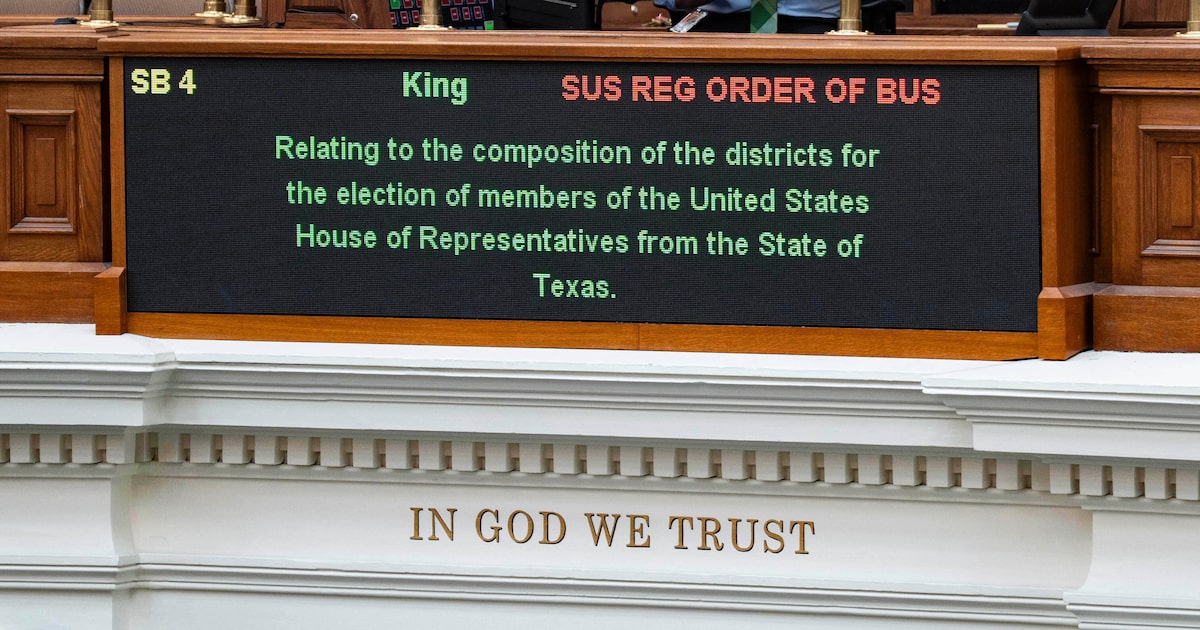

Under the new congressional district maps proposed by Texas House Republicans, I could get a new representative.

The 33rd Congressional District, currently represented by U.S. Rep. Marc Veasey, D-Fort Worth, covers the majority of West Dallas but would be divided from its Tarrant County portion, Veasey’s home base.

Neither Veasey nor U.S. Rep. Julie Johnson of Farmers Branch, two of the three Democrats who represent Dallas in Congress, live in their newly proposed congressional districts, though they technically don’t have to live within the district to run for the seat.

My community would be joined with comparable communities such as Pleasant Grove but mostly dissimilar mid-to-high income neighborhoods, including Oak Lawn, Uptown, Kessler Park, Little Forest Hills, Casa Linda and Buckner Terrace. It would also add economic engines such as the Dallas central business district, the Dallas Medical District and Love Field.

Opinion

What would be an economic gain for my congressional district would be a loss for the 30th Congressional District. The proposed maps would deliver dire economic effects there, remove economic engines that previously provided balance to the district and dilute the Black vote.

Judicial retreat

We’ve entered an era when politicians govern through legal processes as much as legislative proceedings. In recent years, there has been a notable increase in the number of court cases addressing legislative matters, particularly the power of states. The current Republican redistricting power grab wouldn’t have been possible without a few pivotal court decisions that weakened voting rights.

It’s important to note the comprehensive nature of the Voting Rights Act, which turned 60 years old this month. Though its provisions specifically address historical and systematic discrimination faced by racial and language minorities, its purpose was to protect the voting rights of all citizens. What we are seeing today is a judicial dismantling of voting rights.

In the 2013 case of Shelby County vs. Holder, the Supreme Court struck down Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act, which determined, through a specific formula, eligible jurisdictions considered to have a long-standing history of voter discrimination. These jurisdictions were subject to Section 5 of the act, which required preclearance from the attorney general or a federal court before implementing changes to election procedures. Ruling the formula in Section 4(b) unconstitutional freed those jurisdictions from federal oversight of voting laws including redistricting plans and maps.

Immediately after the ruling, Texas officials announced plans to implement a voter ID statute.

More recently, the 2019 Supreme Court case of Rucho vs. Common Cause relinquished federal oversight of partisan gerrymandering — the manipulative structuring of districts to favor one party.

Republicans and Democrats are guilty of this practice, though a recently published national scorecard by Princeton University revealed that out of the 15 states with the highest evidence of gerrymandering, 10 are red.

John Adams, our second president, said a democratically elected body “should be in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large.” Even if it emerges from partisan motives instead of racial ones, gerrymandering distorts that principle.

Racially packed

Even though racial gerrymandering is still prohibited under the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, under the Rucho decision there is little distinction between the intent of partisan gerrymandering and its racial effects. State legislators can pack a congressional district with one demographic and simply say it’s about politics, not race.

Under the proposed maps, the 30th Congressional District, currently represented by U.S. Rep. Jasmine Crockett, would become overwhelmingly Black. That’s a gerrymandering strategy called “packing.” It’s the redistricting equivalent to the age-old practice of redlining — cramming all the people of one race into an area excluded from opportunity.

The proposed map would be a legislative death sentence for southern Dallas. It would weaken the leverage that comes with a balanced district and group our poorest communities together. making it difficult to spur economic opportunity.

Much of the new district is in areas where poverty rates are greater than 20% and which house some of the lowest-income ZIP codes in the entire Dallas-Fort Worth area. A good portion of the district would be made up of three of the four Dallas City Council districts with the lowest property values in the city. If you combine the values in those three districts it would make up about 6% of total property value of all of Dallas.

Although the district will also include some middle-income neighborhoods like Kiestwood in Dallas, and pockets of high-income areas like DeSoto and Cedar Hill, these areas still struggle to find their economic footing due to being surrounded by strongholds of concentrated poverty. With the exclusion of previously included areas like downtown and the medical district, the 30th Congressional District and southern Dallas would be economically excluded from our city’s economic growth, and it certainly wouldn’t mirror what we know to be true about the Texas economy.

U.S. representatives have one primary job — leverage their positions to secure resources for their district. When Crockett co-led the efforts to land the coveted Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health’s regional headquarters at Pegasus Park in her district, it came with significant leverage that could be used to lift up weaker parts of southern Dallas.

The newly proposed 30th District map would deduct the much-needed balance and every bit of leverage that Crockett currently has when attempting to steer resources for her constituents.

Texas’ actions will have a ripple effect across the country. Democratic governors are preparing to counter Texas’ actions with partisan gerrymandering that will further weaken equal representation of voters and prioritize power over people’s economic futures. When the political tides turn, the proposed maps will be contested and will most likely change, creating an upheaval that vulnerable sectors like southern Dallas don’t need.

There are economic effects to political action, and in the case of current redistricting efforts, southern Dallas will once again get the short end of the stick.