In a community with many needs, San Antonio and Bexar County are prepared to commit roughly $800 million in public dollars to an overall $1.3 billion Spurs basketball arena.

Critics argue that public resources should be spent addressing more pressing concerns for the average resident — like flood control, affordable housing and transit.

Meanwhile city and county leaders contend that most of the arena’s public funding would come from taxes on new development that wouldn’t exist unless it’s built, plus some state dollars and visitor taxes that can only be used for projects like arenas, stadiums and convention centers.

At the heart of the issue is a complicated funding scheme that both critics and supporters agree hasn’t been thoroughly explained to the public.

It’s also reflective of a new strategy San Antonio has been testing to incentivize development without putting a burden on taxpayers — but that critics warn could potentially backfire.

Total Spurs arena cost: $1.3B+

$311M from Bexar County

$489M from San Antonio

$500M + any remaining from Spurs?

Soon voters will be asked to weigh in on a portion of the NBA arena’s public funding, $311 million in county venue tax dollars, on the Nov. 4 ballot.

Another $489 million is expected to come from the city, which says it can spend the money without a public vote. And the remaining $500 million-plus would be paid for by the Spurs’ ownership.

The San Antonio Report broke down the pools of public funding and how they would work.

Bexar County’s $311 million ‘venue tax’

What is a venue tax?

The county is asking voters to use its “venue tax” to help fund the arena, increasing the tax on hotel rooms from 1.75% to 2%, and extending an already existing 5% tax on rental cars.

A venue tax is a tool created by state statute that allows cities and counties to finance an array of community and sports projects through fees that fall primarily on visitors instead of residents.

Texas’ Local Government Code says the money can be used for arenas, coliseums, stadiums, parks, aquariums, music halls and watershed protection, among other projects, but the Texas Comptroller must certify that a project qualifies before voters are asked to approve the money.

In June, the county sought permission from the state to designate the new Spurs arena and county-owned facilities on the East Side as venue tax-eligible projects. The comptroller approved the plan on June 26, allowing the county to take it to voters this November.

What critics are saying:

When Bexar County pursued a venue tax election in 2008, county leaders formed a citizens advisory committee to collect feedback on the community’s needs.

Part of the money went toward upgrades at the Frost Bank Center — the Spurs’ current home — while other portions were used for youth sports facilities, the Mission Reach eco-restoration project and renovating the Alameda Theatre, among other projects.

Critics say the county could have asked the state for permission to use the money on a variety of more pressing needs, pointing to the recent June flooding that left 13 people dead as an example:

“It is unconscionable that you want to give this money for an arena when we have people dying from infrastructure or lack thereof. … Don’t tell us this money is only for arenas. … In the early 2000s, we voted on the venue tax where there was community benefit all of us,” Rena Oden, an activist with the COPS/Metro group that opposes the program, said an Aug. 5 commissioners court meeting.

What Bexar County is saying:

This time around, County Judge Peter Sakai said that just weeks after plans for the new sports and entertainment district were unveiled at City Hall, the Spurs’ owners asked him to put a venue tax election on the ballot to fund an arena with an undisclosed price.

Sakai balked and said the county would first need a plan to repurpose the Frost Bank Center. He also wanted to make good on the long-overdue development promises made to the East Side when the center was first built.

Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai speaks during a County Commissioner meeting at the Bexar County Courthouse. Credit: Bria Woods / San Antonio Report

Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai speaks during a County Commissioner meeting at the Bexar County Courthouse. Credit: Bria Woods / San Antonio Report

The county eventually made a plan to use $191.8 million of the venue tax for renovations to that facility, as well as the Freeman Coliseum and the San Antonio Stock Show and Rodeo Grounds. Those investments are expected to be accompanied by new mixed-use development at the Willow Springs Golf Course that’s still in the works.

The remaining $311 million would go to the Spurs arena — aimed at spurring new downtown development and preventing the team from moving to another city.

Unlike the city, which is using tax reinvestments, Bexar County’s taxing entities will enjoy the growth in taxable value from both the East Side developments and the new downtown sports and entertainment district — money that’s needed for a budget that relies heavily on new growth.

“I want to make sure the community understands I’m protecting the community first, and if I can, I’m going to do everything I can to keep the Spurs in town,” Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai said at a May 21 State of the County event.

San Antonio’s tax ‘reinvestment zones’

What is a PFZ?

About half of San Antonio’s arena funding is expected to come from a state-sanctioned Project Finance Zone, which allows the city to use state sales tax money from new hotels and hotel business to fund a major a sports venue or convention center.

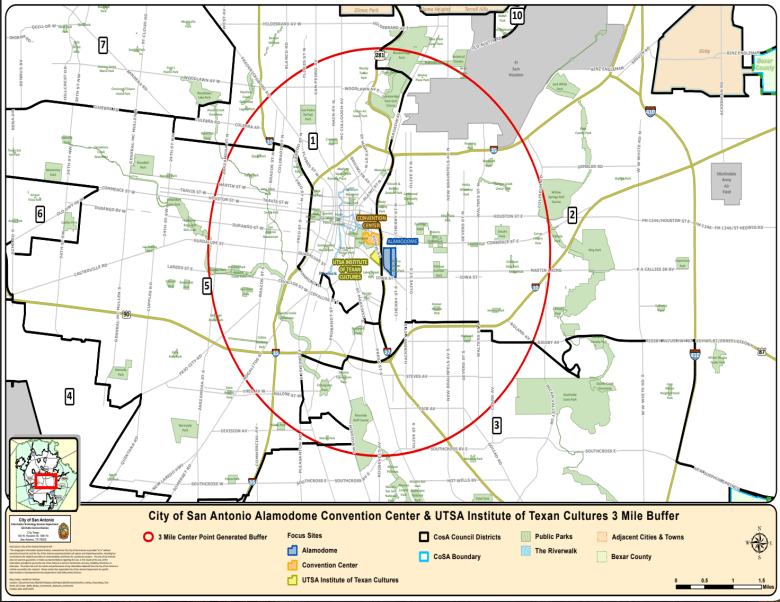

It works by drawing a three-mile radius around an approved project, and then the city collects the growth in the state’s hotel-related taxes in that area over the course of 30 years to repay bonds issued for the project.

In this case, San Antonio designated the Alamodome and Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center as its PFZ projects, and state lawmakers approved their plan in 2023.

After the county pumped the brakes on the use of its venue tax, the city amended its list of PFZ projects to a single “convention center district,” allowing the money to be spent on the Spurs arena as well. The state comptroller’s office approved the change.

What supporters say:

Texas’ five largest cities are all using PFZs to fund major projects with money that would be going to the state’s general fund — San Antonio should get its fair share.

The money can only be used for projects like arenas and convention centers, and the convention center and Alamodome desperately need expensive upgrades to remain competitive venues.

By putting some of the money toward the arena, San Antonio is leveraging state funds to bring in private development to that entire important piece of downtown.

“Project finance zone money is use-it-or-lose-it, so we might as well use it and invest in ourselves and invest in our city,” Councilwoman Marina Alderete Gavito (D7) said at an Aug. 21 council meeting.

What critics say:

Project Finance Zones lean heavily on growth projections that are often somewhat rosy.

“Accurately predicting those revenues is critically important,” Houston Chronicle columnist Chris Tomlinson wrote in a recent op-ed about such projects, because cities are obligated to repay the bonds “even if the expected tax revenues never materialize.”

As in many cities, San Antonio’s financial analysis was performed by a firm that specialized in this kind of work, but has business ties to the project.

By the analyst’s own telling, his projection makes many assumptions, like the number of new hotels and number of tickets that will be sold for events, to determine how much revenue a reinvestment zone will produce.

For that reason, Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones has been pushing the city to get a second opinion from an independent analyst with more detailed figures.

“I have been very clear that I want the Spurs here. I want a good deal. And I think we can confidently work with our community if we have confidence in the data,” Jones said at an Aug. 18 press conference. “If it corroborates what [the Spurs] put forward, then wonderful. If something is different though, then we owe it to our community to explain what that discrepancy is.”

San Antonio Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones speaks at a press conference about Project Marvel outside of City Hall on Monday, Aug. 18, 2025. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

San Antonio Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones speaks at a press conference about Project Marvel outside of City Hall on Monday, Aug. 18, 2025. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

San Antonio’s new model for TIRZ funding

What is a TIRZ?

Another big portion of the city’s funding is expected to come from a Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone (TIRZ) — which allows a city to collect the growth in property taxes from a specific area to be reinvested within that zone.

State statute allows cities to create a TIRZ in areas that are unsafe, deteriorated or causing public health problems, and then target the area for improvements.

Doing so sets a baseline for the taxable value of property within the zone, and the taxes collected off of any new development, as well as rising values on existing properties, all go to a fund for streets, sidewalks and other improvements.

A TIRZ can also include property taxes from other taxing entities, like school districts and the county, depending on how they’re set up.

San Antonio has many such zones throughout the city, and for the arena project it plans to use money from the Hemisfair TIRZ, which largely overlaps with the proposed 25-acre sports and entertainment district.

The Hemisfair TIRZ is expected to terminate in 2037, but the city says it will be extended to whatever date is needed to provide the necessary funding.

Money from another zone that includes area around the Pearl and Broadway corridor, called the Midtown TIRZ, could be used to purchase the land for the arena, City Spokesman Brian Chasnoff said Friday. The city is still exploring its options to purchase that roughly $60 million piece of property from UTSA.

What city leaders say:

Though the city has spent big on parks and other improvements around Hemisfair, development has been slow to come, so the Hemisfair TIRZ hasn’t produced much money for improvements.

Last year it generated $650,000 — the lowest figure of all the city’s TIRZ districts. That doesn’t include a new hotel that’s currently under construction and will come onto the tax roll over the next few years.

The city’s negotiated deal with the Spurs would not only add a new arena to the zone’s taxable value — but the team has also promised another $1.4 billion in surrounding development over a 12-year period.

Drone image of the Tower of Americas overlooking downtown San Antonio in August 2025. Credit: Cooper Mock for the San Antonio Report

Drone image of the Tower of Americas overlooking downtown San Antonio in August 2025. Credit: Cooper Mock for the San Antonio Report

Spurs’ ownership would also help the city purchase roughly $30 million in nearby properties to be developed for housing and businesses within the zone.

Big-picture, the city says this would allow it to fund the arena using property taxes that wouldn’t exist without the team’s investments — similar to how the Missions Minor League Baseball team is financing its new stadium in northwest downtown.

“The structure of our contribution to the arena was predicated on not using existing city resources or funds. This is that structure,” City of San Antonio Chief Financial Officer Ben Gorzell said at an Aug. 21 council meeting.

What critics say:

Researchers at Rice University’s Baker Institute say that TIRZ designations do a great job of encouraging development, but they often become some of the most valuable property in the city, creating what is essentially a regressive tax on areas outside the zone.

New housing and development within the zone requires city resources, like police and fire, but the growth in property tax revenue is being directed toward special projects within the zone, instead of boosting the general fund for the entire city.

In San Antonio’s case, TIRZ money would go toward the arena, while city officials plan to call a separate infrastructure bond next year — potentially on the ballot in May — to pay for the roads and sidewalks in the surrounding arena district.

“Traditionally, that is what the TIRZ would pay for,” said John W. Diamond, a tax and finance expert at the Baker Institute for Public Policy. “This is like the whole process on steroids … to develop an area with TIRZ money and then turn around and take out a bond to have the city then pay for the infrastructure.”

Because the TIRZ is overseen by a board whose members are appointed by city leaders, it also allows the city to direct large sums of money without seeking permission from voters.

“If you’re using a TIRZ, that is public dollars. It’s a mechanism which essentially absorbs funds that otherwise would go to the city’s general fund, and we know that’s the fund that services things like public safety, streets, sidewalks, drainage,” Councilwoman Teri Castillo (D5), on an Aug. 12 episode of ENside Politics.

What else the Spurs are offering:

The city will own the arena and lease it to the Spurs for an initial rent of $4 million per year, rising 2% each year after.

That money will also be used to help the city repay its arena bonds, as will the revenue the city makes from leasing new property around the arena district to private developers.

The deal helps keeps the team from leaving San Antonio for another city, requiring the Spurs to continue to play home games here for the next 30 years.

The team will also put $2.5 million per year, up to $75 million, toward a

community benefit agreement that the city can spend how it sees fit.

Compared to other teams in similar-sized media markets, Spurs owner Peter J. Holt said covering half of the arena’s cost was almost unheard of — on top of all of the other investments the team is making.

“This commitment shows our belief in the city the county and having a fruitful partnership that benefits all,” Holt said at an Aug. 5 commissioners court meeting.

After the City Council agreed to a non-binding “term sheet” with the Spurs weeks later, some critics have turned their attention toward the community benefit agreement and making sure that money is spent on education, transportation and other needs.

What happens next

City and county leaders agree the entire project will need reconsideration if voters don’t approve the county money in November.

If the venue tax increase succeeds, the team must deliver a large portion of its development promises before bonds are issued to build the stadium.

Several council members also want to see the independent economic analysis before that happens, and Jones would like city voters to approve their portion of the funding on a separate ballot. It’s unclear whether she’ll have colleagues’ support.

“There is an opportunity for City Council to put this to a public vote via simple ordinance,” Jones said after the Aug. 21 council meeting. “At the very least we should do it in this instance, given what a momentous and public investment this would be.”

Jasper Kenzo Sundeen contributed to this story.