation, the conservation mission of the National Park Service, bear management in Alaska and what it means to “ask the right questions.” That’s followed by a very informative chapter about bears and humans, including examples of the immense cultural significance of bears to Alaska’s Indigenous people.

Additional chapters cover how bears live in their world, the challenge of human-bear coexistence and the question of how well bears are adapting to the modern, warming world. In terms of coexistence, the authors point out the dangers of food-conditioned bears and suggest tools and advice for interactions. They also provide a very handy chart that summarizes bear-viewing opportunities in various parks and preserves, with information about the kinds of experiences involved, distance regulations and recommended best practices.

Bear viewing, the authors argue, provides conservation benefits by creating advocates of those motivated by their experiences. Bear hunting, for both subsistence and sport, is also recognized as an important activity on most national park lands in Alaska, although practices allowed on state lands — such as predator control and bear baiting — are not, to support natural processes and behaviors.

Climate change is expected to affect bears as they deal with heat, shorter winters, changes in prey and wildfire. Bears are, however, highly adaptable; future studies will track their abilities to change behaviors as their environments change.

One of the most fascinating chapters, by biometrician Joshua H. Schmidt, addresses how techniques for estimating bear populations are evolving and improving. Schmidt details the various ways in which surveys are designed and conducted. The invasive and costly practice of radio-collaring bears is now being supplemented or replaced by DNA sampling from hair snagging, the practice of sight-resighting and applying existing survey data to new surveys.

Later chapters are specific to bears in particular national parks — Glacier Bay, Denali, Gates of the Arctic, Katmai and Lake Clark. These chapters, written by teams of biologists with extensive knowledge of the individual parks and their bears, include detailed maps and sections on history, habitats, bear populations and habits, human visitation and bear viewing, management challenges, studies that have been conducted or are underway, and future study needs. Again, attention is paid to the Indigenous people whose homes were or are within park boundaries and how they’ve lived alongside their bear neighbors. These chapters make it possible to appreciate the uniqueness of each park, the bears within them, and the opportunities for experiencing bears in their home places.

For example, in the Katmai chapter, readers will learn about the establishment of Brooks Camp as a fishing lodge in 1950 — and that at that time few bears frequented the Brooks River falls because they were viewed as competitors and heavily hunted. Today, upwards of 30 bears may be seen at one time fishing at the falls. Almost 16,000 people visit Brooks Camp in a season, and another 7,000 visit the Katmai coast by boat and plane. Today there are multiple viewing platforms at Brooks Camp, orientation talks by rangers, and an electric fence around the campground. There are also concerns about the increasing amount of human visitation, the quality of experience, and safety.

Each of the book’s 13 chapters ends with extensive notes identifying the scientific papers and other sources relied on. The bibliography at the end provides full details for locating all the references. High-quality color photographs throughout, from National Park sources, show bears being bears and, in some cases, researchers collecting data.

“Brown Bears in Alaska’s National Parks” belongs on the shelves of everyone, in Alaska and beyond, with an interest in wildlife, parks, or conservation. It would also be an excellent gift for any young person interested in wildlife or a career working in one of our richly inhabited national parks. As long as research funding exists, opportunities for adding to what we know about bears — in places of tremendous beauty, ecological importance, adventure, and mystery — are nearly boundless.

As the authors of the chapter on variation and resilience put it, “It has been said that the best days of a scientist’s career are when they are surprised by their findings. During these recent studies, we had many ‘best days.’ ”

[Book review: A journey through polar science helps explain our living world and its future]

[Homer author’s new book puts facts and stories about Alaska glaciers at your fingertips]