“Had the real operational story been known — the handicaps imposed by weather, the fact that scouting missions were flown on no more than one day in four, the uncertainty of navigation — it may be wondered if the Americans would have undertaken what in the end proved to be a losing endeavor.” — Douglas Robinson, “Up Ship!”

Germany’s use of the terrifying, bomb-dropping zeppelins slipped over England’s unprotected cities in little-known aerial battles of the Great War. And the United States was keeping tabs.

From 1921 to 1935, the Navy maneuvered five lighter-than-air flying giants — alas, to a catastrophic end, spare one.

The U.S. Bureau of Aeronautics had selected San Diego as the site of the West Coast terminus for transcontinental airship flight. Airships occasionally called on our growing metropolis, landing at Kearny Field (now Marine Corps Air Station Miramar) and North Island’s budding air station.

ZR-2

As early as 1919, Great Britain’s R38 had been contracted as a training vessel for U.S. designers and airmen. Rigid airships were supported by internal framework, as opposed to being shaped by their lifting gas, as were the smaller blimps. We wanted the technology.

In 1921, R38’s silver hull was walked from its shed at Bedford, England, only to reveal various mechanical snags during trials.

These were corrected, engineers had hoped. But never mind, America’s not-yet-designated ZR-2 (zeppelin rigid) R38 broke apart in a fiery crash into the Humber River in Hull, England. All but five of the 49 on board lost their lives in the hydrogen hell. Interestingly, one of the airmen is buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in Point Loma.

A striking monument at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in Point Loma honors Charles Ivan Aller, who was killed in the R38/ZR-2 crash in Hull, England, in 1921. (Karen Scanlon)

A striking monument at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in Point Loma honors Charles Ivan Aller, who was killed in the R38/ZR-2 crash in Hull, England, in 1921. (Karen Scanlon)

ZR-1

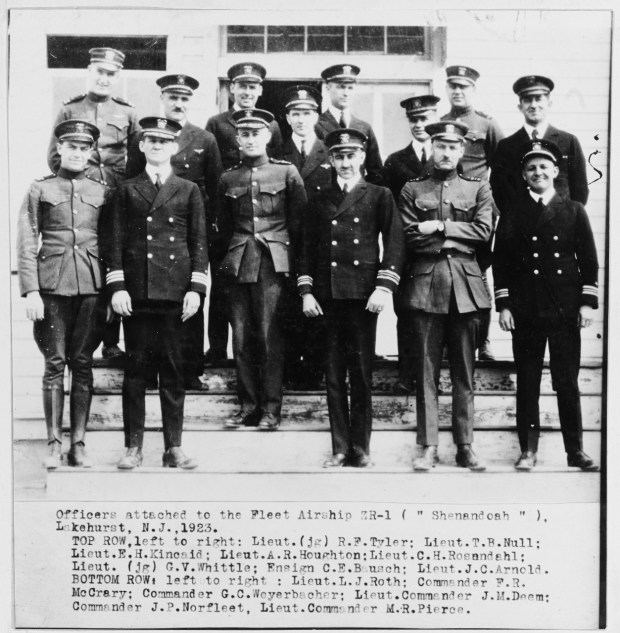

Back in the States, ZR-1 was in trials for airworthiness out of the new Lakehurst Naval Air Station, N.J. The 680-foot USS Shenandoah’s maiden flight in September 1923 marked the first use of non-flammable helium, the first rigid flown by an American crew and the first to depart Lakehurst.

Interestingly, ZR-1’s first commanding officer, Frank McCrary, served a brilliant naval career and resided in Coronado between duty stations and until his death in 1952.

Shenandoah’s first crew was led by Commanding Officer Frank McCrary (front row, second from left). (Provided by Mary Ann McCrary Thomas)

Shenandoah’s first crew was led by Commanding Officer Frank McCrary (front row, second from left). (Provided by Mary Ann McCrary Thomas)

Adm. William Moffett, an ambitious proponent of the Navy’s airship program, with Commanding Officer Zachary Lansdowne piloted the ship to San Diego via Texas in October 1924. Upon arrival at North Island, an ill-prepared mooring crew let the rear gondola hit the ground, bending a vertical girder.

Repairs were made within a week and Shenandoah rose over San Diego Bay to join its battle fleet in military exercises off San Pedro. It returned to North Island, filled its “tanks” and turn-tailed home.

On Sept. 2, 1925, Shenandoah lifted away from Lakehurst under Navy orders and against Lansdowne’s experienced judgment. The ship headed west into a threatening sky — and to its demise the following day.

“Flashes of lightening lit the morning horizon. Shenandoah’s five Packard engines struggled and she slipped sideways over the hilly Ohio landscape. A powerful air current that thrust her upward at too great a speed — conditions no airship was designed to endure — captured the struggling sky giant,” noted the authors of “Hindenburg: An Illustrated History.”

The ship continued to rise and fall until it split in two. The control gondola let go first, taking Lansdowne with it. The stern section, carrying 22 crew members, rose again to 2,000 feet, then leveled and floated to earth a half-mile from where the ship snapped.

Members of the public and Navy personnel visit the USS Shenandoah’s crash site in Noble County, Ohio, on Sept. 3, 1925. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Members of the public and Navy personnel visit the USS Shenandoah’s crash site in Noble County, Ohio, on Sept. 3, 1925. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Fourteen of Shenandoah’s 45 airmen died that day, a number far fewer than the fate that would meet its sister ships.

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of Shenandoah’s final flight, the Noble County Historical Society, military historians and Navy personnel met Aug. 31 at its national monument in Ava, Ohio. Signs displayed in the rural area mark the three sites where Shenandoah last touched the earth.

ZR-3

German airship engineer Hugo Eckener, manager of Luftschiffbau Zeppelin Co., was behind the push to sell the new LZ 126 to the U.S. in a gesture of war reparation.

In October 1923, the silver hull emerged one last time from its shed in Friedrichshafen, following months of trials, making a last zeppelin flight over the German fatherland.

After crossing the Atlantic, LZ 126 was christened USS Los Angeles (ZR-3) in November 1924 and maintained a superb flying record.

There were mishaps, of course, including a wind gust that lifted the stern straight up while moored at high mast, airmen grasping for anything they could.

The ship was decommissioned, put back into service and then took a final bow at Lakehurst in 1939 before being dismantled.

ZRS- 4

There are no images of the 785-foot airship USS Akron plunging into the stormy Atlantic in April 1933 — only later photos of wreckage being taken to the surface.

On board was an impressive collection of officers of the Bureau of Aeronautics out for a demonstration flight along the East Coast. Akron’s fin hit the waves and plummeted beneath the surface, taking 73 souls, including Adm. Moffett. Three crewmen survived.

During Akron’s two-year active duty, calamities occurred, including an attempt to land at San Diego’s Camp Kearny. The hot sun expanded helium, increasing the ship’s lift. It suddenly rose with mooring cables dangling. Three men gripped a cable, but two fell to their deaths. The third clung feet to a wooden toggle until he could be pulled to safety.

ZRS-5

The zeppelin rigid scouts Los Angeles and Macon were constructed at the Goodyear-Zeppelin Airdock in Akron, Ohio, and carried “trapezes” for launching and retrieving single-engine Sparrowhawks. They were aircraft carriers.

Macon, christened in March 1933, was transferred to Naval Air Station Sunnyvale (later renamed Moffett Field), where it would participate in naval maneuvers off Northern California. Commanding Officer Herbert Wiley was one of the three survivors of the Akron crash.

The USS Macon is moored at Naval Air Station Sunnyvale in the Bay Area in the 1930s. (Moffett Field Museum)

The USS Macon is moored at Naval Air Station Sunnyvale in the Bay Area in the 1930s. (Moffett Field Museum)

In February 1935, Big Sur lighthouse keeper Thomas Henderson reported seeing “the top fin or stabilizer go all to pieces. The ship began to lose altitude.” In fact, the upper fin punctured three gas cells, and efforts to keep the ship buoyant failed.

Macon yielded to the sea, and nearby vessels of the Pacific Fleet plucked all 83 airmen from the water. One man lost his life when he jumped ship too soon.

The submerged wreck of the USS Macon remains within the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, where the colors of one of the airship’s Sparrowhawk biplanes are still visible 90 years later. (NOAA-MBNMS)

The submerged wreck of the USS Macon remains within the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, where the colors of one of the airship’s Sparrowhawk biplanes are still visible 90 years later. (NOAA-MBNMS)

Were airships a good idea?

Lives, material and dreams were lost when Macon went down, thus ending the trials and successes of naval airships. Yet we might applaud the dreamers and builders of the large rigids for their bold ingenuity.

Karen Scanlon is a historian, a freelance writer and a volunteer at Cabrillo National Monument in Point Loma.