Back in 2017, when I served as the president of the Dallas Park and Recreation Board, Dallas voters approved bond funds for the first time in more than half a century to build new public swimming pools.

Since then we have spent more than $75 million on new aquatic facilities throughout the city.

These modern aquatic centers were designed to serve the community for decades to come. Those projects were not simply ribbon-cutting opportunities; they were the product of over six years of careful study, public engagement, and a long-term strategy outlined in the city’s Aquatic Facilities Master Plan.

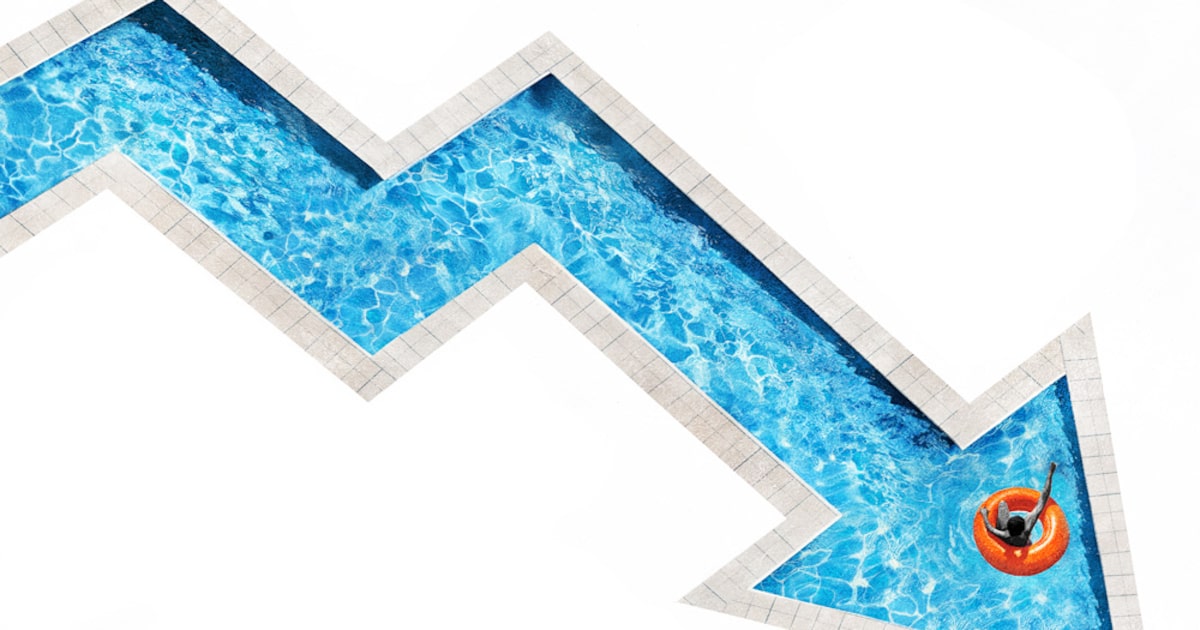

That plan was clear: Dallas could not afford to maintain our sprawling network of aging, underutilized and deteriorating neighborhood pools. Instead, we needed to invest in fewer, larger and better-equipped facilities that could serve more people, cost less per swimmer and offer a wider variety of activities.

Opinion

We’ve understood for a long time that the cost per user of our legacy pools is not sustainable. Fifteen years ago, this newspaper reported that taxpayers shelled out $136 for each swimmer at the Exline legacy pool in South Dallas, which was replaced with the Exline Neighborhood Aquatic Center in 2023.

The tradeoff was obvious even then as it is now. To build for the future, we would eventually have to close some of the past.

We have delayed the inevitable long enough and that time has now come.

Last week, City Manager Kimberly Bizor Tolbert and Park and Recreation Director John Jenkins made the tough but necessary call to recommend closing two of our oldest community pools. They deserve credit, not criticism, for following through on what decades of planning and data have told us: These pools are no longer serving the public interest.

The facts are straightforward. The city is facing a budget shortfall, and every department has been asked to stop doing things that no longer make sense. For Park and Recreation, that means looking at inefficient services. Aging pools top the list.

Our legacy neighborhood pools date as far back as 1947. They have far exceeded their life expectancy and would cost millions each to repair or replace. Meanwhile, the average daily attendance has dropped sharply, numbering in just the dozens for most.

It’s not hard to understand why closing public pools is such a hot-button issue when you look at our city’s past handling of the issue.

In their heyday, our legacy pools were neighborhood centers, even as they served as symbols of racial segregation. When, in the middle of the 20th century, Dallas began a project of building community pools, it had to face the question of access for Black residents.

In 2016, Dallas archivist John Slate and former Park and Recreation director Willis Winters chronicled the history of segregation in Dallas’ park system. Pools were a particularly fraught area for the legendary parks director L.B. Houston, who favored integration but recognized “that the very last thing that white people would tolerate would be mixed swimming,” Houston said.

Houston set up a grid system of “homogeneous communities and a swimming pool in the center of each. So as you trace those pools that were built they went into black and white communities,” he said, according to the history written by Slate and Winters.

Houston enjoyed the necessary political support of oilman Ray Hubbard, who was the Park Board president during much of Houston’s tenure and who had the standing to ensure that Black neighborhoods were not left out when it came to community pools.

That’s a big reason why, when it comes to cutting pools, the political question looms so large.

During my own time as park board president, this was the legacy we faced, even as we understood that many of the pools Houston and Hubbard had built no longer served their communities as they once did.

The goal was to preserve access to swimming facilities, but to ensure they were useful to all neighborhoods regardless of race or socio-economic status. Our job was to ensure that every Dallas resident, especially those without access to private pools, had an opportunity to swim. Especially in southern Dallas, where the rates of children with swimming proficiency were at an unacceptably low level, so much so that they faced a much higher risk of drowning than kids in northern Dallas.

The 2015 Aquatic Facilities Master Plan showed that traditional pools recovered less than 20% of their operating costs, compared to much higher recovery rates at regional aquatic centers. They also serve a smaller geographic area, often duplicating service in places where a modern aquatic center or YMCA is nearby.

In contrast, the new facilities such as Crawford, Fretz, Samuell Grand, Lake Highlands and, most recently, Bachman Lake are thriving. They offer lap lanes, lazy rivers, slides, splash areas, climbing walls, party rentals and concessions. They attract not just nearby residents but families from across the city, helping build community while also generating significantly more revenue per visit.

Closing some pools was always part of the plan. When our City Council-appointed Park Board members adopted the Aquatics Master Plan, they explicitly chose a hybrid model; three large regional family aquatic centers, five community family aquatic centers, and a small number of spray grounds to replace 20 aging traditional pools.

We did not have the funds to maintain both systems, nor would it be wise to do so. Each dollar spent keeping an obsolete pool limping along is a dollar not invested in safe, attractive and accessible aquatic recreation for the next generation.

Back then, we knew it would take political courage to follow through. Closing a facility, even one that is underused and falling apart, is never popular. But good leadership isn’t about popularity, it’s about making decisions in the long-term best interest of the city.

City Manager Tolbert and Director Jenkins are doing exactly that.

This is not about taking something away, it’s about aligning resources with impact. Critics may focus on the idea of “losing” pools, but the reality is that Dallas residents now have access to more aquatic amenities than at any point in our history. Since 2018, we’ve opened multiple new centers across the city, strategically located to provide equitable access. Many of the pools now under review for closure are within a short distance of a newer, larger facility.

The numbers speak for themselves. Legacy pools average just over 6,000 visits per year, while newer centers can serve that many people in a few weeks. Operating costs per swimmer are dramatically lower at the new facilities, and cost recovery is higher. That’s good stewardship and the very definition of good government.

Yes, some residents will miss their local pool. And, yes, transportation and access are valid concerns that must be addressed through shuttle programs, partnerships with schools, or expanded hours at nearby centers. But clinging to facilities that no longer meet today’s standards is not fairness. It is waste. Data, not nostalgia, should guide the decision.

In this case, we did our homework years ago. We built for the future, knowing some of the past would have to be retired. Now, the city is following through. We should applaud Jenkins and Tolbert for their willingness to make a politically sensitive but fiscally and operationally smart decision. They are honoring the intent of the Aquatics Master Plan, respecting taxpayer dollars, and prioritizing facilities that deliver the most benefit to the most people.

Robert Abtahi has served on boards for Dallas Park and Recreation, the Dallas Zoo, Friends of Fair Park and the State Fair of Texas.