1. The appropriations process will soon set budgets for the NIH and other federal agencies.

Congress must finalize federal funding — including for NIH, NSF, and CDC — by Sept. 30 through an appropriations process.

For the 2026 fiscal year, the Trump administration proposed slashing the CDC’s budget by half to $4 billion and NIH’s budget by 40 percent to $18 billion. However, senators from both parties endorsed a $400 million increase to NIH’s budget on July 31. The Senate Appropriations Committee also retained all 27 NIH institutes and centers, rejecting a White House consolidation proposal, and rejected the administration’s plan to revamp the way NIH pays universities, medical schools, and other research centers for overhead costs.

“The proposal is in the Senate, but this signals that both Democrats and Republicans have no appetite for NIH cuts in 2026 or a large reorganization, and that’s a great sign,” said Scott Delaney, a Harvard research scientist and the co-creator of the Grant Witness, a database tracking cuts.

Scott Delaney is the co-creator of the Grant Witness database. Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

Scott Delaney is the co-creator of the Grant Witness database. Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff

2. A new Trump executive order calls for sweeping changes to funding decisions.

On Aug. 7, President Trump signed an executive order aimed at reforming federal grant funding and “ending offensive waste of tax dollars.” The order states that last year, more than a quarter of new NSF grants went to “diversity, equity, and inclusion and other far-left initiatives.”

The executive order requires federal agencies to appoint senior political officials to review and approve all discretionary grants, including renewals, ensuring they align with White House priorities. Career experts and peer reviewers will continue to be involved in the process, but will no longer have the final say.

It also directs federal agencies to incorporate a “termination-for-convenience” clause that would make it easier for the government to cancel grants. The order also says that federal funding may not be distributed to programs that use racial preferences, deny binary sex classifications, support undocumented immigration, or promote what the directive deems “anti-American values.”

Attorneys at Washington, D.C.-based firm Arnold and Porter wrote in an analysis that the order is not legally binding but that it sets the tone for subsequent Office of Management and Budget guidance and potential rulemaking.

3. A new policy may limit the number of NIH grants awarded.

The NIH plans to shrink the share of grant applications it will award for the remainder of this fiscal year, which ends Sept. 30, due to a new Trump administration policy. The policy will continue into next year unless Congress steps in.

The impact weighs heavily on R01 grants, which are often awarded to universities and medical labs working on scientific research and training graduate students and postdocs, according to the Globe’s sister publication, STAT.

Driving the policy is an administration decision to change the way NIH distributes funding for multiyear grants. In the past, federal agencies have spread out funding over the life of the grants, which typically last three to five years. According to the new policy, at least one-half of the NIH’s remaining funds for supporting new projects in 2025 must be paid out up front.

“Instead of supporting five grants for one year, it’s funding one grant for five years,” Delaney said.

He added that the push to fund grants for multiple years at once is the result of many in the NIH rushing to spend funds that were allocated for this year but have not been distributed due to grant terminations and disruptions to the grant review process.

An NIH spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

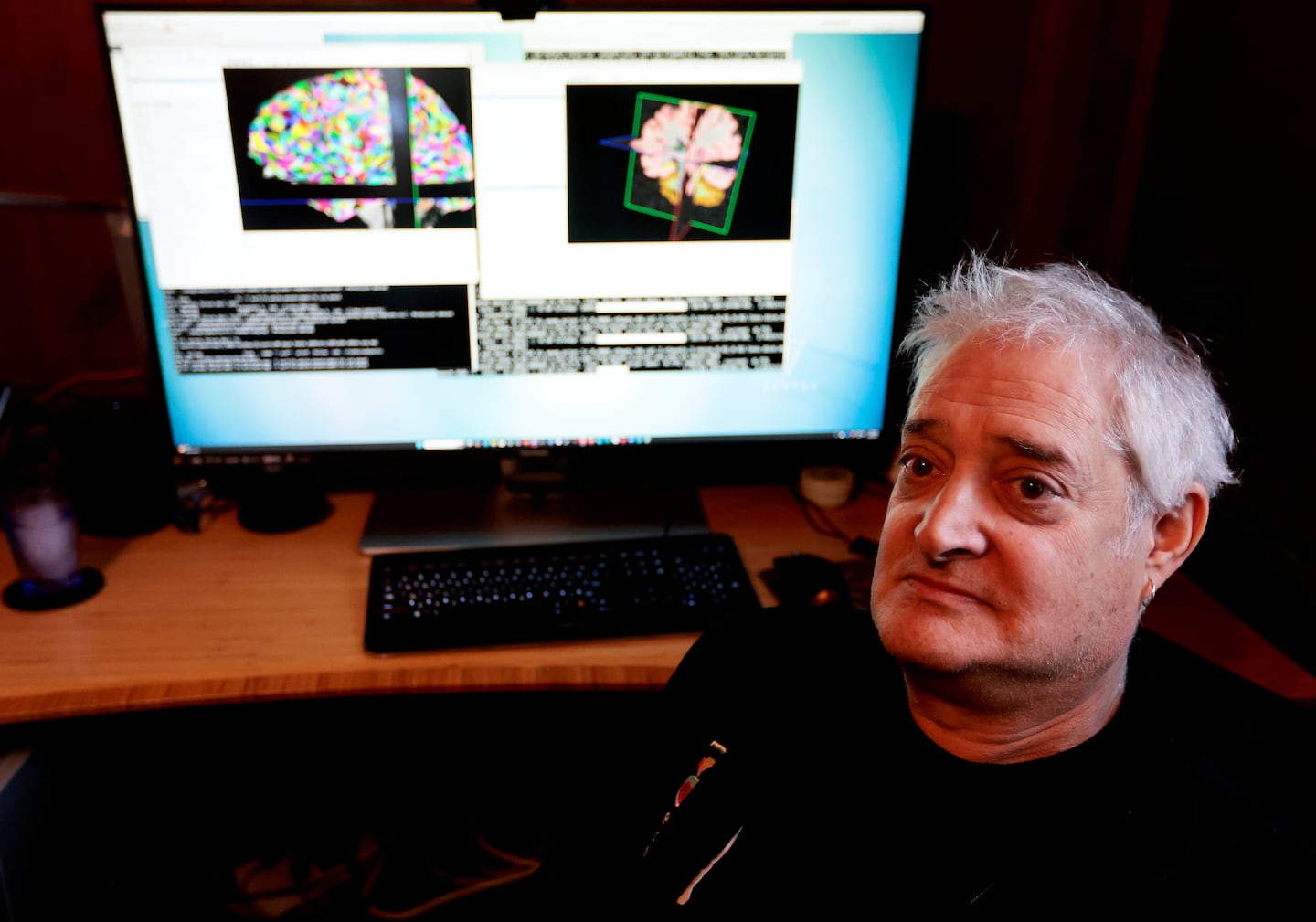

Dr. Bruce Fischl, professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, does research on the intersection of computer science and neuroradiology at Massachusetts General Hospital.Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff

Dr. Bruce Fischl, professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, does research on the intersection of computer science and neuroradiology at Massachusetts General Hospital.Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff

4. A new approach to lowering indirect costs

In February, the NIH sparked widespread panic in the research community by issuing a rule that capped indirect cost reimbursement at 15 percent — far below the typical 30 to 70 percent institutions depend on to cover infrastructure and administrative support. Previously, each research institution negotiated rates with NIH based on its documented expenses.

The measure was blocked in April by an injunction that is being litigated through the Massachusetts Appeals Court.

“This money pays for our power, the lease of our building, it’s the infrastructure we all need,” said Dr. Bruce Fischl, professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School.

The Trump administration argues the cap is to align indirect costs with those paid by private foundations and to direct more of the budget to research rather than overhead.

The administration is also trying to limit indirect cost rates in another way. The president’s August executive order directs grant reviewers to prioritize institutions with lower indirect cost rates over those with higher ones. It also encourages agencies to avoid concentrating funding among repeat recipients and instead support a broader mix of institutions.

“This may significantly reduce cost recovery for institutions with higher [indirect cost] rates, an issue that is both the subject of active litigation and Congressional review through annual appropriations and authorizing legislation,” Arnold and Porter attorneys noted.

The Joint Associations Group, a coalition of national academic, medical, and independent research institutions, proposed a new approach to calculating indirect costs. Instead of negotiating indirect cost rates with each institution, the group proposed a model that calculates indirect costs based on the total project cost, aiming for a clearer understanding of how funds are allocated and used.

5. The immigration crackdown

Since the Trump administration took office, New England has lost $3.15 billion in research funding from the National Science Foundation and the Department of Health and Human Services. The latest update includes most of the grants terminated at Harvard, totaling $2.4 billion. Of that, $2.16 billion comes from NIH awards — roughly one-quarter of all NIH terminations nationwide — and has catapulted Massachusetts to the top of the list for revoked federal research funding.

Researchers warn that these cuts threaten long-term innovation, drug development, and America’s global leadership in science.

Fischl added that the administration’s immigration policy is also slowing scientific advances.

“A significant fraction of the smartest people in the world want to come to the states, and when they come, they frequently stay,” he said. “They are a boon to our economy, but that’s drying up. People are afraid. I have postdocs that haven’t seen their families in two years because they’re afraid to go home because they’re not sure they’re going to make it back. It’s heartbreaking that these people want to contribute to our society and we’re not letting them.”

Sarah Rahal can be reached at sarah.rahal@globe.com. Follow her on X @SarahRahal_ or Instagram @sarah.rahal.