By Trevor Fairbrother

The Queer Lens project made me think about queer culture and camera culture as distinct phenomena that began in the Victorian era: each was a manifestation of modernity.

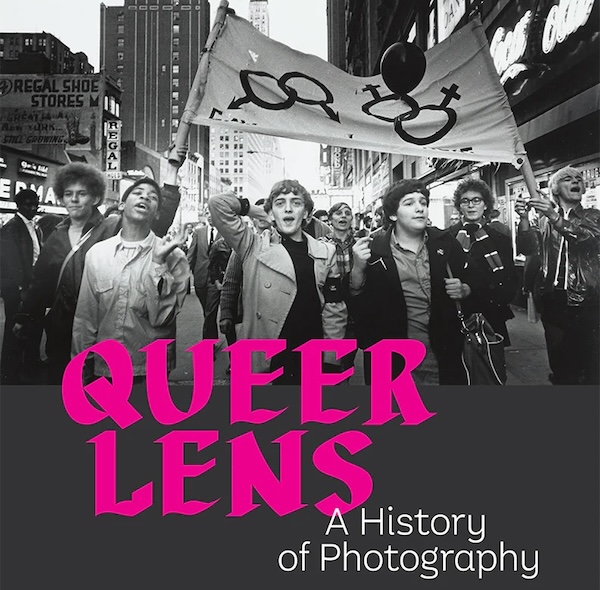

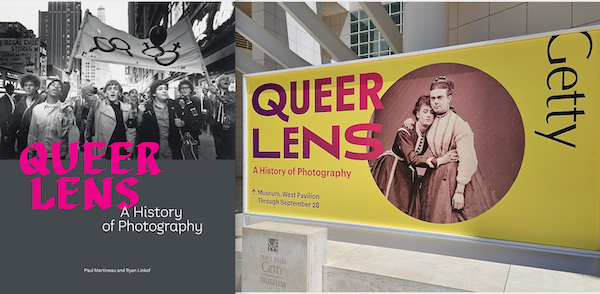

Left: the cover of Queer Lens featuring “Gay Liberation March on Times Square” (1969) by Diana Davies. Right: placard for Queer Lens outside the Getty Museum, with a detail of Frederick Park and Ernest Boulton aka Fanny and Stella (ca. 1870) by Frederick Spalding. Photo pairing by author.

The latest exhibition that Paul Martineau has curated at the J. Paul Getty Museum is titled Queer Lens: A History of Photography and features more than 270 works by 157 artists. The show is accompanied by an impressive hardcover catalogue of the same name (Getty Publications, 342 pages, $65), co-edited by Martineau and Ryan Linkof. An extensive introduction and a richly illustrated chronology—both co-written by the editors—open the book, followed by five essays: two by artists (Ken Gonzales-Day, Catherine Opie), three by scholars (Jordan Bear, Alexis Bard Johnson, Derek Conrad Murray). It has 207 plates of photographs included in the exhibition, and they are organized into the following chronological sections.

1839-1900

Invented in 1839, the photographic enterprise evolved rapidly. By the 1850s, the glass plate negative made it possible to generate multiple prints on paper. Amateur photography and camera clubs flourished in the 1880s. With the launch of the first mass-marketed camera, the Brownie, in 1900, photography reached a broad public. Even though many early photographs were suppressed or destroyed during outbursts of homophobia, those that exist are evidence of queer lives. For instance, the catalogue illustrates a hand-colored daguerreotype from around 1848 showing a tender moment between two reclining naked women—likely produced in France for the international underground market in erotic imagery. It also includes Frederick Spalding’s portrait of two cross-dressing actors who performed in the late 1860s as stylish ladies named Fanny and Stella..

1901-1945

In his 1900 study of “sexual inversion,” Havelock Ellis concluded that homosexuality was usually present at birth and advised against attempting to “cure” it. Pictures in this section range from “vernacular” to “fine art” photographs. Some are informal records of same-sex friendships and social occasions, others are portraits of splendid self-involved careerists, including Bessie Smith, Marlene Dietrich, and Cecil Beaton. The most avant-garde works depict Claude Cahun and Marcel Duchamp as stylish, intelligent nonconformists. There are indications of the permissiveness that prevailed briefly in nightclubs in the ’20s as well as glimpses of friendships formed between women serving in the armed forces and men in the priesthood.

Left: Unknown French maker, “Two Women Embracing,” (ca. 1848), hand-colored daguerreotype, J. Paul Getty Museum. Right: JEB, “Priscilla and Regina, Brooklyn, New York,” 1979; image from JEB’s book Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians, courtesy Anthology Editions. Photo pairing by author.

1946-1980

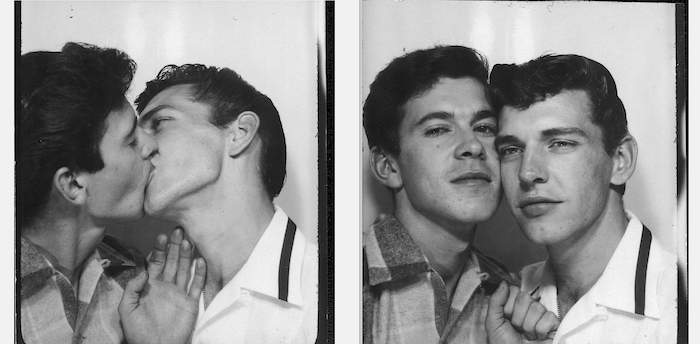

This period saw an increase in LGBTQ+ visibility, inspired in part by the fight against the American Psychiatric Association’s listing of homosexuality as a mental illness. In 1947, Dr. Alfred Kinsey of the University of Indiana created a nonprofit institute devoted to “Sex Research.” He worked with photographer George Platt Lynes who created representations of a same-sex sensibility and exploits. There was also a proliferation of male physique magazines, which Queer Lens alludes to with works by Bruce of Los Angeles and the Western Photography Guild. While such publications were not overtly political, they cultivated networks of people attuned to a “gay gaze.” The book reproduces pictures of J.J. Belanger, a World War II veteran, hugging and kissing a friend in 1953: these men could not be intimate in public, but they memorialized their intimacy behind the curtain of a photo booth. Numerous plates in this section reflect the tumultuous era when civil rights activists, feminists and the burgeoning Gay Liberation movement crusaded for societal change. They include a photograph of joyful young people leading a march on Times Square, taken by Diana Davies in 1969, and a supremely tender portrait of a Black lesbian couple at rest in a park, taken by JEB [Joan E. Biren] in 1979.

1981-2020

In 1981, after the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documented the disease eventually named AIDS, the gay community was maltreated and stigmatized on an unprecedented scale. Some plates in the section touch on the fear, anger and resilience that this unleashed. In 1990 four members of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) went on to found the group Queer Nation, which fostered the move to reclaim the term “queer,” turning an old, cruel slur into a contemporary term that connotes inclusivity and respect. The plates in this section include searing conceptual pictures by David Wojnarowicz and gorgeous unflinching depictions of defiantly queer individuals by Catherine Opie. There are also visionary works by Texas Isaiah and Tourmaline, representatives of a new generation of artists who celebrate Black, trans, and queer voices.

The blurb on the book’s back cover declares: “Queer Lens: A History of Photography is the first major publication to survey the history of photography through a prism of queerness.” Today’s leading American art museums often stoop to this kind of self-promoting chatter, but, ironically, this particular boast is contradicted by Martineau and Linkof in their “Introduction.” They mention a recent publication by British art historians Flora Dunster and Theo Gordon – Photography: A Queer History (Ilex Press, 2024) – which is devoted to the same subject matter. Alas, the co-authors of the Getty’s catalogue cannot resist one-upmanship: “[Photography: A Queer History] includes a comprehensive look at queer photography in a visual sense, but its thematic structure, with short essays and artist biographies, precludes a deep dive into the material.” There is yet another insightful and copiously illustrated book on this topic: Calling the Shots: A Queer History of Photography, edited by Zorian Clayton (Victoria & Albert Museum, 2024). The British publications from 2024 did not accompany museum exhibitions. All told, these three queer/photo books are handsomely produced and they productively investigate the intersecting histories of photography and queer culture. I don’t care which one might deserve a medal for the deepest dive, but, for what it’s worth: only the V&A’s book fails to mention academic writers Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault; the two British books include Alvin Baltrop, a Black artist who recorded the pre-AIDS queer scene in lower Manhattan, but the Getty’s book does not; the Getty’s catalogue applauds commercial photographers David LaChapelle and Herb Ritts and the other books ignore them.

Photographs of J. J. Belanger and his friend in a photo booth in Hastings Park, Vancouver (ca, 1953); in the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries. Photo pairing by author.

As a double-barreled project – exhibition plus book – Queer Lens is “provocative and important, and the timing packs a wallop.” They are the words of renowned art critic, Christopher Knight, whose review for the Los Angeles Times stated, “Queer Lens is the provocative photography show only the Getty would be brave enough to stage.” This is Knight’s rundown of our repressive times: “[Queer Lens] opens during a state of national emergency. The ACLU is tracking 597 anti-LGBTQ+ bills in state legislatures across the U.S., including six in California. (Texas leads the hate-pack, with 88.) Most won’t pass. All, however, mean to intimidate just by being introduced. The show conjures an oppressive frame of social reference again and again.” In addition to welcoming the project’s political reverberations, the Los Angeles critic pointedly stressed the power of its visual nuances and insights in a forceful sentence: “Often it is subtle.”

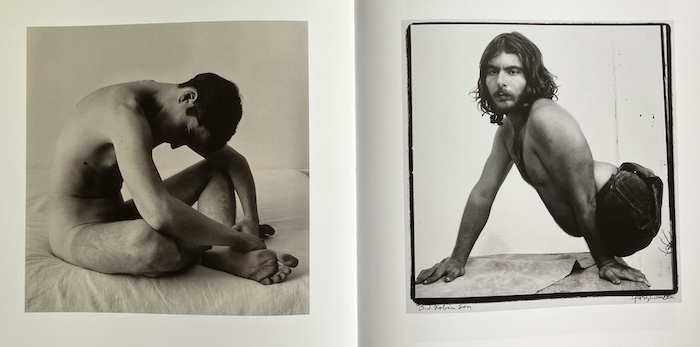

While I have not seen the exhibition, I can report that the layout of the book has some moments in which subtle poetic discernment matches activist ties. One spread juxtaposes Frances Benjamin Johnson’s Susan B. Anthony (ca. 1900-06) with Emil Otto Hoppé’s Henry Havelock Ellis (1922). An intensely emotive pairing shows Peter Hujar’s Paul Hudson with George Dureau’s B.J. Robinson, both pictures from 1979. The first shows a naked, introspective man sitting cross-legged on a bed, his head lowered and his face in shadow; the second portrays a beautiful, dignified, muscular double amputee, who is balancing on his hands. This inspired pairing goes unexplained: there is no textual information about the artists or their sitters. At first, the educator in me objected to this refusal to illuminate, but I decided that this kind of bracing and uninhibited staging is one of the strengths of Queer Lens. The book, after all, is devoted to the goal of queer self-expression and the long history of suppression and repression that haunted open defiance of the norms of gender and sexuality. The Hujar/Dureau spread reminded me of the words Queer Nation chanted when combating gay bashing in New York City in the 1990s: “We’re here! We’re queer! Get used to it!”

A spread from the book Queer Lens: Peter Hujar, “Paul Hudson” (1979) and George Dureau, “B.J. Robinson” (1979). Photograph by author.

The Queer Lens project made me think about queer culture and camera culture as distinct phenomena that began in the Victorian era: each was a manifestation of modernity. Photographs quickly became vital tools for marginalized voices. The Getty’s website rightly asserts: “The immediacy and accessibility of the medium has played a transformative role in the gradual proliferation of homosocial, homoerotic, and homosexual imagery.” That said, it is also significant that the histories of photography and queer culture were so fervid and disputatious. Such words as invert, homosexual, gay, and queer have meant different things in different eras. Because photography seems to straddle art and science, there has been uncertainty about its status and purpose. New York’s Museum of Modern Art appointed its first curator of photographs in 1940; the Getty Museum followed suit in 1984; the Metropolitan Museum of Art did not establish a self-contained Department of Photographs until 1992.

Martineau and Linkof are to be commended for a narrative that extends into the present. For example, their book touches on new trends in photography, including the use of AI to construct imagined portraits, and it speaks up for young trans artists who work in defiance of social censure and legal punishment. They salute photographers of every generation, and write, “This volume is part of the ongoing project of recovery and recognition of the achievements of people whose stories are often untold.”

Trevor Fairbrother wrote an essay for Donald Platt’s book of poems Tender Voyeur, published last month by Grid Books.