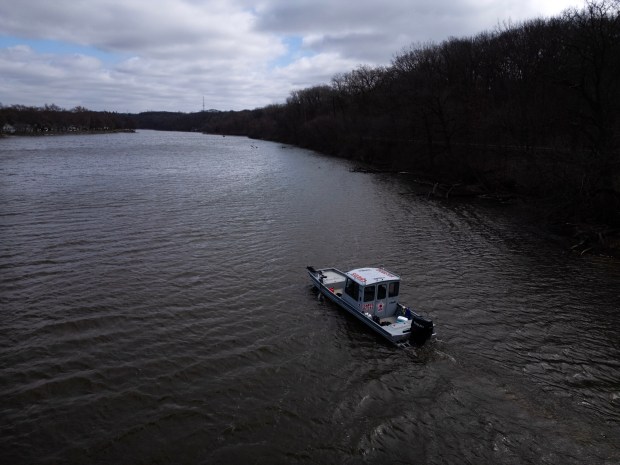

Darick Langos toppled backward into the Chicago River and came up grinning. He tapped his head twice and splashed a little water into his scuba mask. Then he called out to the crew still aboard the boat bobbing in the water just south of the Cermak Road bridge.

“Love you! Bye,” he yelled.

With a whoosh, he sank down to the riverbed to peer through the murky green. But instead of collecting samples of water or aquatic life, Langos was searching for license plates and brand emblems from “a pile of cars” on the river floor.

The self-described Chaos Divers have been boating up and down the Chicago River for much of the week, canvassing for evidence to help crack a handful of long-cold missing persons cases.

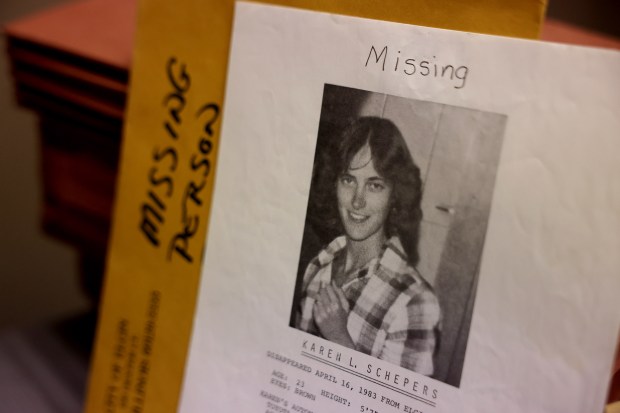

The group, which shares its exploits on social media, has been crisscrossing the country since late June to dive lakes and rivers where they believe people and their cars may be at the bottom. Earlier this year, they helped identify and retrieve from the Fox River a Toyota Celica belonging to Karen Schepers, which had been missing — along with Schepers herself — since 1983. The group, running largely off of YouTube subscriber revenue and donations, said it’s found 20 people over about four years of diving, including five Illinoisans.

Thursday afternoon, Langos resurfaced from his first 20-foot dive after about eight minutes, holding a rusted steering wheel over his head. He clambered back onto the 26-foot powerboat and added it to a stack of rusted, bent license plates taken from nearly 100 cars the group has located at the bottom of the river.

Maverick, the group’s gray Labradoodle, scurried back through the boat’s cockpit. Langos gave a quick rundown of what he’d seen: a 1996 Ford Explorer, “all the windows busted out, nobody inside of it, on its wheels.”

The fact that the car was upright was of some note, the group’s general manager Lindsay Bussick said.

“Most vehicles that we find are upside down,” Bussick said. “And so the car will go in the water, the air in the tires will flip it upside down, and the weight of the engine will pull it down.”

The Explorer was one of what Bussick, 41, described as “quite a large pile” just south of Ping Tom Memorial Park. Over the week, they have found Fords, Chevys, SUVs, sedans and pickup trucks — “just about anything you could kind of find in a car lot” as they canvassed the river, she said.

Chaos Divers dog Maverick watches as Jacob Grubbs, owner of Chaos Divers, swims in the Chicago River near Cermak Road, Sept. 4, 2025. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Chaos Divers dog Maverick watches as Jacob Grubbs, owner of Chaos Divers, swims in the Chicago River near Cermak Road, Sept. 4, 2025. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

But the diving group’s owner Jacob Grubbs said many of the vehicles were so deteriorated that they were essentially piles of metal and frames.

“Whatever these are, they’re so dilapidated there’s no describing ‘em,” he said, yanking his diving hood off to free a bushy gray beard.

Grubbs, 42 and a resident of Harrisburg in southern Illinois, said he used to work as a coal miner and enjoyed sharing his adventures as a white water kayaker on YouTube. He became a scuba diver in November 2019, he said, and started to get involved with other scuba search and recovery teams such as Adventures With Purpose, which recovered the remains of Nathan Ashby in December 2019.

Grubbs, Lindsay Bussick and her husband Eric — first working from a kayak and later from a series of donated or sponsor-provided boats — found their first missing person in October 2021, when they helped locate the body of Charles Fluharty in Liverpool, Ohio. They’ve been working steadily since, they said, taking multiple trips every year as far away as Canada and as close by as East Moline. By the time they started to explore the Chicago River, they’d been on the road in an RV for more than two months.

Show Caption

1 of 28

Detective Andrew Houghton, third from right, watches the Toyota Celica of Karen Schepers being loaded onto a flatbed truck after being taken out of the Fox River on March 25, 2025, in Elgin. (Stacey Wescott/Chicago Tribune)

Sometimes local law enforcement agencies will ask the divers for help on a specific case, as Elgin police did when they were searching for Karen Schepers. Or family members of missing people will commission the group for help finding their loved ones. But the group also does its own tracking for missing people and makes its best guesses for where people and their vehicles might be, in hopes of being able to forward a fresh lead to local law enforcement.

Edward and Stephania Andrews, both 62, of Arlington Heights, circa 1970. (Chicago Tribune archive)

Edward and Stephania Andrews, both 62, of Arlington Heights, circa 1970. (Chicago Tribune archive)

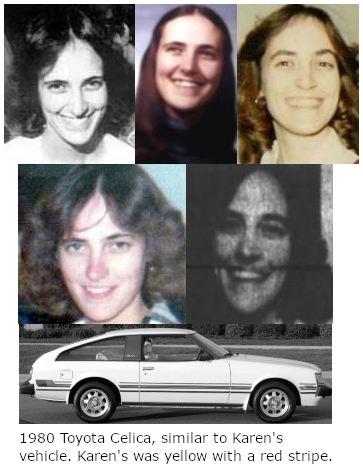

That’s what they’d done for the white whale for the Chicago arm of the trip, a 1969 yellow Oldsmobile that was nowhere to be seen. The car and its occupants, Edward and Stephania Andrews of Arlington Heights, all disappeared after a downtown cocktail party in May 1970 and haven’t been seen since, despite multiple search efforts by law enforcement.

The condition a car is found in depends on a number of things, they said: the pH of the water and the vehicle make and model, among other things. In the Chicago River, regular dredging is also likely to contribute to the cars’ breakdown as they sit on the river floor. Bussick said Scheper’s car was in pretty good shape, considering it had been submerged for 40 years.

For the yellow Oldsmobile that had been carrying the Andrewses, Grubbs wasn’t necessarily optimistic, particularly given the dredgings.

“If it’s anywhere in the channel, it’s going to be a mangled mess,” he said.

They were seeking nine other cars in the river that had all gone missing with their drivers as long ago as 2003 and as recently as 2019. Among the missing were Promila Mehta-Paul, last seen in Munster, Indiana, in 2008; Hiep Luu, who disappeared from Berwyn in 2003; and Nyameka Amanda Bell, who has been missing from Evanston along with her gray Volkswagen Jetta since 2016.

“With 97 cars, you’d think our odds would be pretty good,” Langos said.

Langos, 26, said he’s been diving since he was 11. For the last five years, he’s run his own dive recovery business and YouTube channel, finding people’s lost items underwater. The Port Barrington resident said he was drawn to the business for the feeling of “treasure hunting.”

“I don’t like the sightseeing, like a lot of people do, going to the Bahamas or something,” he said. “I like finding stuff underwater.”

As of Thursday the dives hadn’t yielded any new clues for their list of cases, but they’d made some other interesting discoveries. Earlier in the week, Langos said he’d dived a White Dodge Durango at the bottom of the river farther southwest, near the Damen Silos.

“Someone’s missing that one,” he said.

The Durango — its windshield smashed, with an open sunroof and windows — had been sitting on the riverbed alongside a black Audi SUV, a white Hyundai SUV, a red Mustang and a relatively new, dark blue Acura, they said. The group had reported all the cars they’d found there to the Chicago Police Department, suspecting they had been stolen and dumped in the river.

The Audi had been reported stolen in March 2022, police sources said, the same day it had allegedly been used in a robbery.

Langos asked to start diving with Grubbs and Bussick after getting interested in diving for missing persons.

When he started working with them, he joked that they told him there was one condition: he had to say “love you, bye” every time he started a dive. It was Bussick’s thing originally — “in case that’s the last thing someone ever hears,” she said.

As Langos and Grubbs went back down to the riverbed to examine another car, Teri Spitz sat on the boat’s back deck, wearing a shirt featuring the group’s dog Maverick. The dog trotted back and forth, standing and peering out over the edge of the vessel every time Langos or Grubbs jumped back in.

Spitz, 59 and a resident of Sublette in northwest Illinois, doesn’t dive. But she heard about the group’s plan to dive for a person near her hometown and wanted to be involved.

“They bring closure to families,” she said.

A recovered steering wheel and license plates from sunken cars in the Chicago River on the Chaos Divers boat near Cermak Road, Sept. 4, 2025. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

A recovered steering wheel and license plates from sunken cars in the Chicago River on the Chaos Divers boat near Cermak Road, Sept. 4, 2025. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Spitz has traveled with the divers on and off since she first met them in Rockford, donating her time to help them with gear, caring for Maverick and other logistics. She was with them on the Ohio leg of the journey, she said, and met them again when they came to the Chicago area.

A red and white flag, notifying other boats that there were divers in the river, fluttered overhead. After the group finished with the Chicago River, they planned to head to south suburban Lynwood and the Calumet River to look for evidence in a few other cases.

Langos resurfaced with a different hunk of metal and a Buick emblem he’d pried off one of the cars beneath the boat. He examined five cars on that dive, he said, but only found what Grubbs called “answers to where they’re not.”

They come up empty a lot, Bussick said. But their first successful location, she continued, would have kept them searching even if they’d never found anyone else: “It was one of those things where it was like, ‘if this is all we ever do, this is enough.’”

Originally Published: September 6, 2025 at 5:00 AM CDT