Wages have largely lagged behind inflation over the past few years, a shortfall attributed to a post-pandemic price surge the effects of which continue to reverberate through the economy.

According to a new study by financial services firm Bankrate, inflation has risen 22.7 percent while Americans’ wages have only grown 21.5 percent since January 2021. This has resulted in a current wage-to-inflation gap of -1.2 percent, meaning that income has on the whole failed to keep pace with overall price increases.

Why It Matters

The disparity between wages and inflation means most Americans—even those who have received bumps in their paychecks—are effectively seeing a drop in their in overall purchasing power. However, while some industries lag well behind, researchers found that certain professions have seen their pay keep up with, even outpace, price hikes since the pandemic.

What To Know

Bankrate drew on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics—specifically the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Employment Cost Index (ECI)—to measure sector-specific wage growth against inflation since 2021, and found that four industries have seen wages rise faster than prices over this period.

Earnings in the accommodations and food services category have risen the fastest since 2021, climbing 27.5 percent and exceeding inflation by 4.8 percent. Next is leisure and hospitality, where wage growth has created a 4.1 percent lead over inflation. Health care and social assistance follows with a 1.7 percent wage-to-inflation gap, while retail earnings have outpaced price increases by 0.5 percent.

Elise Gould, senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute and an expert in wage dynamics, told Newsweek that areas such as leisure and hospitality “experienced much faster wage growth coming out of the pandemic because of the sheer numbers of jobs lost and the need for employers to scramble to attract and retain workers.”

These effects, she said, were more pronounced for those at the lower end of wage distribution, who required more “enticement” from employers to return to less-compensated, face-to-face roles—bargaining power that was reinforced by the financial supports put in place by policymakers during the pandemic.

Ahu Yildirmaz, President & Chief Executive Officer of the nonprofit Coleridge Initiative, which assists governments in using data for policymaking, said that the sectors where wages have kept up “not only faced intense competition for workers, but they also started from relatively lower wage levels.”

“That means percentage increases appear larger and more noticeable,” he told Newsweek, adding that health care is a “bit of a special case,” given funding support during the pandemic “helped reinforce wage gains, adding to the upward pressure.”

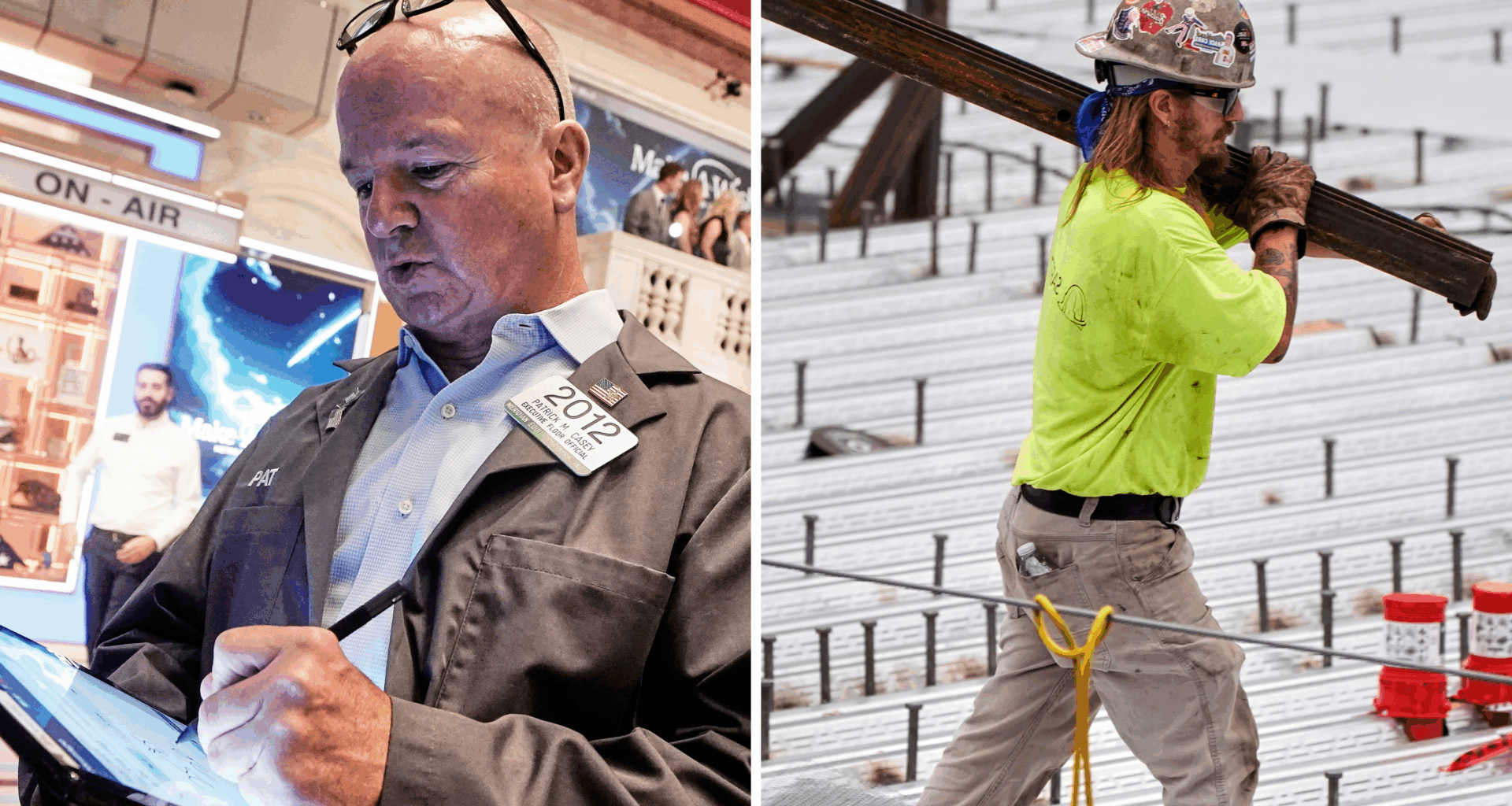

A trader works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Monday, August 18, 2025. A welder carries steel at the site of a construction of a housing project, Thursday, July 31, 2025, in…

A trader works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Monday, August 18, 2025. A welder carries steel at the site of a construction of a housing project, Thursday, July 31, 2025, in Portland, Maine.

More

Richard Drew / Robert F. Bukaty/AP Photo

In contrast, wages for those in manufacturing, professional and business services, financial activities and construction have slipped noticeably behind inflation. Education has fared the worst, with a 17.9 percent rise in pay trailing inflation by 4.8 percent.

Educators have long suffered from the gap between income growth and inflation. According to the National Education Association’s most recent annual report, average starting teacher salaries underwent their largest increase in 15 years in 2024. However, the labor union said that, when factoring in inflation, average teacher wages have “actually decreased by an estimated 5.1 percent over the past decade.”

“Education has lagged the most because even though teacher shortages persist, institutions face far more rigid pay structures,” Yildirmaz told Newsweek. “School systems can’t easily adjust prices or salaries in the way private employers can, so teacher pay scales tend to move slowly and remain constrained.”

Gould noted that the inability of wages to keep up has also been a function of the rapid inflation seen between 2020 and 2022, which reached an annualized rate of 9.1 percent in June 2022. This has been attributed to a mix of factors including pandemic-era supply chain shocks, post-lockdown demand surges, as well as the Russian invasion of Ukraine which drove up energy and food prices.

What People Are Saying

Martha Gimbel, executive director of the Yale Budget Lab, told Bankrate: “A wage increase is something you earn. Inflation is something that happens to you. It feels unfair to people that their hard-earned wage increase is getting eaten up by something that’s not their fault.”

Ahu Yildirmaz, President & Chief Executive Officer of the Coleridge Initiative, told Newsweek: “Looking ahead, demographics and immigration will play a critical role in shaping labor supply. At the same time, the pace of AI adoption will influence demand. In service industries where human interaction is harder to automate wage pressure is likely to remain elevated. By contrast, in sectors more exposed to automation, wage growth may be more restrained.”

What Happens Next?

Bankrate believes wage growth is on pace to match post-pandemic inflation by the third quarter of 2026, at which point its wage-to-inflation index will rise above zero.

According to latest CPI report from the BLS, inflation accelerated 0.2 percent in July from June, and is up 2.7 percent on a 12-month basis. The core CPI, which excludes the volatile food and energy categories, increased by 0.3 percent for the month and is up 3.1 percent from a year ago.

Most forecasts assume that inflation will remain broadly at this level for the remainder of 2025, the IMF forecasting annual inflation to hold steady at 3.0 percent on average this year. However, experts believe this will depend significantly on the extent to which the effects of President Donald Trump‘s tariffs are passed onto consumers.