SACRAMENTO — Mikey Vaughn stacked his three passports on a table as he waited to testify before state lawmakers about immigrants’ access to health care and the effects of Trump administration policies. The hues of each one retraced Vaughn’s journey: dark red for Colombia, blue for the U.S. and black for New Zealand.

“I know how important a document can be for our undocumented community,” said Vaughn, who was adopted from Colombia and later lived in New Zealand before returning to the U.S. “For me, having this document has been a privilege. For others, not having this has made their lives hell in this country.”

Vaughn is a certified nursing assistant at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He’s one of many health care workers around the country fighting to help immigrants safely obtain care amid actions to cut coverage and give immigration agents access to medical facilities.

“When patients don’t trust that their health care spaces are safe, they end up suffering in silence,” Vaughn told lawmakers later that day, “and put their health, their family’s health and our communities at risk.”

Mikey Vaughn, center, speaks during a hearing of the California Assembly’s Committee on Health on June 24, 2025, in Sacramento. Vaughn, a certified nursing assistant in Los Angeles, is flanked by Mar Velez, left, of the Latino Coalition for a Healthy California and state Sen. Jesse Arreguín. (Photo by Aaron Stigile/News21)

Mikey Vaughn, center, speaks during a hearing of the California Assembly’s Committee on Health on June 24, 2025, in Sacramento. Vaughn, a certified nursing assistant in Los Angeles, is flanked by Mar Velez, left, of the Latino Coalition for a Healthy California and state Sen. Jesse Arreguín. (Photo by Aaron Stigile/News21)

The assault on immigrant health care is coming from different fronts — at both the federal and state level, and even in blue states such as California.

In January, the Trump administration rescinded Biden-era guidelines that prohibited immigration agents from detaining people at protected areas such as schools and churches — but also medical facilities, such as hospitals, doctors’ offices, community health centers and urgent care clinics.

So-called “sensitive location” policies date to the early 1990s. But the Trump directive eliminates specific guidelines and instead allows immigration authorities to use their own discretion about enforcement in such places.

In a statement about the new policy, the Department of Homeland Security said the administration “will not tie the hands of our brave law enforcement.”

Since the change, reports of agents entering medical facilities have drawn criticism and protests.

In July, activists rallied outside Glendale Memorial Hospital, a Dignity Health facility just north of Los Angeles, after immigration agents were allowed to remain in the lobby while a woman they wanted to apprehend received treatment.

In a statement, Dignity Health said it shares “a desire to keep our neighbors safe” but added that the hospital cannot legally restrict law enforcement from public spaces.

Also in July, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents entered a surgical center in Ontario, California, to detain a Honduran landscaper. Two health care workers who tried to intercede have since been charged with assault and conspiring to prevent a federal officer from discharging his duties.

A niece of worker José De Jesús Ortega said on a GoFundMe page that her uncle “showed bravery in the face of injustice, and now he’s being punished for it.”

This spring, Aditya Harsono, a supply chain manager at Avera Marshall Regional Medical Center in Marshall, Minnesota, experienced the sensitive location changes directly.

His lawyer, Sarah Gad, said Harsono got an email from the hospital’s vice president, asking him to meet in the basement regarding his job. When they got there, immigration authorities were waiting.

“There’s two ICE agents in plain clothes who handcuff him and won’t tell him where they’re taking him, and they just said, ‘You’ll find out later,’ ” Gad told News21. “It was like, effectively, he’s been kidnapped.”

Harsono, who is Indonesian, is married to a U.S. citizen and had a green card application pending at the time of his arrest, Gad said. He was in the country under a student visa that was revoked when the administration began targeting international students.

Harsono is now out on bond and awaiting finalization of his green card, his attorney said. Officials with Avera Medical Center did not respond to requests for comment.

The change in sensitive area guidelines doesn’t mean law officers can access any part of a facility, according to Jenny Horne, an attorney with the Legal Aid Society of San Mateo County. Spaces labeled “private” can be entered only with a judicial warrant, she said.

Andrew Cohen, an attorney with Boston-based Health Law Advocates, noted that facilities can establish private spaces by using signage or putting patient areas behind locked doors.

Nancy Hagans, an immigrant from Haiti and president of National Nurses United, called the reversal of the sensitive location policy “a disaster and a shame” and said health workers fear patients will not seek vital care.

A protester holds a sign advocating for immigrant patients at a “No Kings” protest in Los Angeles on June 14, 2025. Under the second Trump administration, attacks on immigrant health care are coming from different fronts at both the federal and state level, and even in blue states such as California. (Photo by Sydney Lovan/News21)

A protester holds a sign advocating for immigrant patients at a “No Kings” protest in Los Angeles on June 14, 2025. Under the second Trump administration, attacks on immigrant health care are coming from different fronts at both the federal and state level, and even in blue states such as California. (Photo by Sydney Lovan/News21)

She pointed to one patient who in March needed a lifesaving blood thinner medication. “We don’t know if she was afraid to come in to pick up, so we went and dropped the medication to her,” said Hagans, who works at Maimonides Medical Center in New York City.

“I need to be able to get up every day and do my job and save patients’ lives, regardless of their immigration status,” she added. “Our job is to do no harm.”

Research confirms that people in the country illegally are worried about obtaining health care under the second Trump administration. Even immigrants with legal status are avoiding care, according to health policy organization KFF. In a May survey, 1 in 10 lawfully present immigrants said they or a family member had avoided seeking care since President Donald Trump took office.

On an early June afternoon outside a health clinic in San Jose, Rafael, a 54-year-old from El Salvador, acknowledged how hesitant he was to go for in-person care. In April, he was assaulted during a robbery; he still has trouble speaking because of his injuries. He asked that his full name not be disclosed, out of fear for his safety.

“I was working in maintenance for some apartments and did what I could, but today I’m not doing well. I can’t work, and I can’t help with anything,” he said, adding that these days, he rarely leaves the house over worries he could be detained.

“I am scared to sit outside,” he said.

Amid the administration’s actions, health care advocates and unions are working to educate patients and workers alike. They also are pushing lawmakers for added protections.

At Hagans’ hospital in New York, employees have protocols about what to do if ICE shows up: Take a badge number, and call a 24-hour number for assistance.

“Our job is not to say, ‘Patient so-and-so is in such room,’ ” Hagans said.

In New York, her union has distributed know-your-rights pamphlets in community centers, churches and food banks. The pamphlets encourage patients to carry valid immigration documents to appointments and remind them of their right to remain silent.

In California, nurses at Chinese Hospital in San Francisco have picketed for patient safety, and the California Hospital Association published guidance about how hospitals should handle patient privacy and enforcement activity.

In Colorado, a recently signed law expands protections for immigrants at public medical facilities. Policies restrict the release of certain data, prevent agents from entering nonpublic spaces without a warrant and prohibit arrests of noncriminal immigrants while they are in court-ordered behavioral health treatment.

“I really just don’t think that a clinic is the place to be doing this,” said Dr. Apoorva Ram, an internal medicine physician in Aurora, Colorado, who co-authored an op-ed in support of the legislation.

Some states, however, are taking the opposite stance. In Ohio, a bill pending in the Legislature would require hospitals to give immigration agents access — or lose certain funding. And a bill in Arizona would have required some hospitals to record their patients’ immigration status, but it was vetoed by the state’s Democratic governor.

‘A chilling message’

In California, Vaughn serves as co-chair of the immigration work group for SEIU-United Healthcare Workers West, a union representing more than 120,000 people.

He passes out know-your-rights cards at medical facilities and rallies. He’s helped facilitate a webinar to educate the public about the immigration system and what to do during interactions with agents.

And in June, he flew from Los Angeles to Sacramento to testify before the California Assembly’s Committee on Health about a bill similar to the one passed in Colorado.

California recently passed a budget that cuts and restricts Medi-Cal for immigrants. (Photo by Alissa Gary/News21)

California recently passed a budget that cuts and restricts Medi-Cal for immigrants. (Photo by Alissa Gary/News21)

The measure would reclassify a patient’s immigration status as medical information and ensure it couldn’t be disclosed without a judicial warrant. It also would require health workers to notify higher-ups if immigration agents requested access to a facility, a patient or provider documents.

“The recent presence of immigration agents at hospitals and clinics sends a chilling message that even in a medical emergency, patients and workers alike are at risk for being targeted and deported,” Vaughn told the committee.

Like so many others fighting for immigrants’ access to care, Vaughn is driven by his own background.

He was an infant when his parents brought him to the U.S. from Colombia, and he remained a green card holder until adulthood. At 14, he recalled, he was separated from his mother at the Los Angeles airport when returning from overseas. His visa was one digit off from the number on his Colombian passport, he said, and officers had questions.

Even today, he said, he remembers “the callousness, the coldness, the alienating nature of it all.”

While Vaughn said he would know what to do if immigration agents show up at his workplace, he’s not sure others would.

Mikey Vaughn holds up his “blue badge buddy” on June 24, 2025, in Sacramento. The clip-on badges provide advice about what to do if immigration agents show up at a health facility. (Photo by Alissa Gary/News21)

Mikey Vaughn holds up his “blue badge buddy” on June 24, 2025, in Sacramento. The clip-on badges provide advice about what to do if immigration agents show up at a health facility. (Photo by Alissa Gary/News21)

“From my observations and my conversations with my co-workers, I do not believe people are ready for an ICE raid that would be looking to take our patients, let alone even themselves,” he said.

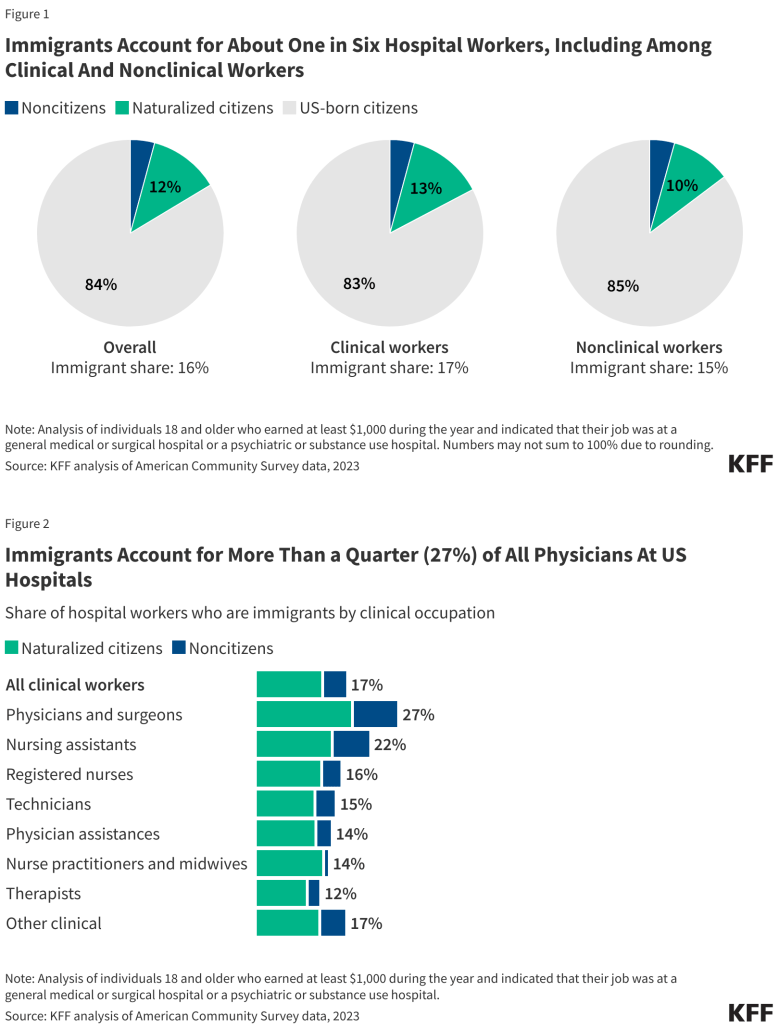

Immigrants make up a growing portion of health care workers in the U.S., studies show. According to the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University, the percentage of health workers who are immigrants increased from 14.2% to 16.5% from 2007 to 2021. The total number of health care workers in the U.S. grew by 4 million in that time.

“We have nurses from India, the Philippines, Asia, Africa,” said Sandy Reding, president of the California Nurses Association. “We have nurses from all over the world coming to help us, and we need them.”

A KFF analysis shows that at U.S. hospitals, immigrants account for about 1 in 6 clinical and nonclinical workers and more than a quarter of doctors.

Seema Kanani is one of those immigrant health care workers. She was 11 when her family immigrated to the U.S. from India, and she remembers wishing that she could just blend in.

“As I became an adult, that feeling kind of became my guiding light,” she said. “No one should ever feel that way.”

She is now a medical social worker for elderly patients at a clinic in Milpitas and an organizer with SEIU-United Healthcare Workers West, helping to pass out know-your-rights cards and ensure that hospital administrators safeguard the rights of immigrant patients.

Kanani recalled how she had to advocate for her father when he was in the hospital a few years ago. “That was it for me,” she said. “I realized I’m in this work for my passion, because I truly do believe health care is a human right, and why do people have to worry and struggle for a basic right?”

The sensitive location change isn’t the only action affecting immigrant health care under the second Trump administration.

After reporting by the Associated Press, the attorneys general of 20 states sued the administration for turning over Medicaid recipients’ personal information to the Department of Homeland Security for immigration enforcement purposes.

An individual approaches the SEIU-United Healthcare Workers West office on June 30, 2025, in Oakland. The union is working to protect immigrant patients. (Photo by Alissa Gary/News21)

An individual approaches the SEIU-United Healthcare Workers West office on June 30, 2025, in Oakland. The union is working to protect immigrant patients. (Photo by Alissa Gary/News21)

In other moves, the massive tax and spending cut bill Trump signed on July 4 makes some lawfully present immigrants, including refugees and asylees, ineligible for traditional Medicaid and Medicare, as well as the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program.

It also slashes Medicaid by about $900 billion, analyses show, and is expected to increase the number of uninsured people in the country by about 10 million.

Community health centers, which provide care regardless of a patient’s insurance status or ability to pay, received 43% of their funding from Medicaid in 2023, according to a KFF analysis.

“The money you cut from Medicaid means that the hospital has less money coming in and the health center has less money coming in,” said Steve Weinman, a consultant who has been involved in the community health centers movement for decades.

“Basically, all these entities are going to be sitting here with a big hole in their budget, and they’re going to have to cut services,” he added.

At the state level, even Democratic strongholds such as Illinois and California have reduced or eliminated health programs for immigrants.

Citing budget constraints, Illinois on July 1 ended its Health Benefits for Immigrant Adults program, which provided care to immigrants ages 42-64 who had no legal status.

Only a year ago, California opened its public health insurance program, Medi-Cal, to all eligible residents, regardless of immigration status. But in June, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a budget that freezes new enrollment to anyone 19 or older who is in the state illegally. That freeze starts Jan. 1.

For many other unauthorized immigrants who already are enrolled in the program, dental benefits will end in 2026, and a new $30 monthly premium kicks in starting in 2027.

State leaders said the cuts were needed, in part, because of “faster than projected” growth of Medi-Cal and other costs affecting the state budget, including recovery from the Los Angeles wildfires.

Johanna Liu is president and CEO of the San Francisco Community Clinic Consortium, a partnership of 12 community health centers that Liu said serve around 110,000 patients annually.

Of concern to Liu is that the new budget ends a system that reimbursed these clinics at a higher rate to help cover the cost of caring for the uninsured and underserved.

“So, if clinics can’t get this rate, they’re the ones that have to make tough choices: Do I continue to see my patient, or do I not continue to see my patient because I can’t afford to?” she said.

Some doctors said providing health care to immigrants is more cost-effective than not doing so.

Dr. Annie Ro, a professor at UC Irvine cited the My Health LA program, which ran from 2014 to 2024 in Los Angeles County and connected uninsured patients — including immigrants — with care.

Ro, who researched the program’s effects, said patients did not require costly health care services, such as emergency room visits or hospitalizations, as frequently.

“When this population … has good and complete access to care, they can avoid some of these costly (emergency department) visits,” she said.

Armed U.S. Marines guard the back entrance to the Edward R. Roybal Federal Building, adjacent to a Veterans Affairs clinic, during a “No Kings” protest in downtown Los Angeles on June 14, 2025. (Photo by Sydney Lovan/News21)

Armed U.S. Marines guard the back entrance to the Edward R. Roybal Federal Building, adjacent to a Veterans Affairs clinic, during a “No Kings” protest in downtown Los Angeles on June 14, 2025. (Photo by Sydney Lovan/News21)

California has long been viewed as a sanctuary for immigrants. The state restricts law enforcement from assisting in federal immigration arrests. And when the Trump administration deployed several thousand troops to Los Angeles this summer to counter anti-ICE protests, Newsom and others pushed back.

But given the new restrictions at the state level, advocates are concerned.

Kanani questioned the idea of the Golden State as an immigrant sanctuary — which, she said, is a place where someone can speak out in public without fear of retaliation or harm.

“The minute Marines and National Guard were present in our streets, it stopped being a sanctuary state,” she said. “The minute we separated undocumented folks from basic rights, it’s no longer sanctuary.”

As for the state’s cuts to immigrant health care: “Now we have set a model for, ‘Oh, well, if California can do this, then we can do this,’ ” she said. “If our line in the sand is here, other states may put their line way more conservative, and then what?”

News21 reporter Alissa Gary contributed to this story. This report is part of “Upheaval Across America,” an examination of immigration enforcement under the second Trump administration produced by Carnegie-Knight News21. For more stories, visit https://upheaval.news21.com/.