For the first time since 2008, Houston Ballet has mounted a production of John Cranko’s Onegin. After seeing the show, the only real question is, why so long?

The ballet opens with the young country girl Tatiana, nose in a book and thoroughly uninterested in the preparations for her upcoming birthday festivities. As more girls gather, they decide to play a game, where supposedly one sees their future love in a mirror. While peering into the mirror, Tatiana catches a glimpse of Onegin, a friend of Olga’s fiancé Lensky, who is visiting from St. Petersburg. Tatiana is immediately enamored with this stranger, but Onegin shows little interest in her or anything else. Undeterred, Tatiana pens a love letter to Onegin that night and dreams of them together.

Unfortunately for Tatiana, the letter has the opposite of its desired effect; the letter only annoys Onegin, who cruelly rips it up at her birthday party. Making things worse, Onegin turns his attention to Olga, flirting with her and stealing her away, repeatedly, to dance – none of which escapes Lensky’s increasingly offended eye.

Honor insulted and pushed too far, Lensky challenges Onegin to a duel that leaves Lensky dead and Onegin horrified. It’s years before Onegin sees Tatiana again, and when he does, it’s in St. Petersburg, where Tatiana is now married to a prince. This time, however, Onegin is a little older, a little grayer, and very much in love with Tatiana.

Though certainly not the first adaptation of Alexander Pushkin’s 19th-century poem-novel, Eugene Onegin, Cranko’s 1965 ballet has proved to be one for the ages. It’s emotionally moving, resonant, and incredibly accessible. Though the show has a clear emphasis on acting and storytelling, Cranko devised some passages of dance and pas de deux that are not to be missed. The acting though…

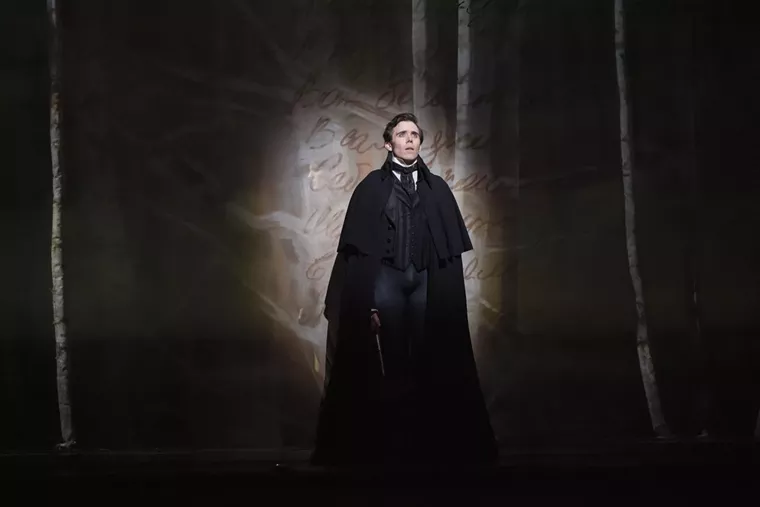

Houston Ballet Principal Connor Walsh as Onegin in John Cranko’s Onegin.

Photo by Alana Campbell (2025). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

Houston Ballet is made of not only world-class dancers, but acting powerhouses, which is crucial to a ballet that requires a lot of character work, like Onegin. As usual, the company shines in works like these, and Onegin is no different. (It’s worth noting that aside from our main characters, there are also many funny little character moments throughout the group scenes to entertain you, like Kellen Hornbuckle’s angry pout across the stage or Riley McMurray’s partner indecision.) Across the board, the ensemble impresses, particularly during the first act.

There’s the fanciful play of the women’s group and the high-jumping, knee-dropping men, whose choreography is flavored with bits that harken back to Russian folk dance and simply fun to watch. And, of course, there’s a frolicking, rollicking group dance toward the end of the first scene of Act I, which culminates in the coupled-up ensemble crossing the stage, this way and then that, the women in leaping jetés with support from their partners. It’s as exciting a display as one can see and well deserving of the enthusiastic round of applause it elicited.

As the titular character, Connor Walsh strikes quite the imposing figure. Onegin appears dressed in all black, back ramrod straight and nose turned up, the expression on his face that of a man in the midst of an existential crisis and not panicked by it, but resigned. But though the show bears his character’s name, make no mistake about it: This ballet is all about Tatiana, a role beautifully played by Karina González.

As Tatiana, González brilliantly captures both the girlish longing in Tatiana’s youth – exhibited with heartbreaking clarity during her Act II solo, her eyes repeatedly straying to Onegin, begging for his attention and visibly disheartened when it’s not received – and the harder-earned maturity of her adulthood. She takes the first step toward that maturity at the close of the second act, the tables turned as she is now the one standing up straight and looking at Onegin head-on, rose-colored glasses off, as he falls apart following his duel with Lensky.

Houston Ballet Principals Karina González as Tatiana and Connor Walsh as Onegin in John Cranko’s Onegin.

Photo by Alana Campbell (2025). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

González’s success at playing the naïve country girl is apparent in Act III, when Tatiana and Onegin meet again, though this time he is the one begging for her affections. Desperation spills from Walsh, contorting his face and coloring every sweep and pass across the stage as Onegin tests Tatiana’s resolve. At one point, he literally holds her back as she takes giant, trudging steps forward only to fall back into his arms after each. It’s a far cry from Tatiana and Onegin’s slight and distracted (on Onegin’s part) partnering earlier, though reminiscent, and even further from the mirror pas de deux, where the two come together with equal passion to a frenzied score.

(Famously, for reasons, Cranko was unable to use the music Tchaikovsky composed for the operatic adaptation, so instead Kurt-Heinz Stolze culled works from Tchaikovsky’s oeuvre, all of which were masterfully played by Houston Ballet Orchestra under Conductor Simon Thew.)

The mirror pas de deux is almost aggressively physical, with Walsh lifting, sliding, carrying, catching, and spinning González all around the stage. It’s dramatic and exciting, especially in moments such as when González dives into his arms or when Walsh lifts her high and straight above his head. Considering Tatiana’s dream at the start, the moment when she finally banishes Onegin from her life for good hits especially hard. On González’s crumpled face and trembling body, it’s clear Tatiana still loves him and rejects him at a cost, but it’s all the meaningful for it.

Houston Ballet Soloist Sayako Toku as Olga and Principal Angelo Greco as Lensky with Artists of Houston Ballet in John Cranko’s Onegin.

Photo by Alana Campbell (2025). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

Sayako Toku danced the role of Tatiana’s sister, Olga, with a spring in every step. As Olga, Toku is so light one thinks she may float away. That head-in-the-clouds quality might help explain why she couldn’t see how dismissing her fiancé might be big trouble later. But before things go wrong, Toku dances a sweet, exuberant pas de deux with Angelo Greco’s Lensky. Greco also has a moody, thoughtful solo as he mentally prepares for the duel, an unexpected but lovely emotional beat for the audience.

Finally, Syvert Lorenz Garcia played Prince Gremin, who is mostly ignored by the Onegin-obsessed Tatiana before returning in Act III as her husband. Together they dance a rather stately pas de deux which, though devoid of passion, is not without connection or affection. It’s a line he and González traversed well.

It would be a crime not to mention how easy on the eyes this production is. Santo Loquasto’s sets and costumes are gorgeous, from the country dresses and gold-toned garden and pavilion, with its flower-adorned chandeliers, in the first two acts, to the opulence of the blood-red ballroom and Tatiana’s matching dress in the third. The stick-thin trees that populate the garden return in a much more sinister fashion in the second act, the moodiness enhanced by James F. Ingalls’s often dramatic lighting choices.

As far as season-openers go, it’s hard to imagine Houston Ballet choosing a better one. Cranko’s show is a classic, and the production is flawless. So, what else do you need to know?