From the spring of 2008 until the fall of 2010, the Dallas Independent School District did just about everything it could to stop W.H. Adamson High School from becoming a historic Dallas landmark. It was a particularly ugly battle, as far as these things go, pitting the graduates of the former Oak Cliff High School, built in 1915, against the DISD administration, including a superintendent, Michael Hinojosa, who began his career as coach and educator at the school he was trying to raze.

Glenn Straus, president of the Adamson Alumni Association at the time of the tussle, told me Thursday that it got to the point where he couldn’t sleep most nights. “I was so worried about Adamson being torn down,” said Straus, retired at 87 and now living in Poetry, Texas. “It was not pleasant.”

In June 2011, the association got what it wanted — and more. And it might all have been for nothing.

The original Adamson, sitting next door to its sprawling replacement, became a Dallas landmark, with all the protections (allegedly) afforded such historic structures. Shortly thereafter, Dallas’ second-oldest public high school was added to the National Register of Historic Places. A year later, a Texas Historical Commission marker was planted in front of the building, noting its place, at the time, as “the oldest continuously operating high school” in the district.

News Roundups

When I went to the campus on Thursday, that historic marker was slathered in yellow spray paint. It’s been like that for months.

The front of old W.H. Adamson High School, which appears to have far more boarded-up windows today than it did just eight months ago

Robert Wilonsky

I walked around the original school on East Ninth Street, which is surrounded by vague vestiges of a chain-link fence erected a couple of years ago. A gate, which is supposed to be locked to keep people from entering the back of the campus, was wide open. It’s decorated with “NO TRESPASSING” and “RESTRICTED AREA” signs. Most of its windows are broken, boarded up or just wide open — the result, I was told, of kids throwing rocks at the school and of the unsheltered getting inside.

The campus — designed by a St. Louis architect, William Ittner, who has 34 other structures on the National Register of Historic Places — now looks like any other derelict, abandoned, battered and bruised building, just another neighborhood eyesore. Because that’s all it is now, a languishing landmark being destroyed in slow motion – demolition by neglect, in other words, a violation of the very ordinance meant to preserve and protect Adamson.

“We are fearful it will be mysteriously burned or just fall down one day,” alumni association vice president Linda Pauzé told me Thursday. She worked for the district for 38 years, 18 of those spent teaching English at her alma mater, and still lives nearby, in North Oak Cliff. “It makes me sick to my stomach. That’s why I quit driving by the building. I couldn’t stand to see it deteriorate.”

But that’s the idea. I’m pretty sure that’s the plan.

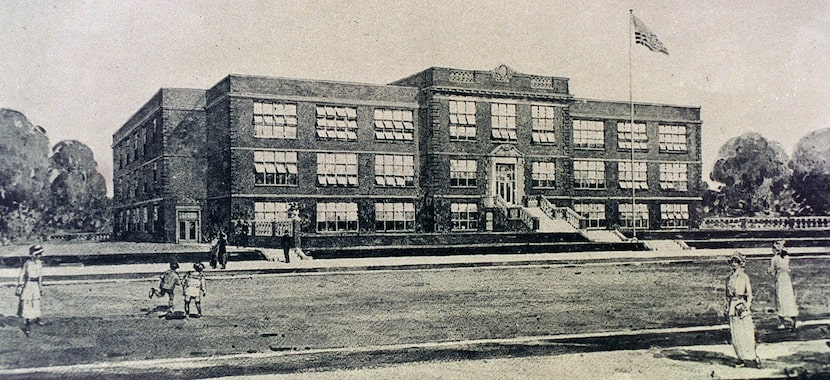

Drawing obtained from DISD vault of the new Oak Cliff High School, now W.H. Adamson High School, in 1916.

Randy Eli Grothe / 99071

DISD, which has long been loath to spend money on preserving shuttered schools no matter how historic, says it has no choice but to tear down the building, insisting that numerous efforts to convert the moribund Adamson into a “Digital Arts and Creative Technology campus” have failed repeatedly because the building is too far gone — and, now, too expensive — to save. In letters and documents sent to the alumni association and Dallas’ Landmark Commission, DISD officials say the building is an “imminent threat to public health or safety,” and that it will cost “more than $102.5 million to shore the building so it can be repurposed.”

In May, several district officials went to Dallas City Hall to begin pleading their case to a very skeptical Landmark Commission, which would have to approve a demolition. A month earlier, a Landmark task force said it could not support such a request, and suggested this was a clear case of demolition by neglect.

Landmark wouldn’t go that far — yet — but commissioners said they were concerned that the district hadn’t done everything it could to at least preserve the building.

District officials said they’ve spent $6 million on site studies and designs for a future arts magnet campus, but added that they couldn’t find contractors willing to do the work given the building’s unsafe conditions. The district’s chief construction officer, Brent Alfred, also told the commission that “sometimes teenagers are sneaking in there just to be, you know, teenagers,” and that he didn’t think the campus was safe “because people may be hiding in there.”

Commissioners wanted to see more proof the building was unsalvageable, which the district said it will provide when it comes back for a demo permit. The commission determined that if the campus could at least be properly secured, then it would no longer be “an imminent threat.” Yet the property remained unfenced and unprotected as of Thursday. Several members of the alumni association with whom I spoke in recent days can’t help but think that’s intentional, to hasten its demise.

W.H. Adamson was built in 1915. Whether it survives until 2026 is another question.

Robert Wilonsky

Adamson boasts an impressive roster of alumni, among them former Speaker of the House Jim Wright, singer-songwriters Ray Wylie Hubbard and Michael Martin Murphey, and E. King Gill, Texas A&M’s original 12th Man. But the association isn’t merely about nostalgia: It maintains a $2 million endowment for scholarships doled out each year to Adamson grads, and keeps in close contact with those recipients.

Alfred reached out last year with a missive seeking the association’s counsel on how to best proceed. Alfred said the district had two options: spend that $102.5 million, which it doesn’t have, or “demolish the façade, since it poses a threat to public safety and replace it with a memorial/green space to honor the school’s unique legacy and celebrate the rich history of Adamson High School.”

He said he was open to other suggestions. A DISD spokesperson told me Thursday that could include selling the building to a developer, as it did in 2011, when the landmark 123-year-old Davy Crockett School on Carroll Avenue, likewise suffering from demolition by neglect, was eventually reborn as 52 luxury apartments now called The Principal Residences.

But the association and preservationists believe the district has already made up its mind. Again.

The alumni association began its first fight to save the old campus in March 2008, when it got word the building would be razed and replaced with a replacement next door. Within two months, they recruited preservation architect Marcel Quimby and asked the Landmark Commission to consider adding it to Dallas’ relatively short list of landmarks. The commission voted unanimously to move forward, which would have paused demolition for two years. That proved to be the first bell in what became a bruising fight between the district and its former students that lasted three years.

District officials say kids have been getting inside the 1915 W.H. Adamson campus, which the city landmarked in 2011. One official told the Landmark Commission in May that he didn’t think the building was safe “because people may be hiding in there.”

Robert Wilonsky

Local architecture firm Corgan told the district Adamson was in lousy shape — and had been for decades — and that it should be razed, with a few surviving scraps repurposed for the new campus. The district insisted that the alumni’s demands would add tens of millions to the new school’s final price tag. In September 2009 the school board passed a resolution that said it “opposed and rejected” any attempt by anyone to landmark Adamson.

In the fall of 2010, the Landmark Commission’s Designation Committee decided that Adamson belonged on the landmark list, which the DISD opposed until, suddenly, it didn’t. In November 2010, it suddenly withdrew its opposition and said it would begin working with City Hall “to come up with a mutually agreeable long-term strategy” for the building.

Yet here we are. Again.

I asked City Attorney Tammy Palomino on Thursday if her office has ever spoken with the district about the state of old Adamson. She referred me to code compliance and the Office of Historic Preservation, and said only that “to date, the City Attorney’s Office has not received a referral from code enforcement.”

But it’s funny how things work in this town.

Shortly before I sent this piece to my editor Friday afternoon, I got a call from an old friend at the district who I’d been pestering about the state of Adamson. He told me crews were headed out there to remove that spray paint from the historic marker and look into putting up another protective fence.

None of which will spare the school, of course. But these days, it’s amazing how far just a little effort — like, the bare minimum — will go.