Gislaine Williams grew up in Fort Bend County but the Honduran native didn’t become a U.S. citizen until she turned 18. She’s now a program officer for civic engagement at the Houston Endowment private foundation and gets to help others complete the process.

Houston Endowment announced earlier this month a $400,000 grant to the Houston Public Library system to expand its free citizenship classes. The grant covers a stipend for 15 instructors who teach courses at library branches throughout the city. Prior to the grant funding, just four instructors were teaching the high-demand classes.

About 360,000 people are living legally and permanently in Houston, most of them on a green card, but haven’t taken the steps to complete citizenship, Williams said.

“Naturalization is a priority area for us,” she said. “Everybody knows about the right to vote and freedom to travel, some of the key benefits of citizenship. The research also shows that citizens can earn higher wages, and they have higher rates of homeownership. We see it as a really big investment in our community.”

Citizens can also get a passport and become eligible for government benefits, added Gaspar Guevara, community involvement coordinator for Houston Public Library. And if an adult with dependent minors is granted citizenship, their children get it too.

So what’s stopping people from becoming American citizens?

Although the classes are free, the citizenship test application costs about $760. In addition to the cost of the test, people also balk at the time commitment, and some fear that they could draw negative attention from Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Guevara’s got answers to all those concerns.

Classes are offered at staggered times throughout the day and evening and at library branches in neighborhoods that have large populations of immigrants, he said. Those who take the courses get a waiver that covers half the application fee, and other financial assistance is available.

The two-hour classes are held once a week for six weeks, offered year-round with two-week breaks between each series. Participants can drop in, but registration is encouraged.

As for fear of being deported, that’s just not going to happen, Guevara said, adding that it’s imperative that city officials and nonprofit partners who offer the program, and those who have taken the classes, spread the word about what it is and what it isn’t.

Late last year, Guevara taught an English as a Second Language class with 27 students at a Houston public school. After President Donald Trump’s inauguration in January, only one participant showed up. He moved the class to a library and reached out to those who had stopped attending.

“We’ve had to change the narrative and spread the word that we are a safe environment,” he said. “There is a lot of misinformation out there.”

Instructors aim to keep the classes small so they can provide one-on-one instruction.

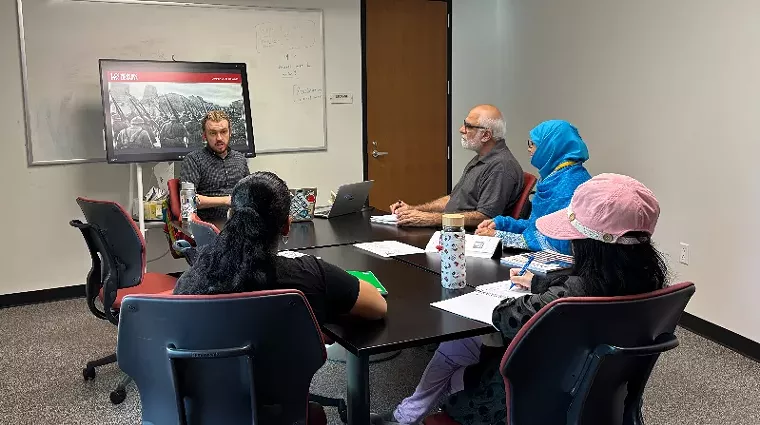

Photo by Houston Public Library

The citizenship classes are available to anyone, even if they haven’t been in the country for the required amount of time or have poor English speaking skills, Guevara said. The lessons cover reading and writing, civics, test preparation and mock naturalization interviews.

Fear of failing the citizenship test is one of the most common reasons for not starting the process, Williams said. About 40 percent of those eligible to naturalize in Houston have been in the United States for more than 20 years and don’t feel compelled to spend money on a test they might not pass.

“They’re part of our community and they’re American in every sense, but some people just don’t have the confidence level,” Williams said. “They’re really scared of the test. Something that Houston Public Library is able to do is build their confidence level and prepare them to go into the citizenship interview.”

The U.S. government and history test questions can be challenging even for native-born citizens, Williams said. The exam questions include, “How many members are in the House of Representatives?”, “Who wrote the Declaration of Independence?” and “Who did the United States fight in World War II?”

Guevara previously offered English and citizenship classes for the Harris County Public Library System and brought his expertise to the City of Houston in 2023. Since then, more than 1,200 people have taken the citizenship course, with enrollment tripling over the past year. Interest in the class has surged because people want protection from deportation, he said.

Guevara was born in the United States but his parents became naturalized citizens in 1984 and 1990. They didn’t have citizenship or English as a Second Language classes to help them through the process. Those who don’t pass a particular section of the test get a second chance to take it again, Guevara said, noting that his father had to take one section of the exam twice.

“That really lit the fire in me,” he said, explaining that his parents’ experience inspired him to make the process more accessible for others.

Williams said the Houston Public Library has taken a data-driven and thoughtful approach to the way it offers classes to make sure they’re accessible to the community, even referring participants to nonprofit legal resources if needed.

Williams was the first member of her family to take the citizenship test and said the process wasn’t comfortable, but she’s glad she did it.

“I’m a naturalized citizen, and even though I knew a lot of the information on the citizenship test, it was still such a nerve-wracking, intimidating process that I did all by myself,” she said. “I wish I had known about resources like the Houston Public Library classes because I know it would have gone a long way for me. It’s just important for people to know there’s support out there.”