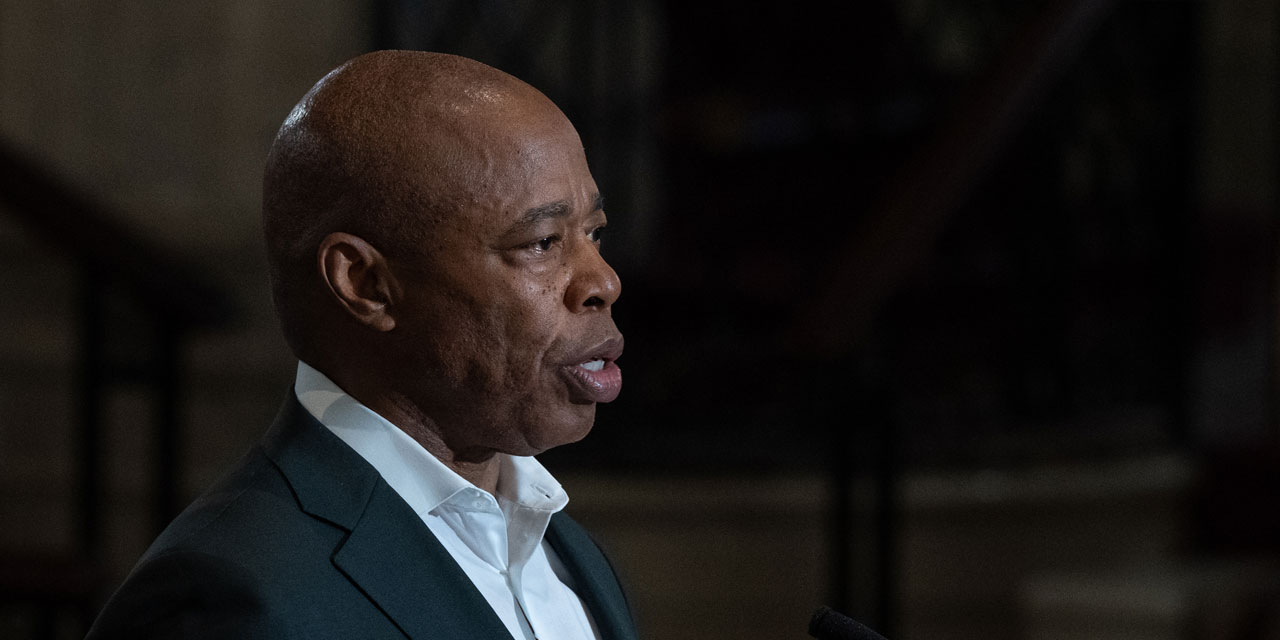

On Thursday, New York City mayor Eric Adams proposed the Compassionate Interventions Act, allowing doctors and judges to order involuntary treatment for people addicted to drugs or alcohol who pose a danger to themselves or others. “We must help those struggling finally get treatment, whether they recognize the need for it or not,” Adams said at a Manhattan Institute event. “Addiction doesn’t just harm individual users; it tears apart lives, families, and entire communities, and we must change the system to keep all New Yorkers safer.”

Adams’s plan is a welcome step. He understands that addiction, violence, and public disorder are closely linked, and that the city must address them together. Paired with more funding for rehabilitation, the measure could significantly reduce public drug use.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Adams’s move follows a persistent struggle with public drug use in New York. Hot spots like Washington Square Park and the Hub in the Bronx have been overtaken by encampments where people shoot up in front of tourists and children. Last year, the city saw over 2,100 overdose deaths. That’s part of why New Yorkers overwhelmingly support the NYPD’s efforts to crack down on drug use and remove users from the subway.

Despite these issues, many activists will argue that forcing addicts into involuntary commitment and treatment—more commonly reserved for the severely mentally ill—is an abomination. Yet, such laws are hardly rare: 36 states and the District of Columbia already allow involuntary commitment for addicts.

In most states, a family member or doctor can petition a court temporarily to detain addicts, who are then sent for evaluation. If a medical professional determines a user poses a clear and significant threat to himself or others, he can ask a court to mandate treatment. As with the mentally ill, the treatment can require inpatient care—weeks or months in a rehabilitation facility—or outpatient care, with mandated participation in services supervised by a medical professional. Adams’s plan would follow a similar model, allowing clinicians to refer people for treatment if they show signs of dangerous drug addiction and empowering judges to mandate treatment if they refuse to go voluntarily.

Addicts share many traits with individuals with severe mental illness, who are also often committed. Both are frequently unaware of the extent of their problem, often refuse treatment unless compelled, and, most importantly, often harm themselves and those around them.

One key difference is that using drugs, unlike being schizophrenic or bipolar, is a choice. But addiction makes stopping neither easy nor simple. Such individuals can benefit from a firm outside hand requiring treatment, even if they resist it at the time.

Though no simple treatment is available for addiction, several mandatory rehabilitation programs have proved successful, most resulting from court orders for drug or alcohol-related crimes. The 24/7 program requires people with an alcohol problem who get a DUI to undergo at least daily sobriety monitoring and face “swift and certain consequences,” such as brief jail time, if they fail. Such initiatives have been shown to reduce alcohol abuse.

Drug courts provide addicts who committed a crime with alternatives to jail or prison if they follow a mandated treatment regime. Evaluations vary, but most show at least some reduction in substance abuse and reoffending. One recent study found that participation reduced drug and alcohol abuse by 7 percentage points.

While it can help, increased compulsory treatment will only work if it’s accompanied with more resources for inpatient treatment and supervision. Nationally, 96 percent of beds designated for addicts are already full. But given that overdoses remain the leading cause of death for young people in the U.S., and drug abuse is one of the main sources of crime and disorder, Adams is right to tackle this issue directly.

Even with civil commitment laws for substance abuse, most mandatory drug and alcohol treatment will come via the courts, since most criminals also abuse drugs and alcohol. The government estimates that two-thirds of those in prison have an ongoing addiction problem.

Other mandatory drug and alcohol treatment will come through the mental-health system. Many individuals with severe mental illnesses also have a co-occurring substance use disorder, and more than half of the severely mentally ill used illegal drugs over the previous year. Increasing civil commitment for mental illness, which Mayor Adams helped shepherd through the New York state legislature earlier this year, will thus help many of those with addictions.

Some people will still fall through the cracks without a civil-commitment law for substance abuse, however, especially those who threaten themselves more than others. Adams’s proposal thus points New York in the right direction, offering help to those who cannot help themselves.

Judge Glock is the Manhattan Institute’s director of research and a contributing editor of City Journal.

Photo by Lev Radin/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).