PARIS — The bowl cut, the cats, the heart-shaped potatoes. The predilection for loopy plots and faces hidden in household objects. Whether posing with angel wings or swallowed by a giant Muppet-like coat, the late artist and filmmaker Agnès Varda (1928–2019) has long been a patron saint of the unabashedly eccentric. A master of self-invention, she crafted a persona as singular as those she shot for the screen.

Fittingly, Agnès Varda’s Paris, from here to there, at the Musée Carnavalet till August 24, plumbs Varda’s enduring fascination with performance. “I like that artists disguise, mask, and deform reality,” she is quoted on a gallery wall. Featuring 130 photographic prints, film excerpts, and an eclectic array of her personal effects in, the exhibition honors the artist’s waggish sensibility, my personal favorite being a photo of a human face found in a bath faucet. But more urgently, the show reveals how Varda’s creative vision not only “masked” the real world, but was inspired by her lived reality — as a Brussels-born bohemian building a career in the big city, a trailblazing New Wave auteur, a vocal radical feminist, and, perhaps most surprisingly, a queer artist whose interest in gender fluidity was reflected in her early photographic portraits.

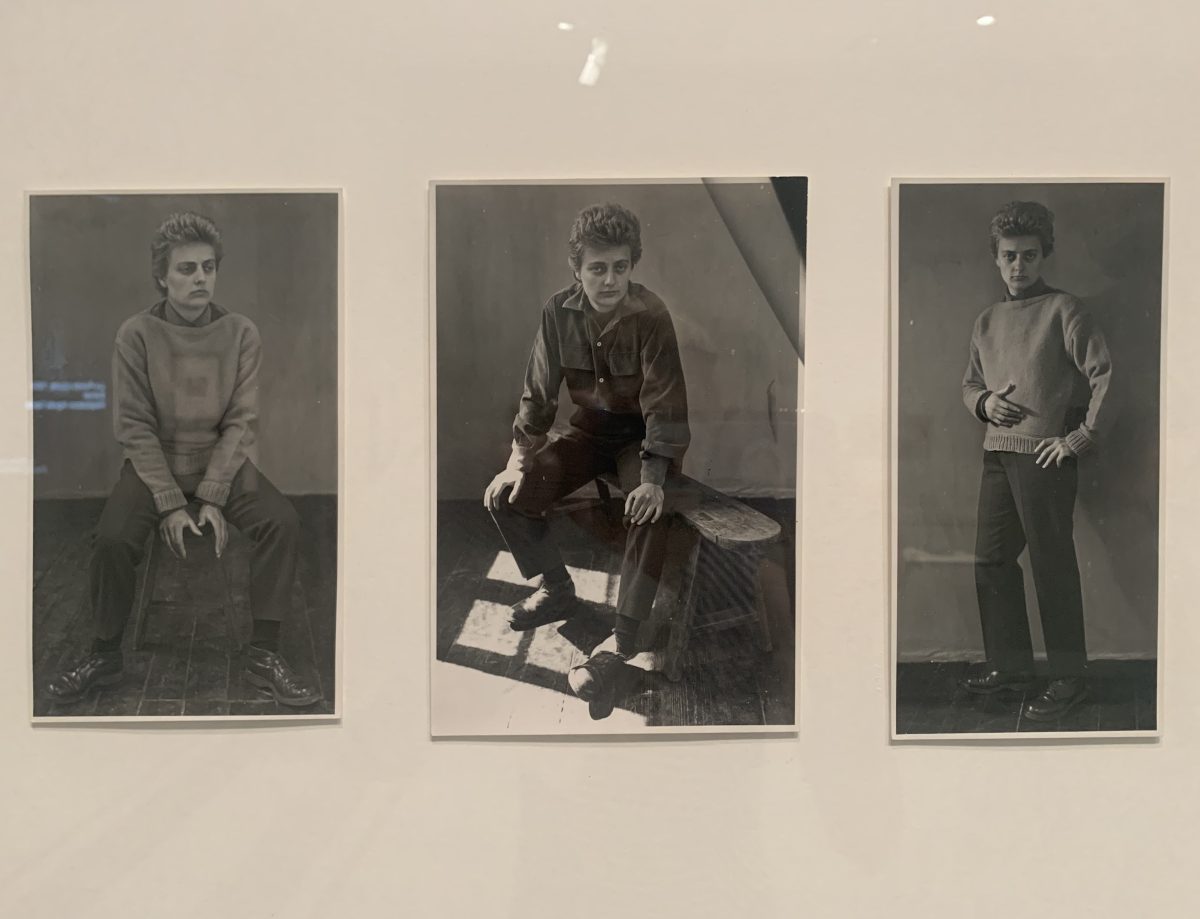

Varda’s photos of Valentine Schlegel in the studio in 1952, on view in from here to there (photo Eileen G’Sell/Hyperallergic)

Many devotees are familiar with Varda’s marriage to acclaimed filmmaker Jacques Demy, whose bisexuality was revealed after his death from AIDS-related complications in 1990. Fewer are aware that, years earlier, she shared a life, home, and creative practice with French sculptor and ceramist Valentine Schlegel. In 1951, three miles from the stately manses that abut the Carnavalet today, Varda and Schlegel moved into two neglected boutiques on 86 Rue Daguerre in Montparnasse. In line with the street’s namesake (photographer Louis Daguerre, inventor of the daguerreotype), Varda and Schlegel transformed one of the buildings into a photography laboratory, the other into a ceramics studio. At the home’s entrance, an orange plaque designed by Schlegel featured Varda in her signature coif.

1955 photo by Varda of a friend wearing angel wings, on view in from here to there (photo Eileen G’Sell/Hyperallergic)

In one of Varda’s earliest portraits on display in the exhibition, from 1947, Schlegel dons a drawn-on mustache in front of a painter’s canvas, drolly parroting the self-serious nature of the male modernist artist. In another taken a few years later, Schlegel and sister, the ceramist Frédérique Bourguet, pose in sober silhouette on the steps of Montmartre. In a 1954 series of Schlegel, she dons androgynous attire while straddling a stool and a bench. On the occasion of Schlegel’s 30th birthday in 1955, Varda captured a male friend posing shirtless in gilded angel wings, coyly smiling with his arms crossing his bare chest.

While the wall signage and object labels steer clear of didacticism, fans of Varda’s later work — her 1962 masterpiece Cléo from 5 to 7, her 1977 abortion-rights musical One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, or her collaborations with cinematic luminaries like Jane Birkin — might be delighted witness just how free-wheeling and queer the artist’s social circle was during the late ’40s and early ’50s, one of the most homophobic periods in French history. What from here to there implicitly celebrates is not only how Paris influenced a 20th-century icon of film, but how queer culture and merriment played a critical, if often overlooked, role in the artistic communities that brought the very concept of “Gay Paree” to life.

Agnès Varda’s Paris, from here to there continues at the Musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris (23 Rue de Sévigné, Paris, France) through August 24. The exhibition was curated by Valérie Guillaume, director of the Musée Carnavalet, and Anne de Mondenard, head curator of the Photographs and Digital Images Department of the Musée Carnavalet.