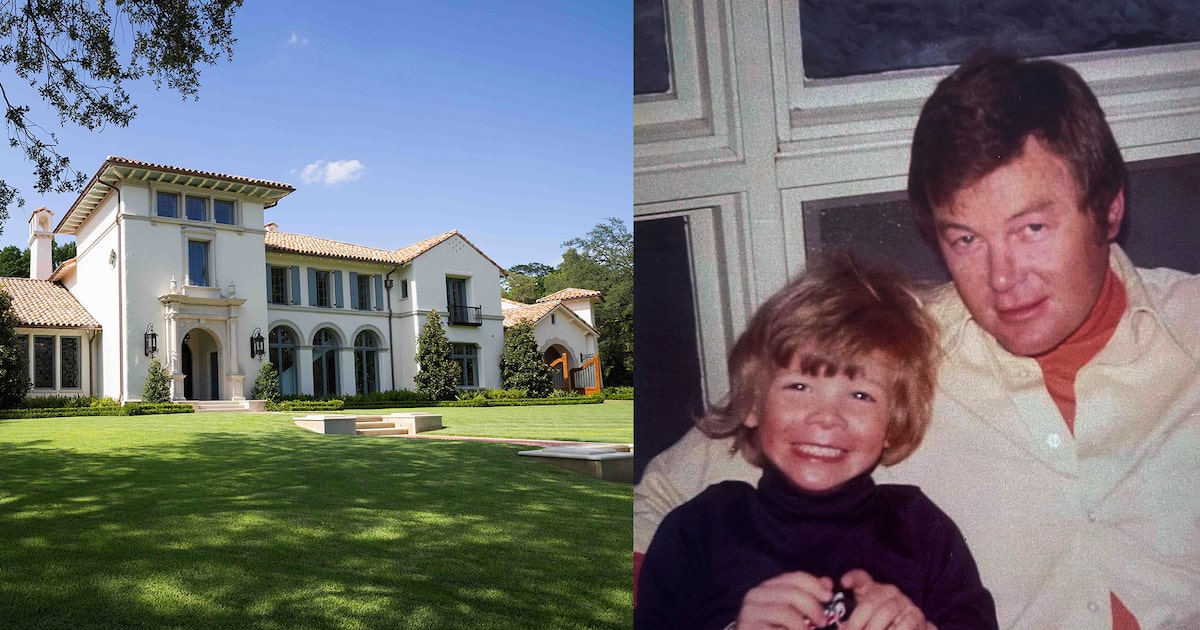

The $34.5 million mansion would look at home in Beverly Hills or West Palm Beach — the Spanish Revival style, with its hand-troweled stucco and red barrel tile — but in the blackland prairie of North Texas, it really only belongs in Highland Park, the OG neighborhood of affluence. A few blocks away, on Preston Road, you can spot Harlan Crow’s estate at the end of a private drive and farther down the road is Jerry Jones’ mansion, not that you can see it from the street.

4400 Belfort Place is comparatively open, its roughly 14,000 square feet rising at the corner of Armstrong Parkway, a thoroughfare known for towering oaks strung with lights at Christmastime. Highland Park is a place rooted in tradition: country clubs, debutante balls, old-money cliques. It’s hard to belong in a place like this; I should know, I tried it once. So did Blair Pogue, the developer behind this newly constructed mansion, which The Wall Street Journal wrote up earlier this year as “one of the priciest homes in Texas.”

The Dallas Morning News also wrote about 4400 Belfort Place, and I tapped open the story at the top of the most-read list only to stumble upon a familiar name. Blair Pogue is the third son of Mack Pogue, the late Dallas real estate mogul who ran Lincoln Property Co., but for much of my life, I knew Blair as my brother’s best friend from high school.

A rich kid who never acted rich, Blair was about as nice as an older sibling’s running buddy could be, much nicer to me than my brother, who was in a real “ignore your sister” phase. (We’re friends now.) I was surprised to find Blair making such a flashy move, though, not only because I remember him at 18, banging out to AC/DC and Black Sabbath, but also because I understood him to have stepped away from his father’s empire. He’s now 55, and for the past decade, Facebook told the story of a man deeply involved in nonprofit work with orphanages in Russia and the Ukraine. Real estate — the family business — was not his bag.

News Roundups

“You only learn in life through your failures,” he told me. “And man, I’ve learned a lot.”

One lesson I learned growing up middle-class in Highland Park was that the shiny palaces of my classmates never told the full tale. The prettiest houses could contain the ugliest stories, the wealthiest kids had some of the poorest childhoods. Not Blair, whose childhood was pretty charmed. But all families are complicated, no matter their income. A façade of a home is only, after all, a façade.

If you look closer, the $34.5 million mansion on Belfort Place tells the story of growing up in a great man’s shadow, the gift and burden of inheritance and the unexpected path of building a legacy.

It’s the story of one man finding his way.

Blair Pogue, the third son of legendary real estate guru Mac Pogue, inside the grand estate he recently developed at 4400 Belfort Place in Highland Park. The author can confirm he was not interested in fashion as a teenager, either.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

The ‘Succession’ of the family Pogue

I met Blair at Cafe Pacific, the power-lunch spot that anchors Highland Park Village. He hasn’t changed much since high school: ruddy cheeks, an easy laugh. But maturity had given him a way of straight-shooting about his past that made my job as an interviewer quite easy.

“I worked for my father from 1992 to 1997, and I could not get my feet under me,” he said. “I’m watching all these buildings getting built, so much getting done. I just wasn’t getting a lot done.”

I was curious what Blair thought of Succession, the great HBO show about the mixed bargain of wealth. The three siblings at the heart of the series traipse through homes straight out of Architectural Digest, but their psyches are nightmares of insecurity, overcompensation, a desperate need for validation. Whether that warp is about privilege or the dynamics of a specific family is an open question, but one takeaway from Succession might be that it’s much easier, or at least more fun, to build an empire than to inherit one.

“I hate to put this on record,” said Blair with a chuckle, “but the patriarch of Succession sometimes reminds me of my father.”

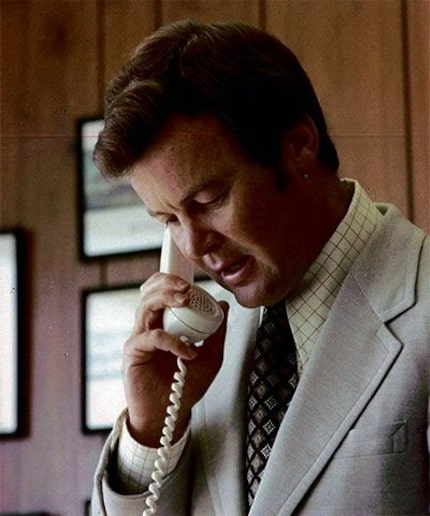

Mack Pogue founded Lincoln Property Co. and grew it to one of the country’s largest real estate operations.

Contributed / Lincoln Property Co,.

Mack Pogue lacked the abrasiveness of Logan Roy, the Rupert Murdoch stand-in who presides over Succession’s media conglomerate. But the similarities are hard to deny: the Scotch-Irish heritage, the business they built themselves, the ability to command any room. Let’s agree that real estate moguls don’t become that way by deferring to everyone else.

Mack was born middle-class in Sulphur Springs, son of a cotton gin owner, but he moved to Dallas with his wife, his high school sweetheart Jean, and took a job at a real estate firm.

This was the early ’60s, and the Dallas skyline was being redefined by Trammell Crow, a self-made scrapper who’d become a real estate king. Mack started showing up at his office. “I want to work for you,” he told Crow, who was probably a bit taken aback by this. “You’re the best.” Eventually Crow relented; this kid was tenacious. Crow had been contemplating a move into apartments, and so he offered the young Pogue a trial run. A fruitful partnership and lifelong friendship was born.

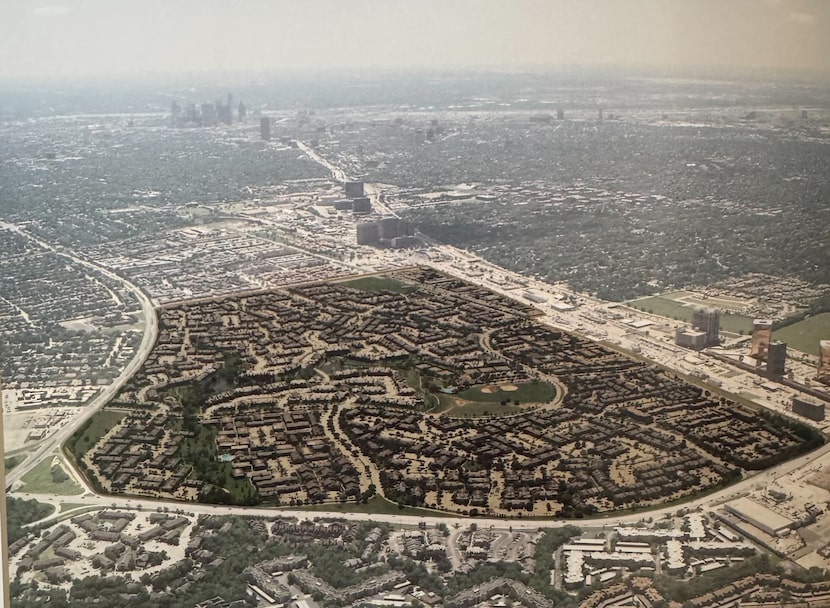

Early aerial shot of the Village Apartments near Lovers Lane and Greenville Avenue.

courtesy Blair Pogue

“The first thing I try to look for is a nice person,” Crow told D Magazine in 1984. “Next is brains.” Mack had both in spades.

In 1965, Mack and Trammell joined forces to create Lincoln Property, named for the 16th president. In 1968, the Village Apartments opened near Lovers Lane and Greenville Avenue, an adults-only complex that became a pad for swinging singles in a part of the state teeming with young adventurers from Mineola and Sweetwater and Mineral Wells. The place still had its party reputation in the early ’80s, when a kid named Mark Cuban holed up with five guys in a three-bedroom complex where keggers were a standard entertainment fixture.

Lincoln Property kept expanding: Ross Tower, Lincoln Centre. By the ’70s, Mack had branched out on his own. “Tell Trammell that I’m going to keep chasing him,” Mack once told D Magazine, a line that captures the duo’s playful rivalry. “That’s going to keep him young.” Lincoln Property eventually built more than 200,000 apartments nationwide.

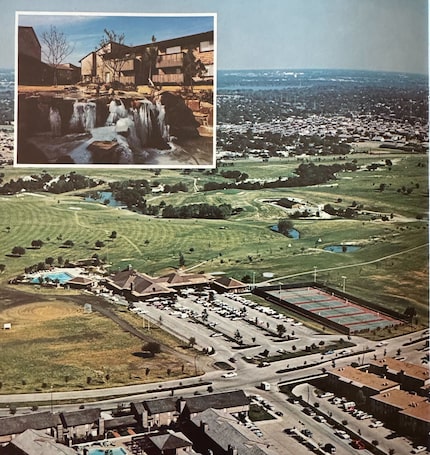

Growing up with the Village

The Village Country Club (inset) in the late ’60s. Check out that traffic.

courtesy Blair Pogue

Mack had three sons, and each came of age working at the Village. “Dad was like, you’re gonna be in real estate. You need to know it from the ground floor,” Blair says.

Blair spent his summers working with service techs on apartment turns and sweeping up near the 30-odd pools, a task that sounds more daunting when you consider how many cigarette butts must have been lying around. Blair loved it, though. I’m sure the sight of all those bathing beauties didn’t hurt.

School was a different story. He played on the Highland Park football team, but he struggled in class. He wonders now if he should have gone to Shelton, a private school for learning differences that his oldest daughter attended. But this was the ’80s, and people weren’t so sophisticated about cognitive challenges like dyslexia, so Blair leaned on my brother. Josh was a National Merit Scholar who’s never shied away from flexing what he knows (trust a younger sister).

Blair Pogue, right, with his high school friend Josh Hepola, who happens to be the author’s brother. Apparently there are no photos of them from high school, because: guys.

courtesy Josh Hepola

Blair graduated in 1988, the same year the government banned adults-only complexes, and the Village began its next phase as a slightly less party-centric but still-vital compound for young professionals.

Blair’s next phase took place close to home, at Southern Methodist University. His brother Blake, eight years older, was already thriving in dad’s real estate world, starting his own company, Phoenix Property, in 1994. His middle brother Brent had the unusual obsession of coin collecting, though he was very good at it.

“He actually put together the most exclusive American collection that has ever been assembled,” Blair told me. Blair’s not exaggerating: Known as the D. Brent Pogue Collection, it contains 600-plus silver and copper rarities dating back to the late 18th century. There are books about it.

“Growing up in that family and trying to do real estate, it was impossible,” Blair says. “I hesitate to use the word compete,” he begins, searching for a word less barbed with sibling rivalry, but he doesn’t find one, probably because the word he’s looking for is compete.

Blair Pogue, left, with his wife, Cristin, at a party at 4400 Belfort Place.

courtesy Douglas Newby

If the Succession comparison holds — and really, it’s only a loose blueprint — then Blair would be Roman Roy, the wisecracker played by Kieran Culkin. Blair is much sweeter, not nearly such a cynical loudmouth, but what I recognize in both of them is a deference to the family, a softness born of being last. The baby.

The past several years have brought an online discourse about “nepo babies,” kids born into success by virtue of their parents’ accomplishments. What the cultural resentment rarely takes into account is how challenging it can be to grow up inside someone else’s legacy. Your success might never feel like something you earned, even as you eclipse your parents. (See: Gwyneth Paltrow.)

Or, like Blair, you might feel a bit lost for a long time.

‘I think it killed him’

Blair and his dad started investing together, more of a father-son bonding experience than an actual job, but it gave Blair other opportunities. He became involved with orphanages in Russia, the Ukraine, India and Latvia, first from a capital improvement standpoint and later, when it became clear that wasn’t enough, from a human development angle. He traveled a lot.

He got married and had three kids, but he and his wife eventually split, and he married Cristin Cox, another Highland Park grad. They live in a Forest Hills home with a garden where Blair loves to lose time.

Blair Pogue, center, visiting an orphanage he works with in India in 2024.

Courtesy Amy Norton

Facebook is an unreliable narrator, but several years ago, I started sensing something amiss in the family Pogue. Indeed, Blair’s middle brother Brent died in 2019. His coin collection had been a massive accomplishment, but once it was complete, and he sold the coins, what was left?

“I think it killed him,” Blair says. “Once he finished that, he’d done it. And unfortunately, he was addicted to alcohol, and he self-medicated.”

Blair cleaned up his own act after his brother died; his drinking had dipped into the danger zone. COVID hit, and his father was diagnosed with dementia, a slow descent that understandably worried the family. Mack decided to sell Lincoln Property, though it would be more accurate to say he spun off its parts. Blair did not inherit any of them. He knew that wasn’t his path — but what was?

Charlie Brown, Lucy and the football

Blair went to his father, as he often did in moments of personal crisis, to talk about possible careers. Mack had an idea. He’d been holding on to the family estate on Bordeaux Avenue, even though he and Jean had moved to another home nearby. Once a Tudor in all its splendor, the Bordeaux house had become a fire hazard, but Mack couldn’t part with it. Maybe his third son could help.

“Why don’t we build a spec house and sell it to somebody we know will take care of it?” Mack proposed to Blair, who spent the next 18 months assembling an ace team, designing a new house, overseeing the basement build. This was fun!

Then one day Blair got a call from his dad’s business partner. “Hear y’all sold the Bordeaux lot,” the guy said. Blair was confused. He wasn’t aware of any sale. But another partner of his dad’s was moving back to Dallas, and Mack had sold him the lot, a detail he failed to mention to the son who’d spent a year and a half masterminding a house to build there.

“I love my father, but he was very Lucy and the football,” Blair says, referring to the Peanuts comic strip. “He would tee me up, and I’d come running in. He’d pull the football up, and there’s Charlie Brown, missing the ball, every time.”

Mack did feel guilty about this, so he suggested pairing up on another spec home. Blair found the perfect spot — a rare one-acre lot in Highland Park — but this time his mother yanked the football. One day she called to inform Blair she could not let her fading husband enter a big real estate venture, not with his diminished capacity. Blair couldn’t say no to Mom.

Maybe next time, Charlie Brown.

The family Pogue: Mack Pogue, center, with his family at Christmas in late 2023, about a month before he passed away.

courtesy Blair Pogue

Mack passed away in 2024 at 89, the end of an era in Dallas real estate. Only after his death was an extravagant gift announced: $100 million left to UT Southwestern and Children’s Health. Mack was never one to tout his generosity.

By that point, Blair was at work on a new era in his own life. He’d bought that one-acre lot in Highland Park, bringing in his children, now in various stages of college and high school, as 50-50 partners. He named his company Blantyre, a Tudor-style estate in the Berkshires that Blair loves.

“It all worked out,” he says, with the peace of a man who has discovered the rough patches of life can be a door to a new adventure.

It is an irony not lost on him that only after his father died could he make his own power move.

The $34.5 million estate at 4400 Belfort Place feels surprisingly homey, with a stained-glass hallway that leads to a zebra-wood library.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

Inside a $34.5 million mansion

4400 Belfort Place is one of 37 one-acre lots in Highland Park. Most recently, it belonged to a man who bought it for $6 million so his kids could attend HP, but they’d graduated. He listed the property as a lot with an asking price around $9 million, which would be a nifty take-home for him and a number that struck Blair as vastly under-market. A perfect real estate transaction: Everyone wins.

“A home with this level of artisanship hasn’t been built in a generation,” says broker Douglas Newby, as he takes me inside the property. Most new homes these days are modern or close to it: those huge windows, the minimalist museum look. The mansion on Belfort is different; it seems grand and intimate at once.

Blair enlisted Newby, the well-connected agent behind Architecturally Significant Homes, as part of his dream team. Newby arrived looking dressed for a Gatsby garden party in a linen jacket with a pale blue pocket square. Tall with a charming spray of salt-and-pepper hair, he bears a striking resemblance to conservative firebrand Steve Bannon.

“It really is kind of ridiculous,” Newby says with a sigh.

Hanging with the boys, from left: Blair Pogue, broker Douglas Newby and real estate attorney John Reoch at a party for 4400 Belfort Place.

courtesy Douglas Newby

Newby tours me around the home, which I hadn’t expected to like so much. The stained glass of the first-floor hallway, which leads to the zebra wood of library bookshelves. I’m enchanted by a pattern wood-beam ceiling in the living room that looks like a white maze, Moroccan in style and very geometrically soothing.

“Blair hasn’t pounded his chest, but the house would not be this successful if he didn’t have a vision,” says Newby, pointing out nuanced details, like an eight-pointed star pattern, carried throughout each room.

Of course part of that vision was assembling the right people. The landscape architect is Harold Leidner, whose many high-profile projects include the Preston Hollow estate of former state senator John Carona. The architect is Larry Boerder, who worked on the $50 million Preston Road villa of John and Lyn Muse, while the interior designer is Margaret Chambers, whose mix of classical styles has transformed spaces in North Texas, the Hill Country and beyond.

The bold dining room of 4400 Belfort Place features glossy lacquer walls and gold starbursts on the ceiling. Margaret Chambers was the home’s interior designer.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

The light dusty blue of the interior reminds me of places I’ve visited in Montauk. Calming ocean waves. The dining room is entirely original: glossy lacquer walls, gold starbursts on the ceiling, a boldly specific look for a spec home, though Newby prefers to call it “bespoke.” Two side-by-side refrigerators in the kitchen look more like cabinets. Apparently the richer you are, the more you can disguise household appliances. I had mistaken an elevator in the entryway for a closet.

I’m not a fan of ginormous houses, but I’m surprised to find the place feels homey. All the warm wood, wrought-iron fixtures, Venetian glass. I’d dipped into the comments section of The Wall Street Journal article enough to know 4400 Belfort was not to everyone’s taste. “This kitchen makes me dizzy,” wrote one disgruntled reader. Another simply said, “Gross.” As one astute commenter put it, “The WSJ Mansion comments section: where multimillion-dollar houses get torn to shreds.”

The downside of building a home with such specificity is that some folks won’t like it. The upside is that others will, a lot. “Where’s my checkbook?” wrote one commenter, and I was in that camp.

‘A Great Guy Makes Good’

Blair arrives to join us in a suit that’s too big. He’s lost weight recently, but I can’t help remembering the teenager with a disinterest in fashion. As he poses near the winding staircase for a photo, he fidgets, uncomfortable in center frame.

To be rich is to never have to apologize, but to be born rich is to always be apologizing. Do you deserve this money? What does that even mean? As impressed as I am with Blair’s family, he is always quick to shift the conversation to my own: the onetime intellectual weirdos of Highland Park, with their Great Books and advanced degrees. I grew up embarrassed by my childhood home, a too-small rental house on a busy street, but that was not Blair’s observation about us. I take his compliments as genuine affection, but also a distaste for talking about himself. His father was like this, too: Beware the spotlight.

We head upstairs to the second floor, whose two bedrooms are Blair’s favorite features. In each room, a delicate stained-glass quatrefoil roughly resembles a four-leaf clover. When light streams through the glass, the reflection on the ground is almost like magic.

Landscape architect Harold Leidner designed the stately and serene backyard of 4400 Belfort Place.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

We head to a balcony overlooking the pale turquoise pool, and from this vantage point, the place feels like a resort. A cabana with a kitchen and bath, the generous terrace, the eight-point stars and crosses etched in the lawn, a highly manicured look that is something of a Harold Leidner trademark. But the tour is not done yet: We head back downstairs and into the basement, where a modest gym sits to the side of what could be a private club. There is a wet bar and a wine cellar with a ribbed barrel ceiling. An expanse of Mediterranean tile is just dying for the world’s best poker night.

I ask Douglas, who knew Mack Pogue, about the similarities between father and son. Blair looks sheepish, as this is probably his worst nightmare: being compared to Dad, on the record. Douglas sits on the stairs, threading his fingers through his floppy hair. “Mack is a really nice guy,” he begins.

“But I’m nicer,” says Blair, and everyone laughs. It’s true. One of Blair’s challenges in an operation of this magnitude has been learning to say no. Blair is a people-pleaser by nature, but yes-manning leads to disaster with so many creatives looking for guidance. He’s no longer the baby who must defer to his father and siblings, though. He’s his own man.

A wine cellar in the basement of 4400 Belfort Place has a ribbed ceiling, one of many Moroccan touches.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

Later Douglas emails me, having chewed on this question further. “The Village Apartments are the only apartment development I know that got better every year for 50 years,” he writes. “Home builders are always looking for ways to cut corners, but Blair as a home developer was always looking to improve the home during the process. Both of them were always quietly striving to create the best,” he writes, referring to father and son.

In the moment, though, Douglas has another way to spin the tale. “If I were going to headline this story,” he says, “I’d call it, A Great Guy Makes Good.”

Blair always had it in him. He might have spent much of his life trying to prove that — to his family, to the onlookers of social media, to strangers at a restaurant — but the person he really had to convince was himself.

‘I always wanted to make my mark’

The $34.5 million mansion has gotten interest, but a place of its scale could take a year to sell. Blair isn’t worried. His father taught him success was in the ingredients: the right lot, the right team. The rest takes care of itself. Blair is already looking for another project, but he won’t buy anything until this one sells.

After visiting 4400 Belfort Place, I kept reflecting on what it means to build a home. Dallas is so overrun with real estate developers I’ve been a bit dismissive of the work and attention that doing it properly requires. It’s no easy feat to construct a home that fits in a neighborhood of such heritage. I found myself wishing Mack were alive to see this. I wasn’t the only one.

“I always wanted to make my mark,” Blair told me at lunch. “I feel like I finally made that mark, but my father is not here. It’s a little painful, I’m not gonna lie. It hurts.”

But the idea of an inheritance, apart from money and its complications, is that the people who made us live on inside us. We all have an inheritance, whether we like it or not: the smile that was our father’s, the genes and personality quirks that find a new home inside a child.

And so, Mack Pogue lives on — in the apartments he built, in the generous ways he gave to Dallas. Most of all, in the sons who carry on his legacy, one example of which is for sale at 4400 Belfort Place, a $34.5 million mansion whose future owners, at least from my perspective, should consider themselves lucky.

Designer on the rise: Dallas native wins top prize at prestigious London fashion show

Designer on the rise: Dallas native wins top prize at prestigious London fashion show

Now bound for a job at Dior in Paris, the recent college grad eschews traditional silhouettes in their work.

Hepola: ‘MasterChef’ Tiffany Derry’s success proves how restaurants — and Dallas — changed

Hepola: ‘MasterChef’ Tiffany Derry’s success proves how restaurants — and Dallas — changed

North Texas’ celebrity chef built a suburban empire on duck-fat fried chicken and old-fashioned kindness. “No one will talk crazy to anyone in my kitchen.”