Corazón San Antonio hands out roughly half a million clean needles in exchange for used ones in a typical year, plus Narcan for drug overdoses, condoms and other items to prevent the spread of disease.

Corazón runs the only permissible and organized needle exchange program in Texas, made possible by a legal carve out that allows the practice in Bexar County alone.

There are other groups that operate in Texas, but they do so illegally.

The philosophy behind needle exchange is known as harm reduction, strategies aimed at reducing the negative health consequences associated with drug use and sex, but not requiring abstinence.

President Donald Trump issued an executive order in late July targeting this practice, instructing his administration to redirect federal funds away from organizations that operate under harm reduction and “knowingly distribute drug paraphernalia.”

If the Trump administration follows through, about $1 million in funding is at risk in Corazón’s $3.7 million budget. If the nonprofit can’t make up the gap through other funding streams, “we would not be able to save the lives that we’re saving today,” said Erika Borrego, Corazón’s president and CEO.

Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

CEO Erika Borrego and staff assist clients at Corazón Ministries at Grace Lutheran Church on Wednesday. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

CEO Erika Borrego and staff assist clients at Corazón Ministries at Grace Lutheran Church on Wednesday. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

President Trump’s July 24 executive order seeks to bring federal funding for homelessness programs in line with the administration’s strategy on homelessness. That includes shifting federal dollars away from organizations that prioritize housing assistance (known as “housing first” models) over addiction and mental health services, which the administration sees as the root cause of homelessness.

The order also favors “shifting homeless individuals into long-term institutional settings” through civil commitment as a core strategy of getting people off the streets, and encouraging cities to crack down on open drug use and enforce urban camping laws.

The order also labels harm reduction practices as ineffective “efforts that only facilitate drug use and its attendant harm.” Opponents of harm reduction principles argue that the practice only enable drug users, giving the impression that drug use can be done safely, and potentially attracting people to use who otherwise wouldn’t have.

According to Borrego and other supporters of the practice, harm reduction prevents the spread of diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C. It also offers crucial roads to addiction recovery and stability for the city’s homeless population, Borrego said, as well as people who have housing but are struggling with addiction.

“It’s a tool that allows us to build trust with our clients, and it gives them a reason to come to us,” Borrego said. “Once they’re comfortable, they’re more likely to ask for help. And when they ask for help, then the journey becomes finding them the right place to get to. Is it detox, is it a mental health bed, is it a place like Haven for Hope?”

Some research supports those claims. A 2013 meta analysis published in the International Journal of Epidemiology found that needle exchange programs and harm reduction practices help reduce the transmission of HIV.

A 2000 study published in the Journal of Substance Abuse and Addiction Treatment found that injection drug users in Seattle who participated in needle exchange programs were five times more likely to enter treatment for their addiction than those who didn’t.

Efforts to legalize needle exchange programs in Texas have fallen flat for two decades, despite often having bipartisan support. Former state Sen. Bob Deuell, a conservative Republican and physician from Northeast Texas, has argued that the programs make economic sense, given the high costs of treating blood borne diseases.

Texas had nearly 5,000 new HIV diagnoses in 2022, the highest of any state, and the fifth-highest rate of new diagnoses per 100,000 people the same year, according to KFF, a nonprofit health policy research, polling, and news organization.

Deuell was co-sponser of the 2007 bill that made way for Bexar County to run a pilot needle exchange program. A lack of support from local district attorneys, however, prevented any programs from officially getting off the ground in San Antonio for over a decade.

In 2021, Corazón — which also operates a day center for the city’s homeless —launched their needle exchange program at Grace Lutheran Church. According to Borrego, the nonprofit saved 1,500 lives with Narcan in 2024. Narcan is the brand name for the rapid-acting medication naloxone that reverses opioid overdose.

On average, the organization exchanges up to 600,000 used needles for clean ones annually.

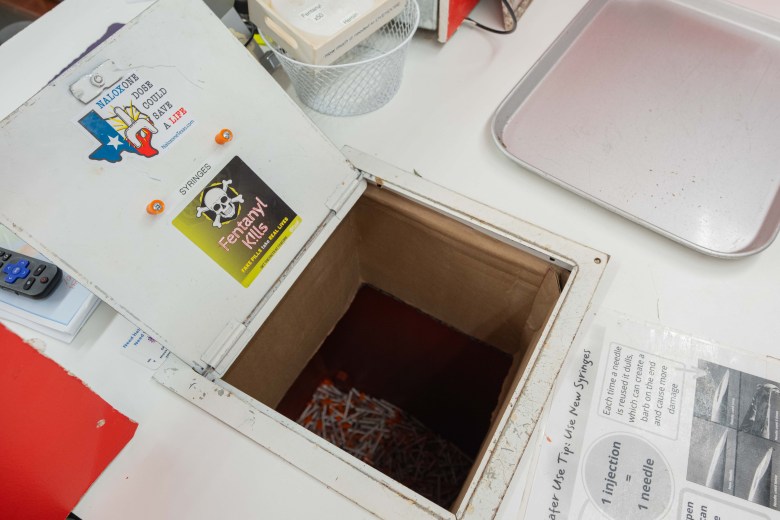

Clients are able to drop off and exchange up to 30 needles a day at the Corazon Ministries harm reduction center inside Grace Lutheran Church in downtown San Antonio. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

Clients are able to drop off and exchange up to 30 needles a day at the Corazon Ministries harm reduction center inside Grace Lutheran Church in downtown San Antonio. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

Although a few small grassroots organizations in San Antonio hand out clean syringes, Corazón is home to the only organized program consistently offering such services, Borrego said.

The nonprofit receives roughly $1 million in pass-through funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. That money is used not only for the needle exchange program, which costs about half a million to run, but a variety of other health and substance abuse related services.

The plan now is to wait and see. Even if the funding is cut, Borrego is confident that they could find other sources of funding to continue that work.

“Some of our folks have no one, and then we become their family that supports them,” Borrego said. “And that’s what we’re trying to do, is build community, build trust, to ultimately get people off substances, to get people off the street and in housing. And so where somebody might look at it as enabling, we look at it as life changing and life saving.”