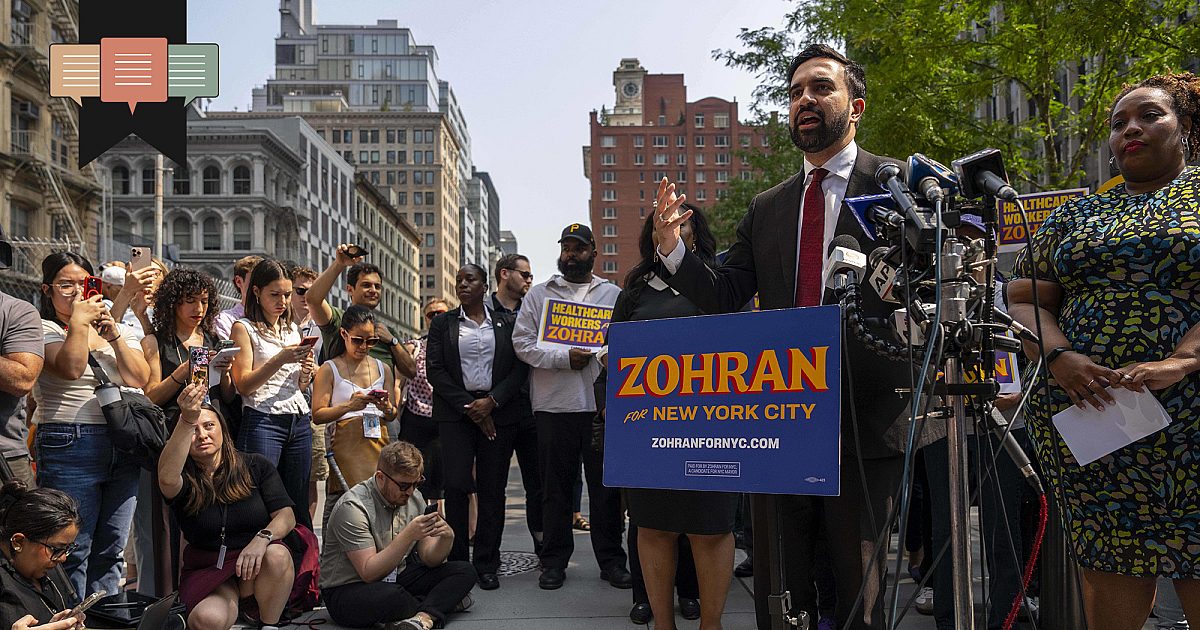

The Democratic nominee for mayor of New York City is a devout Muslim and an avowed socialist. Zohran Kwame Mamdani, a 33-year-old state assemblyman from Queens, has never hidden his religious identity. Born in Uganda and raised in New York, he fasts publicly during Ramadan and organizes iftars in solidarity with Palestine. He frames housing and labor reform not as abstract technocratic aims, but as matters of justice rooted in divine obligation. Even his socialist protest actions are carried out in the name of moral duty. His faith does not merely accompany his politics; it animates them.

To secular progressives, this may appear a triumph of pluralism. To many conservatives, it may serve as another sign of America’s political decay. But for those with theological discernment, the imagery is striking: Islam, a religion of totalizing claims, does not hesitate to govern. It enters the public square with confidence, armed with an all-encompassing worldview and an unapologetic moral vision. It rejects the myth of neutrality and understands that law is never merely procedural but is always inherently theological.

In contrast, modern evangelicalism has grown timid. What was once a public religion rooted in the lordship of Christ over all creation has been largely reduced to personal piety. Christianity, in many quarters, no longer seeks to form cultures or shape law. It contents itself with managing personal anxieties and securing individual conversions. Modern Christianity asks to be tolerated, not to be heeded.

But the gospel is not a private experience; it is a royal announcement. The Jesus we proclaim is not a lifestyle guru—He is the risen and reigning King. The New Testament declares that all authority in heaven and on earth belongs to Him (Matthew 28:18). The Church has always confessed this. The tragedy is that there are so many self-proclaimed Christians who no longer act as if they believe it.

Islam understands what many Christians have forgotten—that theology always informs governance, whether explicitly or not. When Mamdani speaks of economic justice or foreign policy, he does so with reference to transcendent beliefs. His policies may be awful, but his worldview is not random. The moral compass he employs is fixed, not floating.

Meanwhile, American evangelicalism has largely surrendered its own moral vocabulary. Formed by postwar revivalism and cultural accommodation, much of the movement has embraced a gospel that is solely concerned with individual conversion, stripped of its cultural mandate. It has exchanged the dominion of Christ for the decorum of quietism. It has denied the natural law, and in doing so, reduced Christian ethics to a sectarian concern. The result? A generation of Christians unequipped to contend for public truth and too “winsome” to try.

A faith that once shaped constitutions now blushes at the thought of saying anything political for fear of offending sensibilities.

But this retreat is not the historic Protestant posture. The evangelical Protestant tradition, at its best, has never divorced Christ’s lordship from the realm of public life. From Geneva to Puritan New England, Protestant thinkers affirmed that civil rulers are accountable to the moral law of God. Whether in Calvin’s political theology, Rutherford’s Lex, Rex, or the sermons of colonial pastors who thundered against tyranny, Christ was preached as King not just of heaven but of nations. Protestant theology taught that Scripture speaks to public matters and that moral law is not a matter of preference but of divine revelation through Scripture, conscience, and reason. Christian public theology taught that the magistrate is a servant of God, whether he acknowledges it or not (Romans 13:4).

Today, such language sounds foreign, even to many Christians. That is itself an indictment. A faith that once shaped constitutions now blushes at the thought of saying anything political for fear of offending sensibilities. We must repent of this retreat. But repentance requires more than regret—it demands recovery.

What we need is not a Christian imitation of Sharia law. What we need is a reformed, evangelical retrieval of public theology—rooted in Scripture, informed by the natural law, and framed by confessional clarity. We need pastors who preach as though Christ reigns not merely over hearts, but over all of creation. We need churches that equip believers to think Biblically about their public responsibilities. We need disciples who understand that being salt and light requires more than spiritual sincerity; it requires public engagement.

This means reclaiming the doctrine of Christ’s kingship as more than eschatological comfort. It is a present reality, with public implications. Christ is not merely Lord over Christians and churches; He is the King of kings, nations, and peoples. Christ’s rule and reign is not honored by silence. It must be confessed, proclaimed, and lived out.

If we fail to do this, the vacuum will not remain. Nature abhors it—and so does the public square. As the Mamdani campaign shows, the void left by Christian reticence is being filled by rival gods and their followers who are not embarrassed to govern.

The rise of Islam in Western politics should not surprise us. It should convict us. It reveals not merely the boldness of other faiths, but the failure of our own discipleship. A godless public square will not remain godless. The secular myth of neutrality is collapsing, and it seems that Christians are the last to recognize it.

The question is not whether religion will influence the public square. The question is: which one? Either we recognize that Christ is Lord of New York City, or others will try to give that title to someone else.