As far back as the 1970s, operators conjured plans to move natural gas from Alaska’s North Slope to international markets, just as the fledgling global LNG trade was picking up.

Asian markets are tantalizingly close to Alaska’s southern coast, but projected costs and logistical difficulties sunk all attempts to connect.

Then President Donald Trump made Alaska LNG a focal point in his ongoing campaign against trade deficits.

In March, Glenfarne Group took over development of the Alaska LNG facility after it had spent the better part of the previous decade as a project for a quasi-state agency. Plans for the facility have been cut into phases that developers hope are easier to manage, and international customers are showing interest.

North Slope operators, such as Pantheon Resources, are working on supply deals to make the project affordable.

The project still draws doubts from analysts. Development costs are high, and it’s difficult to gauge just how sincere potential customers are when the U.S. president is exerting pressure.

“We had this moment of clarity, when we started having discussions, that we could do something that could cut through the Gordian knot of this 60 years of inability to get the project off the ground.”

“We had this moment of clarity, when we started having discussions, that we could do something that could cut through the Gordian knot of this 60 years of inability to get the project off the ground.”

—David Hobbs, CEO, Pantheon Resources. (Source: Pantheon Resources)

Developers, however, believe the current industry and political push will move things forward.

“We had this moment of clarity, when we started having discussions, that we could do something that could cut through the Gordian knot of this 60 years of inability to get the project off the ground,” said David Hobbs, Pantheon CEO.

Big and rough country

The North Slope, like the Permian Basin, is an oil-focused play, meaning the associated gas from production is incidental to the economic goals of most operators.

Unlike the Permian, Alaskan producers don’t have the option of sending gas to an LNG liquefaction terminal via an extensive pipeline network from one side of the state to the other.

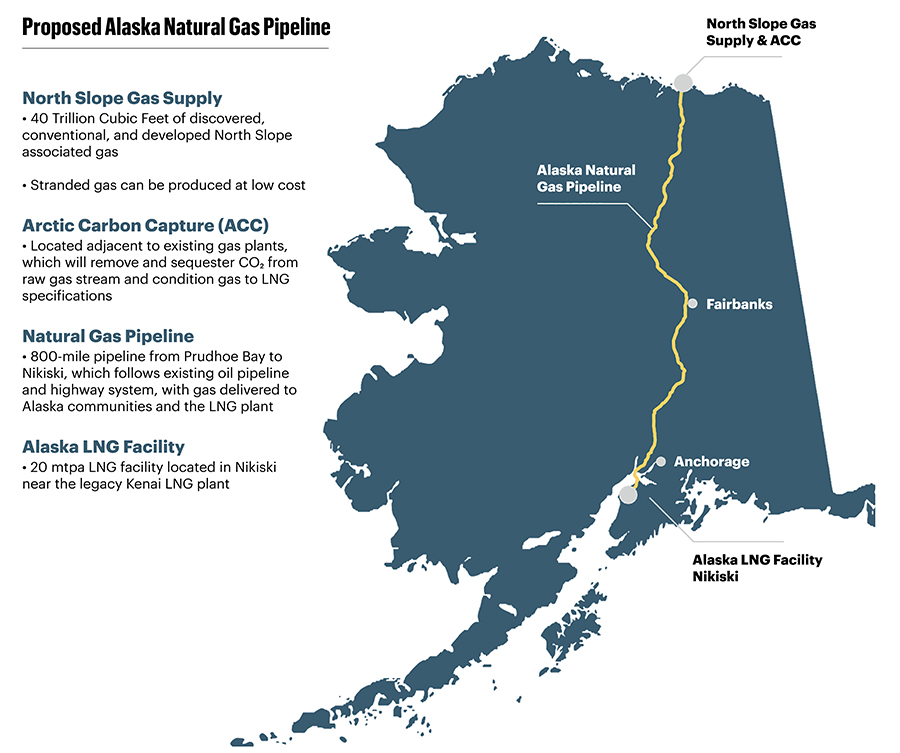

The Alaska LNG project aims to change that. Its proposed 42-inch, 807-mile pipeline is described as the backbone of the enterprise and would be built through some of the most hostile terrain on earth. (For comparison, the proposed DeLa Express Pipeline, which would deliver gas from the Permian to Louisiana, is 645 miles long.) The line would have a capacity of 3.3 Bcf/d of natural gas. The route would include two aerial crossings over rivers and above-ground crossings over active fault lines.

Producers will also likely need a processing plant at the source at a cost of an estimated $10 billion. Much of the gas produced on the North Slope is sour, and its CO₂ content is high enough that it can’t be shipped without causing corrosion concerns.

The total cost for the project is expected to be between $38 billion and $44 billion.

All of which reinforce some analysts’ doubts.

“The overall figure that we’re looking at in terms of capital expenditure is about $44 billion at the moment, and when you divide that by its capacity of 20 million tons of LNG per year, you get about $2,200 per ton,” said Sam Reynolds, research lead for gas and LNG at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “That is roughly double what the capital costs are for projects in the Gulf Coast.”

“This project is not going to get built during the Trump administration. Construction timelines alone, on average, for these kinds of projects take five years. This project hasn’t even begun construction, and it’s in really difficult terrain.”

“This project is not going to get built during the Trump administration. Construction timelines alone, on average, for these kinds of projects take five years. This project hasn’t even begun construction, and it’s in really difficult terrain.”

—Sam Reynolds, research lead, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. (Source: Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis)

Reynolds said he believes the primary motivation for customers has so far been political. It’s in the interest of trade negotiators to commit to a deal without necessarily signing the final contract, essentially playing a waiting game, he said.

“This project is not going to get built during the Trump administration,” Reynolds said. “Construction timelines alone, on average, for these kinds of projects take five years. This project hasn’t even begun construction, and it’s in really difficult terrain.”

Glenfarne has argued that the analysts are missing some of the fundamental economics that benefit the project.

“Glenfarne’s acquisition of Alaska LNG has catalyzed a wave of serious commercial interest in the project driven by fundamentals, not politics,” Glenfarne spokesman Micah Hirschfield said in a report by Natural Gas Intelligence in June.

Alaska LNG’s location provides logistical savings thanks to its nearness to Asian markets.

An LNG tanker trip from the Gulf Coast can take months to reach Asia. A trip from Alaska takes weeks. The difference will add up to billions in savings, Hirchsfield said.

The project has garnered agreements from several Asian customers. Thailand signed a 20-year agreement to procure 2 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) of Alaska LNG production. The project currently has half of its production reserved through agreements.

Gas suppliers have worked to make the project economically feasible on their end. Hobbs said the project’s development phases will make the cost easier to handle.

Phase 1 includes construction of the pipeline. The startup traffic of delivering natural gas to Southern Alaska will help finance the project. Hobbs said that Pantheon has offered natural gas at $1/MMBtu for the Alaska market’s use of the pipeline, allowing more money to be earned through tariffs.

Phase 2 would consist of the LNG plant and treatment facilities.

Glenfarne has also countered arguments that the costs of building a project in Alaska would be similar to building pipelines or LNG facilities in Canada. The projects in Canada were completed under a different regulatory regime.

The project is also working with industry veterans who have either developed LNG projects or worked in Alaskan terrain before. About $1 billion in prep work has already been completed, Hirschfield said.

Alaska as a state also has more experience with LNG than most competing nations.

Kenai LNG

ConocoPhillips’ Kenai LNG facility (right foreground) operated from 1969 to 2015 with Japan as its sole customer. Glenfarne’s Alaska LNG project would return the state to the market. (Source: Getty Images)

ConocoPhillips’ Kenai LNG facility (right foreground) operated from 1969 to 2015 with Japan as its sole customer. Glenfarne’s Alaska LNG project would return the state to the market. (Source: Getty Images)

ConocoPhillips built and opened the Kenai LNG Facility in 1969, with Japan as its sole customer. The plant was the world’s largest when it was built, with a capacity of 1.63 mtpa.

The plant operated for more than 40 years and shipped its last tanker load in 2015, when the local gas supply dried up.

ConocoPhillips tried to restart the plant the next year but could not find a baseload of customers to support the project, and far larger and cheaper LNG production took off along the U.S. Gulf Coast.

In 2017, the plant was mothballed and eventually sold to Marathon, but production at the site may not be finished. In January 2025, Harvest Midstream took ownership of the facility from Marathon with the intention of converting Kenai into an import terminal that will be operational by the end of 2026.

On the surface, the plan appears illogical. Why would a state on the verge of investing billions on an LNG exporting project want to import LNG?

Supporters, however, contend the projects serve two different purposes.

The Kenai import terminal will solve the immediate problem of a declining natural gas supply in south-central Alaska, said Bruce Jackman, vice president of Marathon’s Kenai Refinery, according to a May report in Alaska Business.

The Alaska LNG project is designed to deliver North Slope natural gas to the international market, serving as a profit-maker for the oil companies in the north. Glenfarne plans to reach a final investment decision on the project by the end of the year.

Hobbs said that producers and the state are developing the facility in a way that would finally work for customers and producers.

“Everything I hear says that that everyone is moving as constructively as possible forward to realize this project for themselves and for the state of Alaska,” he said.

Proposed Alaska Natural Gas Pipeline Map. (Source: Alaska Gasoline Development Corp.)

Proposed Alaska Natural Gas Pipeline Map. (Source: Alaska Gasoline Development Corp.)