This is part of “Cold-Blooded,” a series of stories by The Tributary’s senior investigative reporter Nichole Manna that unravels the 1993 prosecution of Kenneth Hartley, who is on Death Row. To read the whole series go to jaxtrib.org/cold-blooded

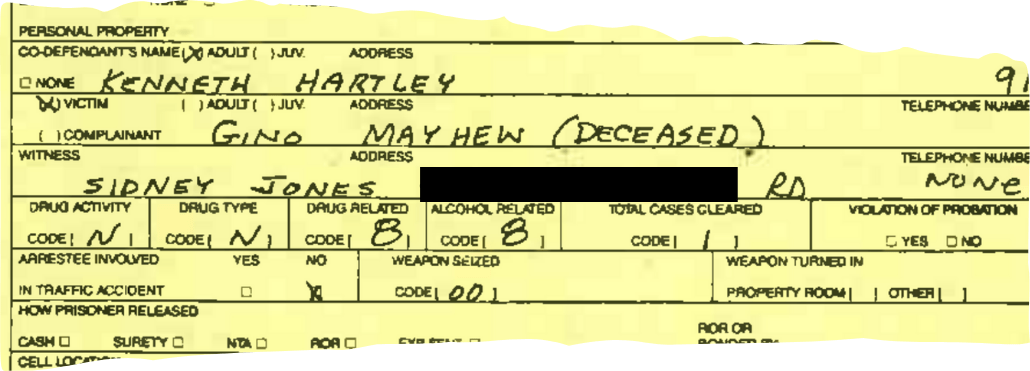

Sidney Jones is listed as a witness to Gino Mayhew’s kidnapping. [The Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office]

Sidney Jones is listed as a witness to Gino Mayhew’s kidnapping. [The Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office]

The day after Christmas 1984, Sidney Jones walked out of the Silver Star Lounge with a butcher knife in his back pocket, feeling bold. He spotted an approaching Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office cruiser and attempted to stash his knife under a car.

The deputies weren’t fooled. But even as he was collared and cuffed, Jones – who, as a felon, was barred from carrying a deadly concealed weapon – was defiant. He bragged that he’d wriggle out of trouble because he was an informant for a JSO detective who always took care of him.

True to his boast, he served no time for the charge.

Nine years later, a less-braggadocious Jones found himself in court, the key witness against Kenneth Hartley, a defendant on trial for his life in the kidnapping and murder of 17-year-old drug dealer Gino Mayhew. Jones was in the throes of a one-man crime spree, having been arrested 16 times over the previous two years while awaiting his day on the witness stand. For the record, Assistant State Attorney George Bateh asked Jones to tell the jury if his testimony was part of a quid pro quo to make the consequences for his law-breaking go away. Jones seemed taken aback.

“No, sir, state attorney … I didn’t ask for no help whatsoever.”

Jones’s testimony in 1993 was the key to putting Hartley on Death Row, where he remains today.

A growing pile of evidence, dug up in recent months by Hartley’s lawyers and The Tributary, suggests that Jones – whose adult life has been a 50-year bender of law-breaking and deceit – was less worthy of belief than was portrayed to the Hartley jury, calling into question whether anyone should face the ultimate penalty of death by execution based primarily on his word.

The Mayhew murder is not the only case in which Bateh is accused of using questionable witnesses to put a man on Death Row. At a hearing earlier this week in front of Circuit Judge Jeb Branham, lawyers for 54-year-old Michael Bell presented affidavits from two witnesses who said they were coerced either by Bateh or lead police detective William Bolena into falsely implicating Bell at his 1995 murder trial. After they were told they could face perjury charges for changing their original testimony, the witnesses refused to repeat their recantations in court. Bell’s execution remains scheduled for July 15.

Bolena was also the lead detective in the murder of Hartley, an investigation that was floundering until the detective produced Sidney Jones as a prime witness.

A cache of records recently obtained by The Tributary paints a vivid portrait of Jones, who was at once a petty thief, burglar, gunman, and liar, as well as a longtime paid police informant whose controlled buys gave cops probable cause for arrests. That relationship, which spanned decades, was not disclosed by the prosecution to the jurors who heard Hartley’s case, nor was the full scope of Jones’s rap sheet. He had nearly 40 convictions before Hartley’s trial began – remarkable in part because Jones’s misdeeds seldom landed him behind prison bars during decades when Florida prosecutors usually treated repeat offenders unsparingly.

Jones’s conviction and prison sentence for perjuring himself during a previous murder trial – a conviction later overturned on a technicality – went unmentioned at Hartley’s trial. The fact that Jones had been “blackballed” – jettisoned by JSO detectives as an unreliable informant – also didn’t surface. Bateh, a veteran Duval County prosecutor, presented Jones as a flawed man but credible star witness in the high-profile prosecution against Hartley and his two co-defendants. Whether Bateh was aware of JSO’s apparent loss of faith in Jones remains one of several open questions in Hartley’s case. Through an intermediary, Bateh declined comment on this story.

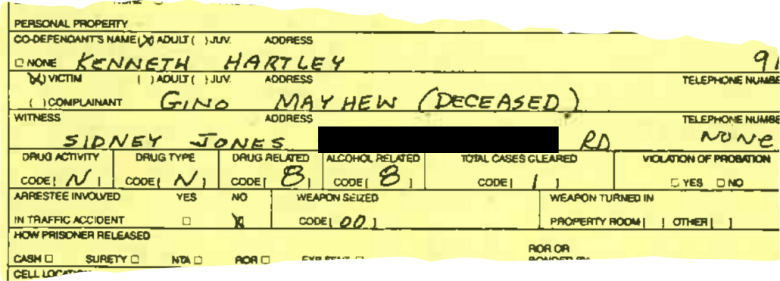

The 1979 arrest report accusing Sidney Jones of perjury. [Office of the State Attorney for the Fourth Judicial Circuit]

The 1979 arrest report accusing Sidney Jones of perjury. [Office of the State Attorney for the Fourth Judicial Circuit]

The Tributary’s reporting casts a harsh light on the decisions made by Bateh to portray Jones to jurors as a courageous and selfless neighborhood truth teller, while suppressing the stories of three other witnesses without Jones’s baggage. Their stories did not align as closely with the prosecution’s case.

Jones’s true motivation for testifying, which he revealed in a recent interview with investigators, was that he thought he would get paid for his testimony.

At trial, Bateh seemed to shrug off Jones’s record of law-breaking.

“Crimes conceived in hell do not have angels as witnesses,” he told jurors.

Richard Zitrin, an emeritus lecturer at UC Law and former criminal law specialist in California, disagreed that Jones’s background was of little consequence. “Most prosecutors I know wouldn’t even prosecute if somebody with that many felony convictions, including perjury, was the only witness.”

When The Tributary attempted to talk to Jones in December, he told a reporter he was too busy to chat and hung up. That number, and two others listed as his, have been disconnected. That same month, two journalists with The Tributary talked to Jones’s brother, who has since died. He said he didn’t know where Jones was these days. Told that the journalists were interested in speaking with Jones about his past testimony in a trial, his brother said, “He see everything.”

John Delaney, a former Jacksonville mayor and prosecutor who is close friends with Bateh, was highly critical of The Tributary’s characterization of Bateh in its original investigation. He defended the use of jailhouse snitches as a “very common” practice.

“It is human nature to talk and in fact to confess,” he wrote.

Others who study criminal justice found that frequency disturbing. A report by The Innocence Project found 367 exonerations that stemmed from the science of DNA and found that in nearly one of every five cases, a jailhouse informant had claimed the ultimately exonerated defendant had confessed.

Hartley’s lawyers are waging an ongoing fight for access to long-buried documents, especially related to Jones, who was a singular figure upon whom the bulk of the prosecution’s case relied. They are asking a judge to schedule an evidentiary hearing in hopes of getting a new trial or at least having the death penalty reduced.

What has emerged so far is striking.

The perjury episode from 1979 illustrated Jones’s willingness to bear false witness under oath, spinning up an elaborate fantasy. In the trial of two men charged with murder, Jones testified for the defense. He said he was at the Trailways Bus Station in Jacksonville and observed the two suspects pass through on the way to a liquor store. He testified he observed the arrests of the two men.

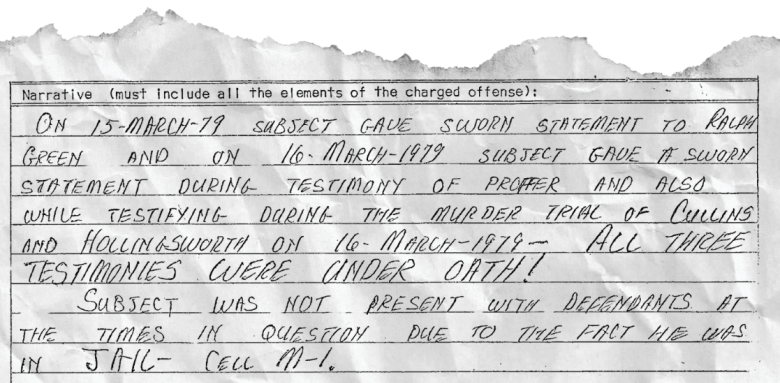

John Zipperer emailed Ronnie Ferrell’s appellate attorney in 2008, calling eyewitness Sidney Jones a “lying piece of shit.” It wasn’t until then that Ferrell’s team learned of Jones’s 1979 perjury conviction. [Office of the State Attorney for the Fourth Judicial Circuit]

John Zipperer emailed Ronnie Ferrell’s appellate attorney in 2008, calling eyewitness Sidney Jones a “lying piece of shit.” It wasn’t until then that Ferrell’s team learned of Jones’s 1979 perjury conviction. [Office of the State Attorney for the Fourth Judicial Circuit]

It was discovered during a recess that Jones was in jail at the time of those events and could not have seen anything of the sort. Afterward, Jones sought to return to the stand to correct his testimony, hoping to head off a formal perjury charge, but the judge said no, he was moving on, which is why the Florida Supreme Court eventually overturned the conviction.

Then there is the sheer volume of Jones’s rap sheet, recently obtained by The Tributary. The police reports sprawl across 150 pages, showing the witness to be a chronic criminal, spanning half a century.

In addition to charges ranging from theft to burglary to battery to drug dealing to contempt of court, the documents show him to be a gunman in his own right who shot a man in the arm after the victim purportedly handed over a firearm belonging to Jones to police.

Separate from Jones’s credibility issues, doubts have been raised about three jailhouse informants who testified that Hartley confessed to them behind bars. Several of their former cellmates now say the informants concocted their stories using information fed to them by a JSO detective. Hartley’s lawyers say two of the three informants have recanted, although one informant has since died.

A tale of abduction

The Washington Heights apartment complex (since renamed Calloway Cove) on Moncrief Road was a cluster of apartments plagued at the time –1991 – by drugs.

Gino Mayhew, a student at Paxton High School, didn’t live there, but sold drugs out of a friend’s apartment, according to court records. At night, the complex was a bazaar of competing dealers. Jones, who had been arrested for trespassing at the complex a week earlier, testified that on the night of Mayhew’s death, he worked for the teen by redirecting buyers away from other dealers and in the direction of Mayhew, whom he said had bigger, better rocks.

Jones told jurors that at around 11 p.m., he saw a suspicious huddle that involved Sylvester Johnson, Ronnie Ferrell, and Hartley, after which Hartley approached Mayhew’s Blazer, a gun in his bare right hand. He pointed it at Mayhew’s head. According to Jones, Hartley and Ferrell got in the SUV and the vehicle sped away, with Johnson following in a purple truck. Mayhew was found murdered the next day behind a school.

Rather than beep his JSO handler, Jones testified he went home, made a sausage sandwich, and smoked crack. He only got around to calling JSO to report what he’d seen two weeks later, after a new arrest for trespassing. He would testify against each of the three at their separate murder trials, and each was convicted. Ferrell and Johnson are serving life. Only Hartley is on Death Row.

In building his case around a man with a history of lying under oath, Bateh omitted testimony from at least three other people whose stories in some ways contradicted Jones’s. One was Gordon Shavers, who told police that the purple getaway vehicle Jones said was used during the kidnapping and murder never left the house where it was parked.

Then there was Kimberly Harris, Mayhew’s girlfriend, whose timeline of when she last spoke with Mayhew contradicted the timeline Jones gave police of when they were selling drugs and when the kidnapping occurred.

And, finally, there was Sharmeka Eunice, whom a detective testified he spoke to. He said she picked Hartley’s photo out of a lineup as the kidnapper, but she was not produced at trial. The lead investigator said she had moved to Atlanta.

Thirty years later, investigators working for Hartley’s appellate attorneys found Eunice, who told them she never picked Hartley out of a photo lineup and, contrary to what investigators stated, did not witness the kidnapping. Also, she said she had never moved to Atlanta.

Bateh, addressing the jury about Jones’s importance, hailed his bravery and declared: “Until Sidney Jones came forward, this was an unsolved murder in Jacksonville.”

But nothing in Bateh’s notes, or the notes from the now-deceased lead police detective on the case, indicate why they found Jones more credible – or courageous – than the other witnesses, who had no record of lying on the witness stand.

A lifetime of lawbreaking

The record shows that Sidney Jones’s very livelihood has been based on his ability to deceive.

When he was asked by defense attorney Robert Willis what he did for a living, he replied: “I don’t do anything.”

In fact, the cops regularly paid him, according to copies of JSO vouchers, to inform on fellow criminals, convincing them he was their ally while collecting evidence against them and then turning that over to law enforcement.

“He was literally financially backed by the police department,” said Rick Sichta, an appellate attorney who helped Ferrell get his original penalty, a death sentence, reduced to life.

In a pretrial deposition, Jones had said that while partnering with Hartley’s drug operation, he was also investigating Hartley with the intent of “[putting] him in jail.” But under questioning by Willis in front of the jury, Jones denied that.

Introducing Jones to the jury, Bateh said he had six felonies and a couple of marijuana arrests, understating the breadth of his record. He asked Jones if he had received any sort of a deal on the trespass charge he got just before he became the state’s prime witness. Jones replied he had not: “I served my 10 days on this case.”

Willis probed deeper, asking Jones whether he had caught a break from prosecutors on an armed robbery case, one of the 16 arrests, including five felonies, he had racked up in the two-year period while awaiting his time on the witness stand.

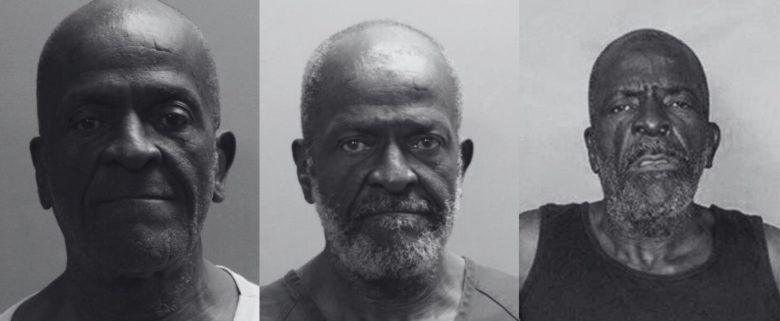

Sidney Jones over the years [Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office and Florida Department of Corrections]

Sidney Jones over the years [Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office and Florida Department of Corrections]

In that case, Jones was accused of robbing a Winn-Dixie of three cartons of cigarettes by indicating he had a weapon in his waistband. The prosecutor (not Bateh) initially moved to charge Jones as a habitual offender, which could have meant decades in prison. But the designation was dropped, citing — incorrectly — that he had too few felonies to qualify.

That robbery charge was reduced to attempted robbery, and Jones was sentenced to nine months in the county jail by Judge R. Hudson Olliff, the now-deceased jurist who was presiding over Hartley’s murder trial and who would eventually sentence Hartley to death.

Beyond the trial

The Hartley trial was a turning point in Jones’s life, he testified. He attested that he had sworn off smoking crack, although there would be at least one subsequent arrest.

More ominously, he was no longer a police informant shielded from the consequences of his crimes. That left him vulnerable when he was charged in 1994 with using a box cutter to rob an ADT employee.

The best he could do was negotiate two potential life sentences down to 15 years, 10 of which he served. Before officially sentencing Jones, Judge Alban Brooke rattled off Jones’s expansive record, which at that point included 20 arrests since Hartley’s 1993 murder trial.

“I would note for the record that you’ve been convicted on nine separate occasions of felonies,” Brooke said, according to a court transcript obtained by The Tributary.

Jones, who apparently had lost track, did a double-take.

“I haven’t had but three,” he argued. “Here, not too long ago, I was in a jury trial on three murder suspects, and the State Attorney, George Bateh, told me I only had three,” he added, misstating what Bateh actually had said in the courtroom.

During his stint in the prison system, Jones reached out to prosecutor Bateh several times and received phone calls in return, according to documents obtained by appellate attorneys working for Hartley. They are seeking additional records, trying to determine if Jones wanted or expected anything from Bateh other than assurances that he would not be housed in the same prison with Johnson, Ferrell, or Hartley.

By the time he was a free man in 2004, Jones’s zeal for illegal activity seemingly had dimmed. Arrests have been sporadic for the now 68-year-old.

It is a marked departure from his past, when even being behind bars did not impede his getting arrested – as was the case when he was charged with battery for slugging a fellow detainee in the Jacksonville jail.

According to the police report, Jones explained his actions thus: The man was a “snitch.”

This story was reported, written and edited by The Tributary, a non-profit investigative newsroom covering Florida. Senior Investigative Reporter Nichole Manna reviewed more than 65,000 pages of court documents – including court transcripts spanning 30 years and copies of prosecutor and detective notes – that she obtained through multiple record requests. Manna spoke to everyone involved in the case who is alive and was willing.

To read its other parts, go to jaxtrib.org/cold-blooded.

Related