John L. Campbell could not have anticipated what he started.

Campbell, a professor of mathematics, natural philosophy, and astronomy at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana, wrote to both the Smithsonian Institution and the Mayor of Philadelphia in December 1866, suggesting the country hold a World’s Fair in Philadelphia in 1876, which would also commemorate the 100th anniversary of the nation’s founding.

Philadelphia took him up on his suggestion. The rest, as they say, is history. The fair was a smashing success, celebrating the nation’s spirit as well as its industrial and entrepreneurial genius — it’s where Alexander Graham Bell introduced the world to the telephone — and eventually led to two additional national “birthday parties,” which will be covered in later installments in this series, as well as another coming in 2026. It also served as an important inflection point in the path toward women’s rights.

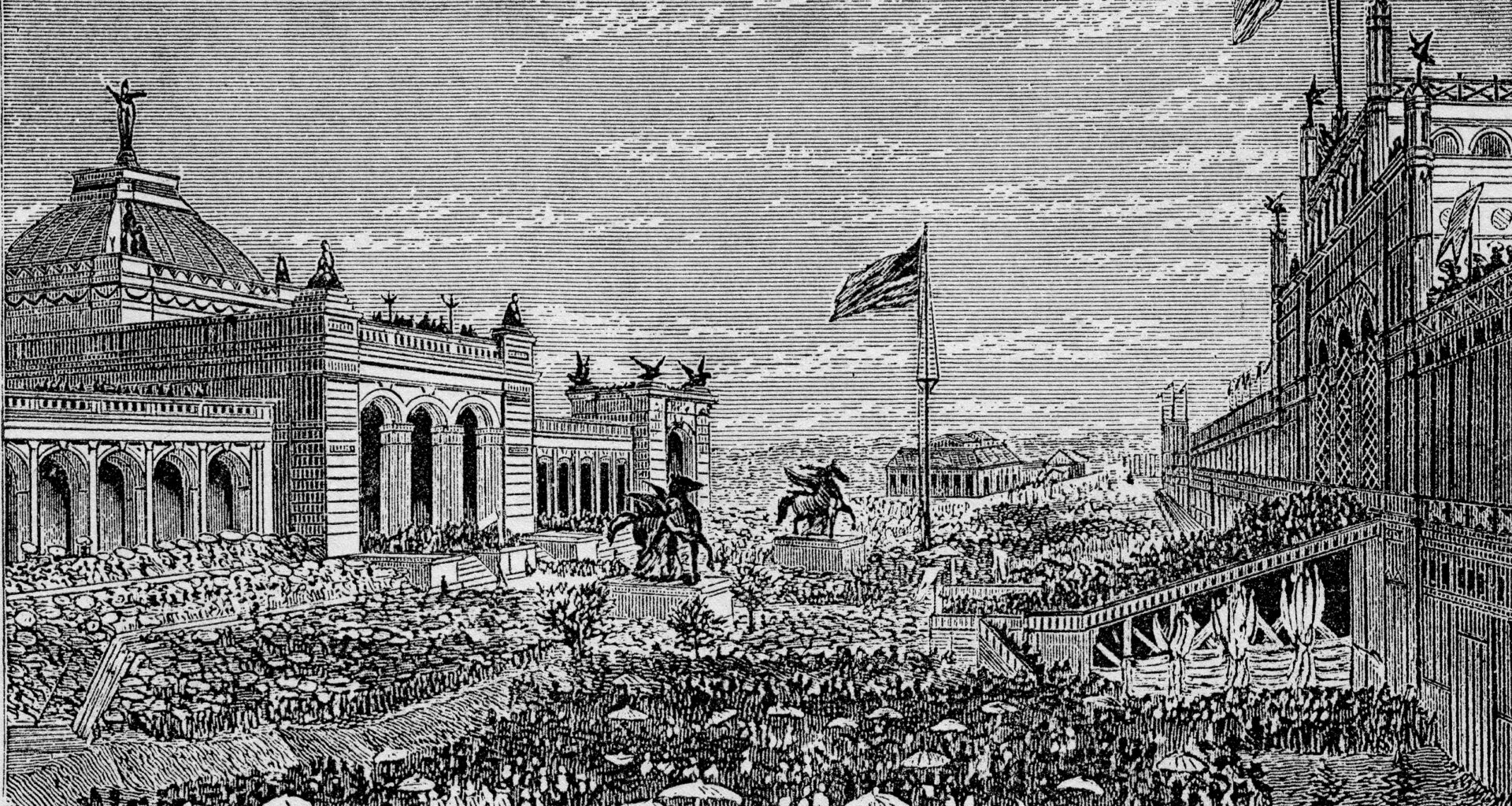

But first, let’s return to 1876, when at least 9.8 million people paid 50 cents to attend the fair, held on the Fairmount Park grounds, then the largest urban open space in the nation. An additional two million people attended but were not charged for tickets.

President Ulysses S. Grant was on hand on May 10, 1876 to open the event, along with Brazil’s Emperor Dom Pedro II. Grant was not in the city on July 4 of that year, much to Philadelphia’s consternation, but he did attend the closing ceremonies in November. The Centennial was considered a success – it did not lose money (it even made a tiny profit) and it showed Americans what the future would hold.

Competition for the party

Looking back, celebrating the birth of America on its 100th birthday in Philadelphia might seem a no-brainer, but New York and Boston both made efforts to host the party, according to Lori Salganicoff, an urban planner and self-described “Philadelphia enthusiast.”

“There had been some jockeying by some places, New York in particular, to host it,” Salganicoff said. “Initial public discussion and dissent over the exhibition site cooled media interest in the celebration, with some advocating for Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, New York and St. Louis over Philadelphia. This, and the financial panic of 1873, challenged fundraising and organizing, among other things.”

“I found an entertaining, salty advertisement out of New York City, wrongly describing that Philadelphia was an inferior choice compared to New York,” she continued. “But in addition to being the city with the ‘room where it happened,’ Philadelphia offered the site of Fairmount Park, an excellent transportation network, citywide charm and had a precedent for a smaller fair in 1864 that succeeded due to a combination of public, private and commercial efforts. New York’s own fair precedent had not been successful.”

In 1871, with support from prominent businessmen such as John Wanamaker, local political leaders and the Franklin Institute, the city and state successfully petitioned Congress to authorize the Centennial and set up a commission to oversee planning and implementation, Salganicoff said.

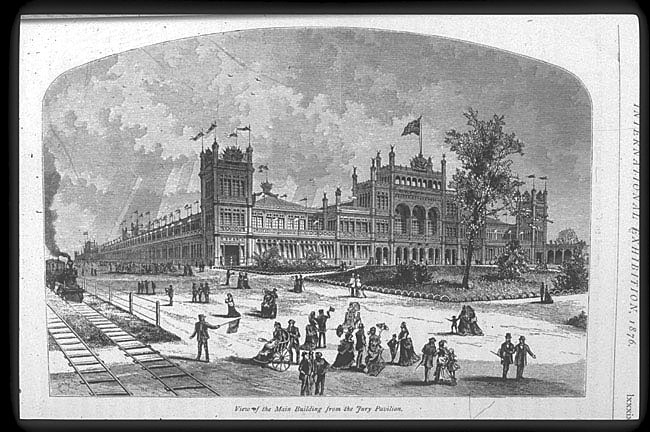

The main exhibition building, which enclosed more than 21 acres, was the largest building ever built when it was opened for the 1876 World’s Fair. (Smithsonian Institution)

The main exhibition building, which enclosed more than 21 acres, was the largest building ever built when it was opened for the 1876 World’s Fair. (Smithsonian Institution)

That year, Congress passed legislation to hold an “Exposition of American and Foreign Arts, Products and Manufacture,” establishing the U.S. Centennial Commission after it was presented with a plan that proposed a theme of patriotism, American industrial skill and national unity. President Grant appointed commissioners from each state and territory, with recommendations from their governors.

The Centennial, she said, “formally named the ‘The International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures and Products of the Soil and Mine,’ was different from prior world’s fairs as its original stated purpose was not a commercial one, but rather a commemoration to the founding of a nation of free people, and to progress in human ingenuity — an exhibition of resources and resourcefulness.”

Among the exhibitors at the fair was Bell, who showed off his latest invention, the telephone, for the first time ever.

The right arm and torch of Statue of Liberty as displayed at the 1876 exposition. The Statue of Liberty was erected in 1886. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

The right arm and torch of Statue of Liberty as displayed at the 1876 exposition. The Statue of Liberty was erected in 1886. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

Congress had originally not appropriated any funds, having left that to the U.S. Centennial Commission, but it was not up to the task. The City of Philadelphia kicked in $1.5 million, Pennsylvania granted $1 million, and Congress voted for a “loan” of $1.5 million, which the city thought they would not have to repay, but eventually it was paid back. Congress also created the Centennial Board of Finance in June 1872 to raise funds through the sale of stock.

Almost 250 buildings were constructed for the event, across 236 acres in Fairmount Park. Four remain today.

More than 30 countries sent contributions to the Exhibition, and rulers from as far away as Brazil traveled to Philadelphia.

The arm and torch of the Statue of Liberty was put on display at the Centennial. The statue was completed and erected in New York in 1886.

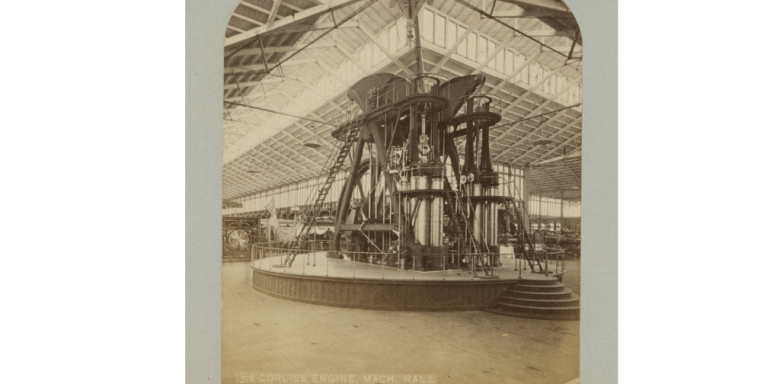

The centerpiece of Machinery Hall and the most popular exhibit was the Corliss engine. Novelist William Dean Howels wrote of it in “Harper’s Weekly” magazine: “(Rising) loftily in the center of the huge structure, an athlete of steel and iron with not a superfluous ounce of metal on it.”

The Corliss Engine was among the inventions that astounded visitors. (Library of Congress)

The Corliss Engine was among the inventions that astounded visitors. (Library of Congress)

“This was a time of great scientific, transportation and industrial progress around the world, and all were hungry to learn from and share their own proud innovations with others. Also at play were political efforts to reconstruct the U.S. after the Civil War, political reunification of the North and South, the panic of 1873, and the burgeoning age of industrialism,” she added.

Philadelphia’s renowned artist Thomas Eakins painted The Gross Clinic for the Centennial. It pictured a medical operation and is considered one of the iconic pieces of American art, but was denied installation at the Centennial Art Gallery (later Memorial Hall) because it was considered too graphic. Instead, the painting was hidden away in a corner of the U.S. Army Post Hospital exhibits elsewhere at the fair.

Women and the Centennial exhibition

According to Salganicoff, another significant political aspect was the treatment and presence of women in the Centennial. For leaders of the women’s rights movement, there was a tension over whether to make the best of what was offered by focusing on women’s achievements, or use the opportunity to fight for women’s right to vote and hold public office.

“Members of the National Woman Suffrage Association — led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage — thought avoiding political activism during the Centennial was a mistake as it acquiesced to a patriarchal social order. They saw the Centennial as an opportunity to draw attention to women’s suffrage, and members of the group crashed the July 4 festivities at Independence Hall to present the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Women’ to a surprised Vice President Thomas Ferry,” Salganicoff added.

An image of the Women’s Pavilion at the 1876 World’s Fair. (Courtesy of Wikimedia)

An image of the Women’s Pavilion at the 1876 World’s Fair. (Courtesy of Wikimedia)

Another group of women, she said, led by Elizabeth Duane Gillespe, a great-granddaughter of Ben Franklin, took advantage of this as an opportunity for better control and impact within imposed constraints, raising funds for the building and exhibiting of inventions and creative works that many found revelatory. More than 75 women exhibited inventions for which they had secured patents; the steam engine powering the exhibits in the Pavilion was run by a young woman named Emma Allison.

“The main activity of this Women’s Centennial Committee was to organize a special exhibit of women’s work, for which ample space had originally been reserved and promised in the Main Building. In June 1875, however, the men of the Centennial Commission advised female organizers that this display was no longer possible. Requests from foreign exhibitors had multiplied so rapidly that the area allotted to each applicant had to be substantially limited.

“With less than a year before opening, they were told that if women hoped to exhibit their work, they would have to erect a separate building for its display and bear the entire cost themselves,” Salganicoff said.

“The Women’s Centennial Committee set in motion its successful fundraising machinery for its own building. Appeals were made, through local committees, to the women of the various states and territories. The response was so favorable that in less than four months the entire cost of $31,160 for the Woman’s Building had been raised and construction begun. Thousands of additional dollars were obtained to meet related expenses for the rest of the fair. Promoters, for instance, paid famous composer Richard Wagner $5,000 in gold to compose the ‘Centennial Inauguration March,’ and they sponsored a woman’s journal, a kindergarten, a Catalogue of Charities, a national cookbook, and a series of symphony concerts,” she said.

“From the start, this group of Centennial women expressed their greatest concern over the question of women’s advancement. They published The New Century, an eight-page weekly paper, printed at the Woman’s Building and financed entirely by the Women’s Centennial Committee,” said Salganicoff. “This pro-feminist journal, edited by Sarah Hallowell of Philadelphia, attacked the cultural and institutional barriers which prevented women from obtaining equality and justice.”

The paper called for women’s financial autonomy and insisted upon equitable compensation and opportunity for all female endeavors.

Memorial Hall, built for the 1876 World’s Fair, now is home to the Please Touch Museum. (Library of Congress)

Memorial Hall, built for the 1876 World’s Fair, now is home to the Please Touch Museum. (Library of Congress)

A celebration of progress

In the “Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition,” James D. McCabe wrote of his hope that America’s material progress would be hastened by the exhibition:

“The farmer saw new machines, seeds and processes; the mechanic, ingenious inventions and tools, and products of the finest workmanship; the teacher, the educational aids and system of the world; the man of science, the wonders of nature and the results of the inventions of the best brains of all lands. Thus each returned to his home with a store of information available in his own special trade or profession.”

After it ended, most of the exhibition’s buildings were torn down or moved. Memorial Hall and the Horticulture Hall remained. The horticultural building was demolished after suffering damage from Hurricane Hazel in the 1950s. Memorial Hall is now the home of the Please Touch Children’s Museum.

Two smaller buildings, referred to as “comfort stations,” are now used for storage. Of the 27 states that sent houses, only the one from Ohio is still standing. Made of marble and other stones culled from 21 quarries in the state, each quarry placed a stone with its name engraved in it on the house. Today, the building is the home of the Conservancy of Fairmount Park.