You’re standing in the wine aisle and Google a review for a bottle in your hand. Its description could be interchangeable for a perfume ad: “gorgeous boysenberry, stained finish, exotic spice.” You nod, pretending to understand a language made up of fruit and furniture. You take a sip, and it tastes good. But which words told you that ahead of time — gorgeous, stained or exotic?

If wine adjectives feel like riddles, you’re not alone. Whether you’re in the wine aisle or buying online, a few lyrical terms can tip a pricey decision. Wine reviews often read like insider dialect, decipherable to only the most seasoned of wine enthusiasts, said Jing Cao, a professor of statistics at Southern Methodist University and fellow of the American Association of Wine Economists.

That disconnect is why Cao turned to a technique called sentiment analysis — using AI to bring clarity to the tasting-note chaos for everyday wine drinkers. In a paper published in the Harvard Data Science Review, Cao and her colleagues at SMU built an AI model that highlights specific words in a review that carry the positive or negative sentiment, the ones doing the persuading.

Sifting through the emotions

Breaking News

As humans, we do sentiment analysis all the time: while reading a text or a social media post or during real-life conversations. We judge whether the language conveys an upbeat, flat or ominous interaction. That intuitive read is sentiment analysis in miniature, Cao said.

“Nowadays, we live in a material world that’s very buying and selling,” Cao said. “I don’t think you will blindly purchase something — you look at the rating, you look at other customers’ reviews or feedback.” This process of mining others’ opinions to make informed decisions is sentiment analysis, Cao added. “It’s not a manual on how to use [a product] or how to drink it and what it tastes like. It’s to see how enthusiastic people feel about it.”

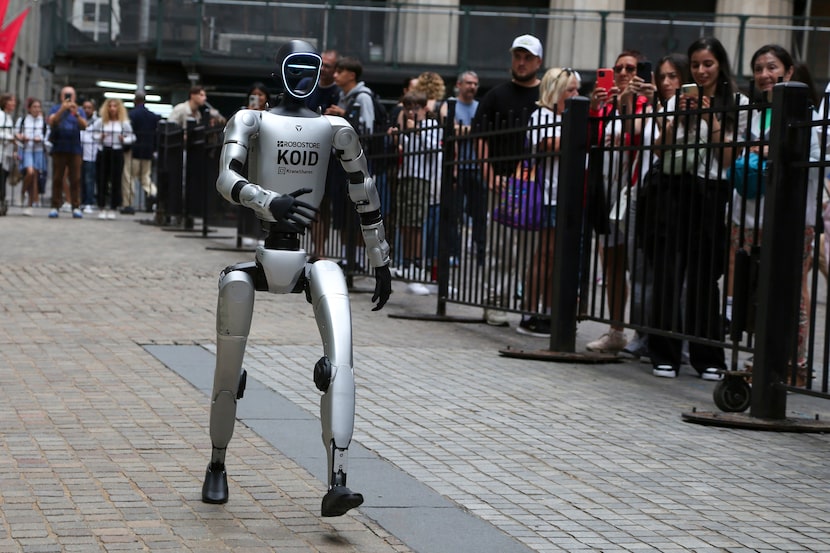

A Unitree G1 Edu humanoid robot capable of squatting, running, clapping, waving and lifting light objects greets visitors at the New York Stock Exchange in New York on Friday, August 1, 2025.

Ted Shaffrey / AP

But enthusiasm, and its absence, are felt keenly in the wine aisle. Reviews speak in vivid, bold descriptors about the aroma, body, flavor and finish that either beckon or warn off potential shoppers, said Carl Hudson, a certified wine specialist and educator with the Texas Wine Collective.

A 2017 study from the University of Adelaide in Australia found that evocative language not only influences which wine we buy but also shapes our emotions, nudging us to pay more for what we perceive as a more elaborate wine — and, in turn, to like the wine more when we finally sip it.

If words can steer wallets and palates, the obvious question is which words are doing the steering and how?

That question has long fascinated Cao, a self-described foodie interested in wine and consumer behavior. During the pandemic, with some grant funds left over, she and a few graduate students set out to answer that question.

A 2022 study published in the Journal of Wine Economics showed that AI can scan wine reviews from Wine Spectator, a well-known wine magazine, and reliably predict a critic’s score. Building on that idea, Cao and graduate student Chenyu Yang developed an AI system called an attention-based multiple instance model that analyzed over 140,000 Wine Spectator reviews written between 2005 and 2016.

If you imagine a wine review like a bag of grapes, the AI figures out which words are the grapes carrying the flavor, both individually and within a sentence.

Bottles of wine in a cooler at Neighborhood Cellar, a wine bar in Bishop Arts, on Thursday, Sept. 23, 2021, in Dallas.

Smiley N. Pool / Staff Photographer

Among the top positive sentiment words were ones anyone would expect: gorgeous, seductive, exquisite, velvet, sumptuous and impeccable. Others weren’t — breed, soak, carpet and fabric — but in wine-speak, they read as praise.

Some words the AI flagged as negative sound otherwise positive in everyday speech: Picnic, watermelon, decent or breezy. Hudson said such words aren’t desirable qualities, often signaling simplicity rather than depth. Picnic, for instance, suggests a white wine pleasant enough but short on elegance or character, he added.

Sentiment beyond wine

Compared with other sentiment-analysis models — like Google’s BERT, which was developed in 2018 and reads words in both directions to capture context — Cao and Yang’s model hit 89.26% accuracy on the two-class test, edging past BERT’s 89.12%.

Impressive as that is, especially against BERT, Cao said their AI isn’t ready for the linguistic wilds of X or other online forums. On social media, a single word can swing from praise to snark depending on context; wine reviews are far more uniform. However, Cao is hoping to do more research and work on the AI to get it there.

Despite gloomy surveys about the future of AI taking human jobs — and as its use creeps through the wine industry from farming sensors to virtual sommeliers — Hudson, a wine reviewer himself, welcomes the burgeoning technology.

“If people get something out of that, learn enough about wine to then accept the sentiment that AI gives them, or let the AI sentiment guide them to a particular type or set of wines,” Hudson said, “I think that’s very valuable for our wine business. If we can grow more grapes and make more wine, I’m all for that.”

Beyond wine, Cao sees her AI helping decode the sentiment in other jargon-heavy worlds. An example could include doctor-speak during an annual check-up: translating it clearly could close communication gaps that contribute to health disparities. The use of sentiment analysis in health care is being explored to some extent, such as using AI to sort whether patient reviews online of physicians skew positive or negative.

“Not only do I need to know what, but I would like to know how — why is this labeled in this way, why is this characterized in this way,” Cao said. “That’s the power of interpretable AI.”

Miriam Fauzia is a science reporting fellow at The Dallas Morning News. Her fellowship is supported by the University of Texas at Dallas. The News makes all editorial decisions.