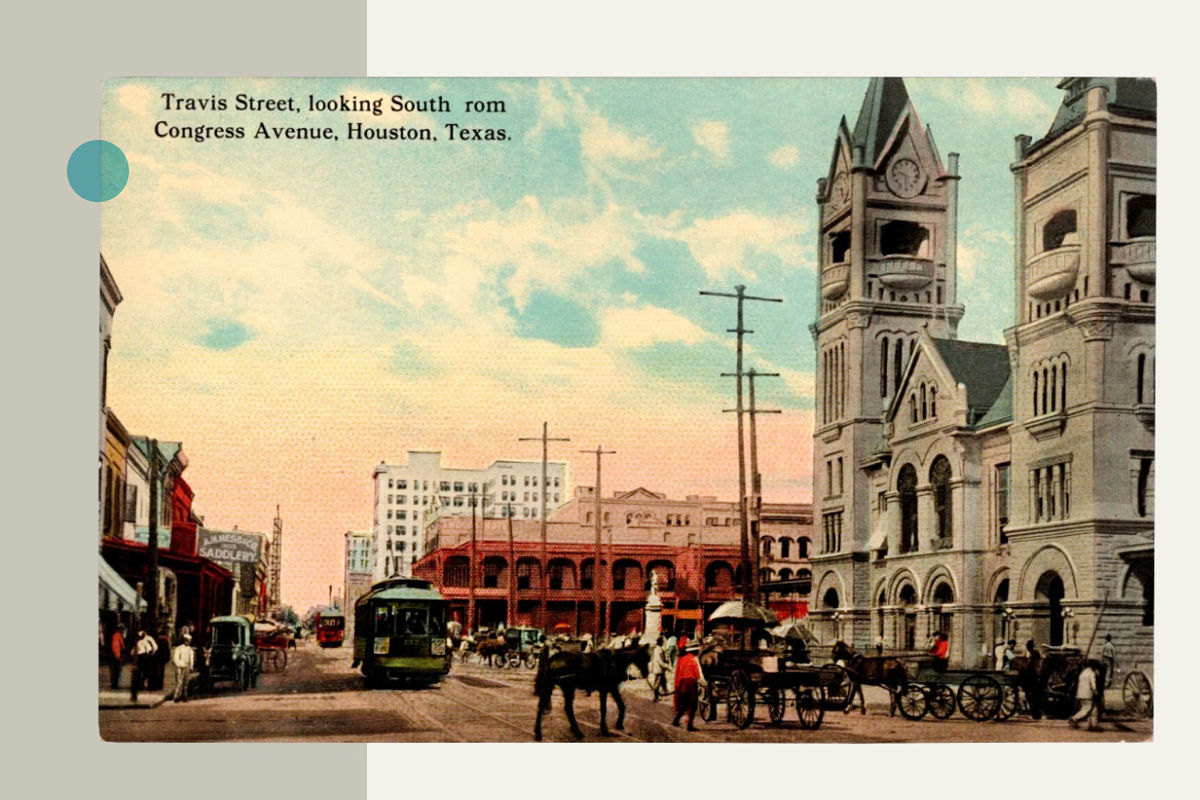

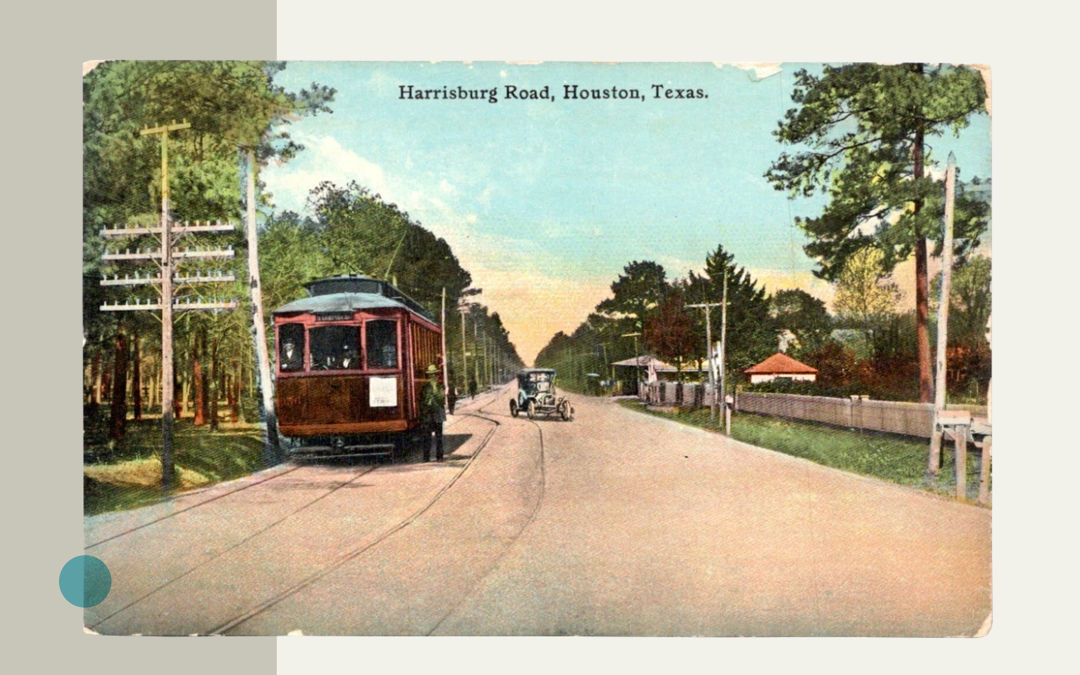

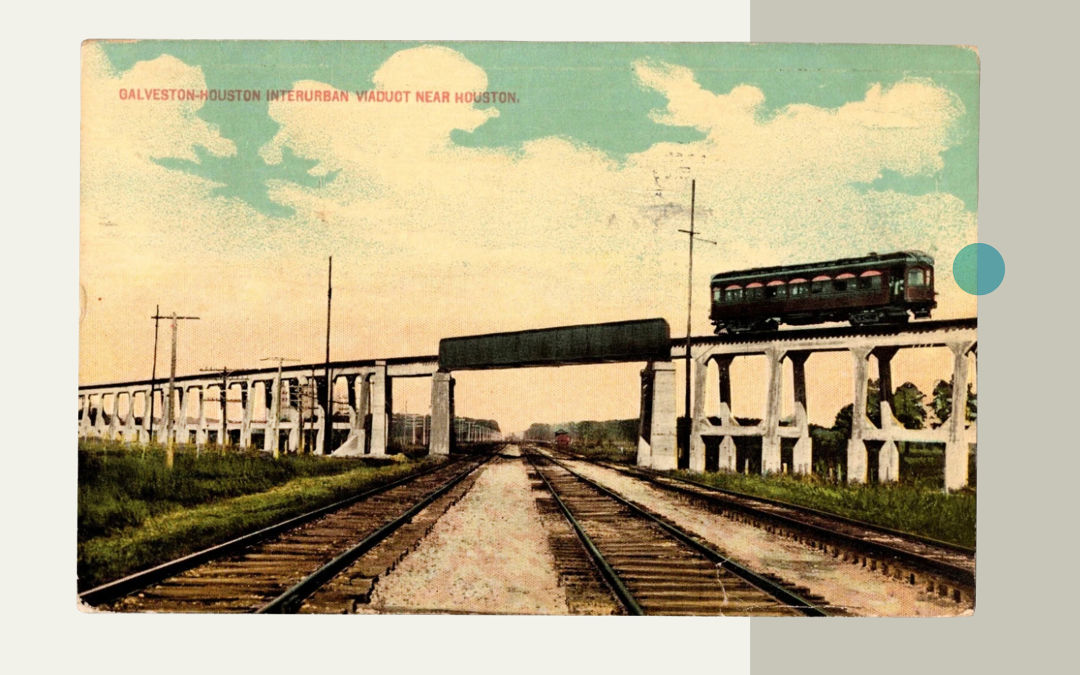

Early images of Houston’s mass transit are memorialized in postcards.

Cotton, oil, NASA, and the Texas Medical Center made Houston the city of the twentieth century, but it didn’t earn that title right away. For years, business leaders and politicians fought to turn Houston into a hub for commercial rail. Vast, interconnected train tracks and railroads connected to the Ship Channel, forging an alliance that allowed the Bayou City to emerge as a major American metropolis, where “seventeen railroads meet the sea.”

And the railroads weren’t the only method of transportation shaping Houston. From the first mule-drawn trolleys to electric streetcars, replaced by city buses, and finally light-rail, this city where it feels like everyone has their own car (or two) has sustained a commitment, albeit occasionally grudgingly, to mass transit.

In the years following the Civil War, Houston’s city limits were roughly what we now consider the contemporary boundaries of downtown. No suburbs yet, just muddy roads leading out of town to San Felipe de Austin, Washington-on-the-Brazos, Harrisburg, and Wallisville. Mud, in fact, was so prevalent that any and all alternatives to trudging through it were considered. In an era before poured concrete, road building might include shells, rocks, macadam (a composite with a binding agent), and even wood planks, with the best solution found in bricks. When competing trolley companies sought permission to install tracks for their commercial mule-drawn trolleys, steel tracks allowed for the most flexibility on the variety of Houston’s makeshift streets.

Houston’s original beating heart was downtown, where the streetcar system was one of the city’s original forms of transportation.

Seeing late-nineteenth-century Houston as a viable commercial center, banker Oscar M. Carter bought two existing mule car rail lines and merged them into the Houston City Street Railway Company. After getting the franchise rights from City Council, Carter built an electric trolley network on downtown’s still-muddy streets. In 1891, Houston’s first electric streetcars debuted. Carter later founded the Houston Heights and made sure his trolley lines ran there, too.

In 1908, William Wright Baldwin’s South End Land Company, developer of the subdivision Westmoreland, bought 9,000 acres southwest of Houston’s city limits for a new community dubbed Westmoreland Farms. Within this site, the town of residences and small farms was laid out, but the new development was so far away from Houston’s city limits that Baldwin knew access would be an issue. For the community, he built Bellaire Boulevard and an electric streetcar line to connect to Main Street. Dubbed the “Toonerville Trolley,” this line ran from 1912 until 1927. Today, you can see a retired trolley car sitting forlornly on the Bellaire Boulevard esplanade at South Rice Avenue.

Streetcars were among the earlier forms of urban transportation in Houston.

The reliable public transportation was key to the success of the Heights and Bellaire, two of the old city’s so-called “streetcar suburbs.” Today, a signature feature of the Heights is the landscaped esplanade running north–south from I-10 to 20th Street. This ersatz park was flanked by streetcar tracks that connected the community to Houston. (I would love to see a trolley line in the esplanade today, just like New Orleans’s streetcars on St. Charles Avenue. If Galveston can do it, then why not Houston?)

For a few decades, Montrose had streetcar lines, the most popular running along Mandell Street before returning downtown. The Fourth Ward’s Freedmen’s Town had its own trolley dating as far back as 1868. Remnants of steel tracks on a few hand-laid brick streets still hide in some of the Fourth Ward’s asphalt patches. Along the San Felipe line, the former residence of famed minister Jack Yates had become such a landmark that visitors were advised to “Ride the San Felipe Car and ask the conductor to let you get off at Jack Yates.’”

Perhaps the most ambitious transit project Houston has seen was the Galveston–Houston Electric Railway, dubbed the Interurban. Imagine hopping on a trolley (not a train car) in downtown and an hour later exiting on the Seawall! The 50 miles of dedicated tracks were occasionally elevated to cross over railways and existing roads. This simple line ran from 1911 until 1936, when automobile dominance made it obsolete.

Trolleys were all the rage in Houston’s streets.

In the early years of World War II, gasoline-powered buses completely replaced streetcars in Houston. Steel tracks were salvaged to be reused for wartime materials. Houston Electric Co., which had for decades run Houston’s streetcar network, transitioned fully to bus service provider. Over the next decades, other bus companies competed to serve the growing community.

Following a national trend, in 1974 the City of Houston bought the former Houston Electric Co., which at the time was owned by National City Lines, and renamed it HouTran. In 1978, voters approved the creation of the Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County (popularly known as Metro), which would be funded with a 1 percent sales tax increase. Metro took over bus service from HouTran and would commence management of the 400-bus fleet the next year.

Trains from Galveston to Houston were a major part of our transportation history.

Another transit development of that era: Houston’s subway, if it’s fair to call the subterranean people mover at Bush Intercontinental Airport a subway. Designed by the “imagineers” at Disney, the slow-moving, driverless cars have carried passengers between terminals for over 50 years, and still exude a low-tech, ’70s futuristic charm.

Jumping ahead to this century, MetroRail began service on January 1, 2004, marking the first time since Houston’s last streetcar ran in 1940 that car-loving Houstonians could use rail within the city. The 7.5-mile Main Street Line (later renamed the Red Line), a $324 million light-rail system, rolled on its maiden voyage with Mayor Lee Brown at the controls. The line connects Downtown, Midtown, the Museum District, the Texas Medical Center, and NRG Stadium, which would host Houston’s second Super Bowl just a month later.

In 2013, service was expanded to 13 miles, offering rail service to the Northline Transit Center. Today, MetroRail has three lines and covers over 23 miles. Metro is promising more tracks, and service to Hobby Airport, too. And yes, the trains’ booming, electronic clang-clang is an audio throwback to the city’s first streetcars over 100 years ago.