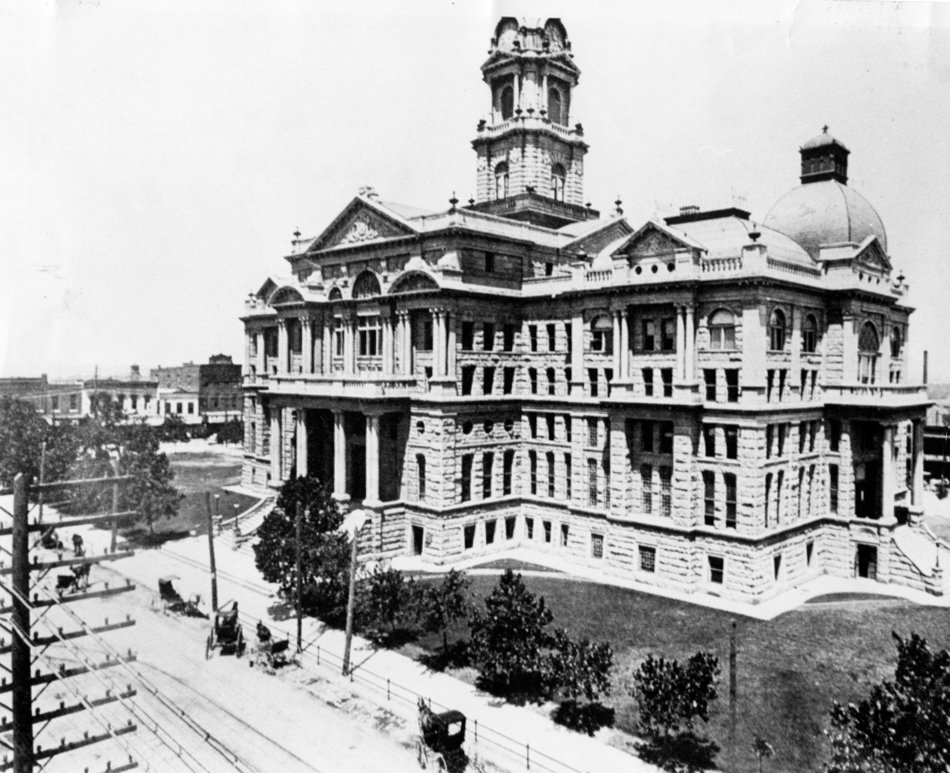

One of the most notable episodes in Fort Worth lore is the 1894 Tarrant County Commissioners Court election.

As the story goes, irate voters took out commissioners who voted to approve bonds for the construction of the 1895 Tarrant County Courthouse. To many, the lavish public expense was an insult to residents struggling through the economic hardships of the Panic of 1893.

So, voters imposed their own term limits, tossing out the offending commissioners on their backside and into a minefield of saddle chips.

Only it didn’t happen. When I went to research it, I couldn’t find a thing. Stumped, I went to the experts.

It’s all a myth, this thing about angry mobs with pitchforks pulling levers against them damn crazed spenders downtown writing checks in defiance of the will of a people surviving on beans.

“This is one of those many instances in local history where fiction gets told so often it becomes an accepted fact,” says Quentin McGown, an authority on local history and author of four books about Fort Worth. “A lot of us have grown up with the story, and some of us have been working to debunk it.”

If there was a taxpayer revolt over the courthouse, it left no tracks in the run-up to the November 1894 election, Fort Worth historian Richard Selcer points out. By then, the fight was already over. The real battle had played out in the May Democratic primary, when George W. Armstrong unseated County Judge R.G. Johnson. Johnson, suitably chastened, announced his “retirement” at the end of the term.

Armstrong had an, ahem, interesting story. His grandfather signed the Texas Declaration of Independence and went on to survey the original state boundary with the United States. A graduate of UT law school, Armstrong, who also later ran for governor of Texas, was an early advocate of cooperation between Dallas and Fort Worth in civic development.

His reputation never got any better.

Armstrong, who amassed a fortune in oil, banking, steel, and real estate, gained national headlines in 1949 when he offered Jefferson Military College in Mississippi a large endowment — reportedly $50 million — to teach the “superiority of the Anglo-Saxon and Latin American races” and exclude Blacks, Jews, and Asians from the school.

But back to those courthouse bonds. They’d been voted in years earlier. By 1894, that ship had sailed, Selcer says. In fact, just a month before the election, commissioners greenlit extra funds to dig a tunnel from the courthouse to the jail across Belknap Street. Nary a discouraging word. And while voters were still paying off a city bond for the waterworks, nobody raised a ruckus about that either. If bonds were the hill to die on, wouldn’t both have drawn fire?

The real drama was the pitched battle between the Democrats and the Populists, each side vying for control of county government. The Democrats nearly swept the table. At a September campaign stop, Armstrong and Populist S.O. Moodie traded “virulent personal attacks,” according to reporting at the time.

But not a syllable deployed about courthouse costs.

After the dust settled, the Gazette rolled out the red carpet for the winners, hailing their Democratic pedigree — “Democrats know how to govern” — noting only two officials were stepping down and sending them off with compliments on their “patriotic and high-minded” service.

No scandal. No outrage.

The reality, Selcer says, is that turnover on the Commissioners Court was routine. Most figured two years in public service was plenty.

McGown, however, has a theory about how this urban legend came to be.

Commissioner Henry R. Wall of Grapevine held a seat on the court from 1891 until his death in 1919, except, that is, for one term. His obituary in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram gave an explanation for why he lost in 1893.

“His first term as county commissioner began in 1891. He was defeated for reelection two years later because he had been criticized by his opposition for building the present county courthouse. His opponents believed the building to be too large and too expensive for the county and were against issuance of the bonds.”

The Dallas Morning News echoed this belief — likely Wall’s belief — that his defeat was caused by illogical voter behavior: “Many of his constituents in the Grapevine precinct opposed the bond issue at that time.”

Both newspapers noted that Wall lived to see the bond issue retired nearly a year ago.

“I can only speculate, but I think, based on the scant evidence, that one man’s explanation for his political defeat fueled a legend that just stuck,” McGown says. “It is certainly more entertaining than a mundane election transition