Adam Barbanel-Fried believes in the power of personal connections. As director of the nonprofit Changing the Conversation Together for Progress, he focuses on training “deep canvassers.”

“We really try to connect with voters openly, nonjudgmentally, and by the telling and eliciting of personal stories,” he said. “We’re connecting emotionally in this very open space and we are then able to have a much more impactful conversation. And it’s been shown in randomized control trials to be the most effective form of voter persuasion that’s ever been measured.”

Barbanel-Fried’s volunteers take a unique approach. While traditional canvassers often reach out during the last few weeks of a political campaign for quick, transactional conversations, he said, CTC’s volunteers focus on year-round, vulnerable and open conversations.

“Deep canvassing is a very different approach,” he said. “It’s face to face. It is a form of voter engagement where we try to connect with folks authentically and vulnerably and as opposed to trying to approach people who may not see the value of voting or engaging in politics or your perspective. We really don’t try to approach them with a goal of trying to reason or rationalize or argue or go through issue talking points.”

The strategy

CTC launched in 2017 to connect with swing voters in Staten Island, N.Y. The group of canvassers focused its efforts on Max Rose, a Democrat running for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Barbanel-Fried said the goal at the time was to have “nonjudgmental” dialogue around contentious topics.

Rose won a district that had voted for President Trump in 2016.

“It was the first time Staten Island had flipped in a midterm for many years, and that story went viral, and we were invited into Pennsylvania,” he said. “We were happy to be invited in because we knew we wanted to use CTC’s efforts in an important part of the country. There are several key areas in the country that are continuously seeing these very close elections.”

The group started deep canvassing in Pennsylvania ahead of the 2020 election. They continued to canvas in Philadelphia ahead of the 2022 and 2024 elections, focusing on areas like West Philly – where Barbanel-Fried said the impacts of policy decisions are often felt.

“After this past election, this current year, we really started talking to folks about the cuts to Medicaid and other social services,” he said. “We were canvassing in West Philly for the last series of years, and the impact that is going to be felt by people in neighborhoods like West Philadelphia or Philadelphia, or all the lower-income neighborhood communities around the country, is huge, and yet there’s this huge universe of people who either they don’t know or if they know, they don’t know how serious it is.”

In the 2024 election, the group canvassed for voters to support presidential candidate Kamala Harris. The group’s focus wasn’t to change people’s minds if they were set on their vote, Barbanel-Fried said, but to help educate residents about politics and to help encourage nonvoters to register to vote.

A canvasser knocks on doors in West Philly ahead of the 2024 presidential election (Photo courtesy of Changing the Conversation Together)

A canvasser knocks on doors in West Philly ahead of the 2024 presidential election (Photo courtesy of Changing the Conversation Together)

Barbanel-Fried recalled an example of the group’s efforts in a conversation with a woman named Faith sitting on her porch with her partner in West Philadelphia.

The conversation often starts by testing the resident’s willingness to vote.

“I said to her, ‘How likely are you to vote on a scale of zero out of 10?’ ” he said. “And she said, ‘Probably a four.’ So four, obviously, that’s a very low chance. I asked, ‘Why is that the right number for you, Faith?’ And Faith says, ‘Well, I don’t really get involved in politics very much.’ That is when I, as any of our canvassers would, start telling a personal story.”

The group is trained to avoid lectures or lists of facts at that moment, he said, because this isn’t very effective.

“One option is I could just jump into a lecture and say, ‘This is why you need to vote,’ ” he said. “But we believe that that doesn’t work. No one likes to be lectured. The reason people do or don’t do things, it’s not necessarily a rational thing.”

The stories are often unconventional, Barbanel-Fried said, but have one theme in common – love. In this situation, he chose a story about a heartwarming present he received from his wife.

“I came home one summer and it was my birthday and there was no one around,” he said. “She had sent me this wonderful gift that was handmade. The packaging itself was so elaborate, with streamers and drawings and poetry and songs and just very celebratory things. And I was so surprised. It meant a lot to me.”

The point, he said, is that sharing this kind of personal story and showing vulnerability can help others feel more connected to you.

“This is sort of a universally relatable story, and Faith said, ‘That’s really sweet,’ ” he said. “And I asked her, ‘Well, what about you? Who are some of the people who you love?’ And she told me about her sister, and she started opening up with a story about her sister who really showed up for her right after her mother died.”

Barbanel-Fried shared that he could see that Faith valued “caring for others” during difficult times. That’s when he shifted the conversation back to politics.

“I said to her, ‘And that’s what I think politics is basically about. There’s a world of people who are advocating that. We don’t take care of the most of the least fortunate, but I think that people like you and me and most people in the world, we care about each other.’ ”

He said the exchange ended with Faith saying she was now a 10 when it came to likelihood of voting.

The conversations that canvassers have tend to invite “authenticity” rather than a set script, said Elizabeth Eagles, a volunteer with CTC.

“In the types of conversations that we have, deep canvassing is leading with your humanity, rather than a specific agenda, in a way that really invites an authentic conversation with someone,” she said.

Eagles came to CTC with more traditional canvassing experience. She said the flexible nature of the organization’s approach also makes it stand out from other canvassing methods.

“Unlike most of the canvassing I’ve done in the past, where you were really wedded to your ‘knock’ list, like you wanted to talk to the precise individual who was on your list, CTC actually encourages you to strike up a conversation if you encounter somebody on the street, so that is a sort of more organic approach,” she said.

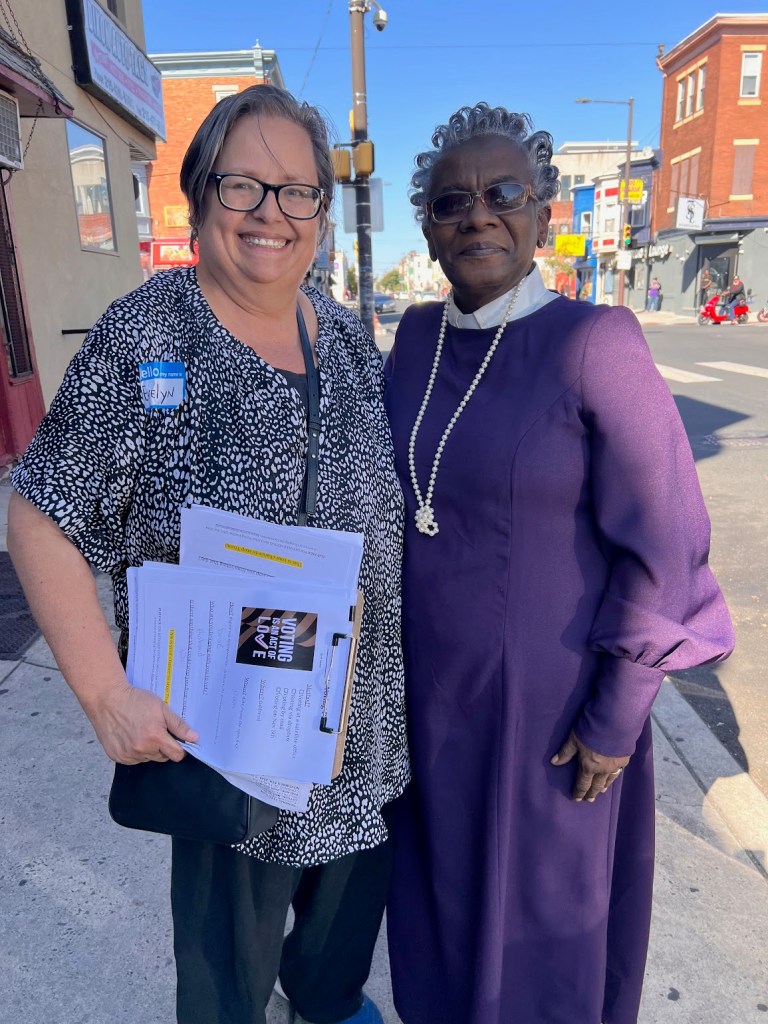

A CTC canvasser stands with a member of the community who has decided they are now a “10” on a scale of 1-10 in likelihood to vote (Photo courtesy of Changing the Conversation Together)

A CTC canvasser stands with a member of the community who has decided they are now a “10” on a scale of 1-10 in likelihood to vote (Photo courtesy of Changing the Conversation Together)

Impact

The organization has also measured the impact of its canvassing efforts. In 2020 and 2022, the voters that CTC spoke with voted at rates 10-15% higher than their neighbors.

In 2024, the voting rates of those who were deep-canvassed by CTC were 22% higher than the voting rates of their comparable neighbors.

Barbanel-Fried said the group’s goal is not to change voters’ minds. If a voter is already set on their vote or is unwilling to engage, canvassers are taught to move on.

“There are some people who’ve been pretty burnt in life, or have really become very cynical about the world,” he said. “And who am I to judge that there’s a world of people who don’t see it the way that we do, and my goal is not to persuade someone who I can’t persuade. But there’s a world of people out there. And I would say [those who are hateful or hostile] are not the majority. I would say they are a slim minority of the people we encounter.”

Deep canvassers are taught to roleplay and figure out solutions in real time, he said.

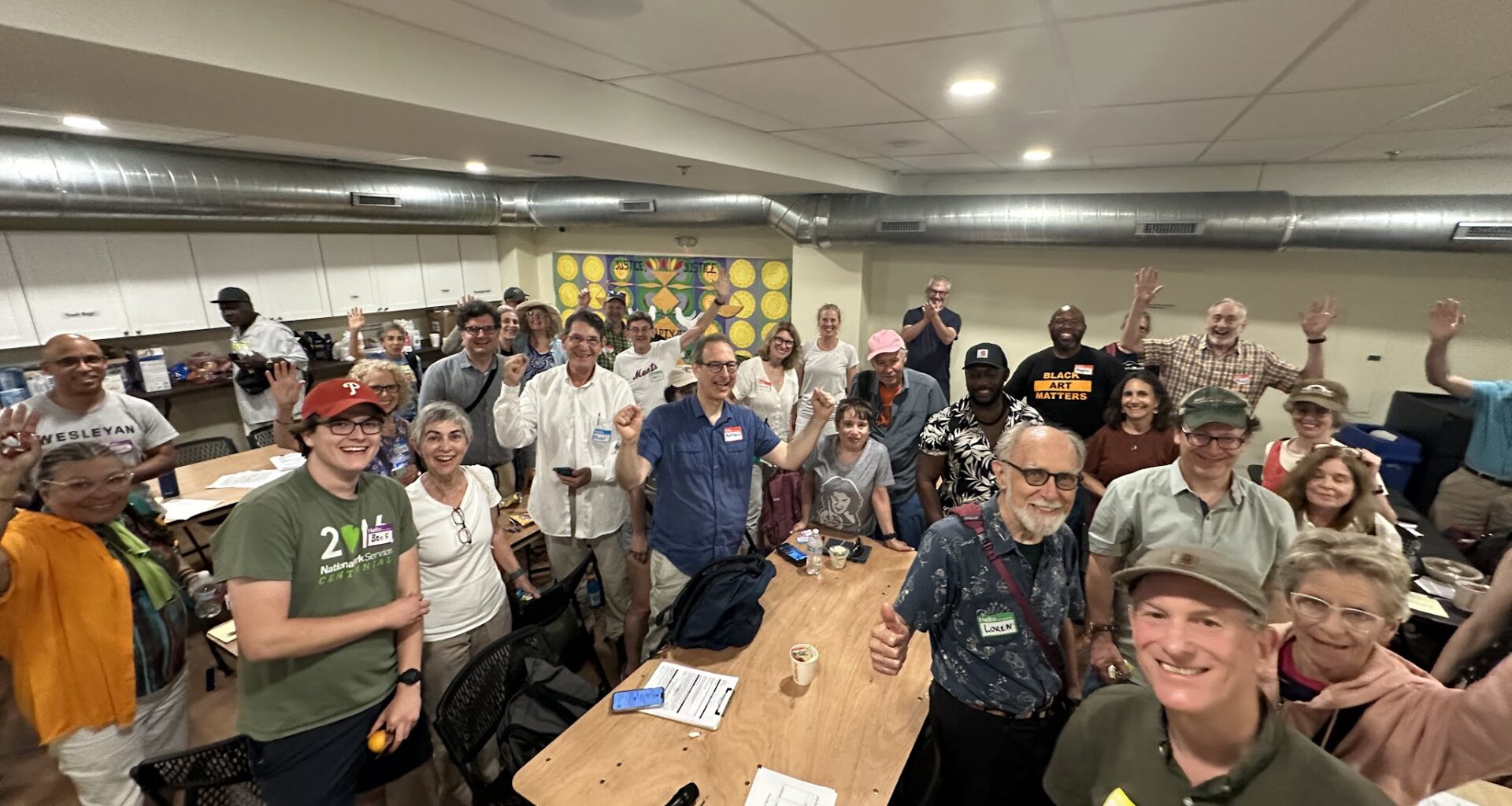

CTC members meet to train and roleplay situations before going out to canvass (Photo courtesy of Changing the Conversation Together)

CTC members meet to train and roleplay situations before going out to canvass (Photo courtesy of Changing the Conversation Together)

The group currently does monthly canvassing sessions in West Philly, Eagles shared. Groups of five or six canvassers will go out in pairs to knock on doors and talk to individuals on the street in various neighborhoods. The work has benefits for the canvassers as well.

“It doesn’t totally feel natural for me, as an introvert, to knock on someone’s door or stop someone on the street, but I think it’s important to overcome my discomfort and just press on, because there is really this kind of magic that can happen because you’re engaging in this kind of radical act of vulnerability, opening up to a stranger and then holding space for them to choose to share about who and what is important to them and their lives,” she said.

Eagles said she is often surprised by how welcoming strangers can be, recalling a heartwarming conversation she had while canvassing recently.

“I saw a young woman walking on the street and I started walking next to her,” she said. “Her body language was pretty closed off, and she was not really giving me an in. But I ended up talking about my daughters, who are 13 and 11, and how I really feel a responsibility for the kind of world that they are growing up in.

“And I could feel her body language soften towards me, and she said, ‘I have a daughter too.’ And then she really listened, and she told me about her daughter as we walked. And at the end of the conversation, she stopped and looked me in the eye and she said, ‘Thank you for being out here and doing this.’ ”

The group will continue with monthly canvassing, even outside of election season, Eagles said. As election season nears, there will be increased canvassing efforts.

Eagles is a believer in the approach, and felt it was a positive force in the 2024 election.

“So, in talking about love and sharing stories about people we care about, and sort of distinguishing the choices we had in that presidential election, I think it helped people recognize and say ‘I am going to vote,’” she said. “Like, it’s an act of hope. It’s an act of resistance.”