By Emily Chambliss

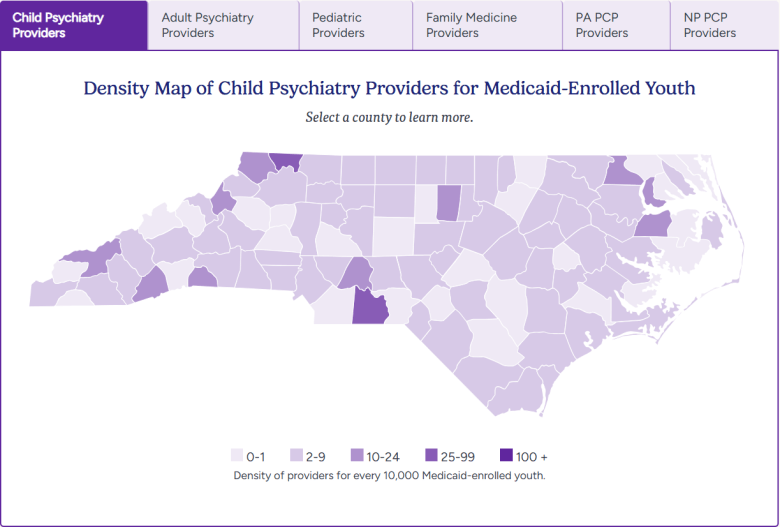

In North Carolina, the odds of finding a child psychiatrist depend too often on your ZIP code. Even in urban counties such as Wake or Mecklenburg, families may wait months for an appointment. In much of rural North Carolina, the wait is indefinite: There is simply no one to see.

Sixty-one counties lack a child psychiatrist, according to the UNC Sheps Center for Health System Research. The shortage is not new, but the urgency is. Duke University reported a significant increase in suicide-related hospitalizations for children during the COVID-19 pandemic, with as many as 50 referrals a day to specialty care. The rate has come down some since the spike in 2020, but between 2013 and 2023 (the latest year for complete data) the overall suicide for teens increased by 30 percent.

More than half of North Carolina’s 2.6 million children under the age of 19 get their health care from Medicaid, yet only about 150 child psychiatrists statewide see Medicaid patients, said Gary Maslow, a psychiatrist with Duke Health. That size workforce is unable to keep pace with demand.

“The distance between care and your home can be really far, especially the farther you are from the larger cities,” Maslow said. “It can leave psychiatric care almost entirely inaccessible for many people in our state.”

This means pediatricians and family doctors — often with little mental health training — are faced with the prospect of diagnosing complex conditions and prescribing powerful medications.

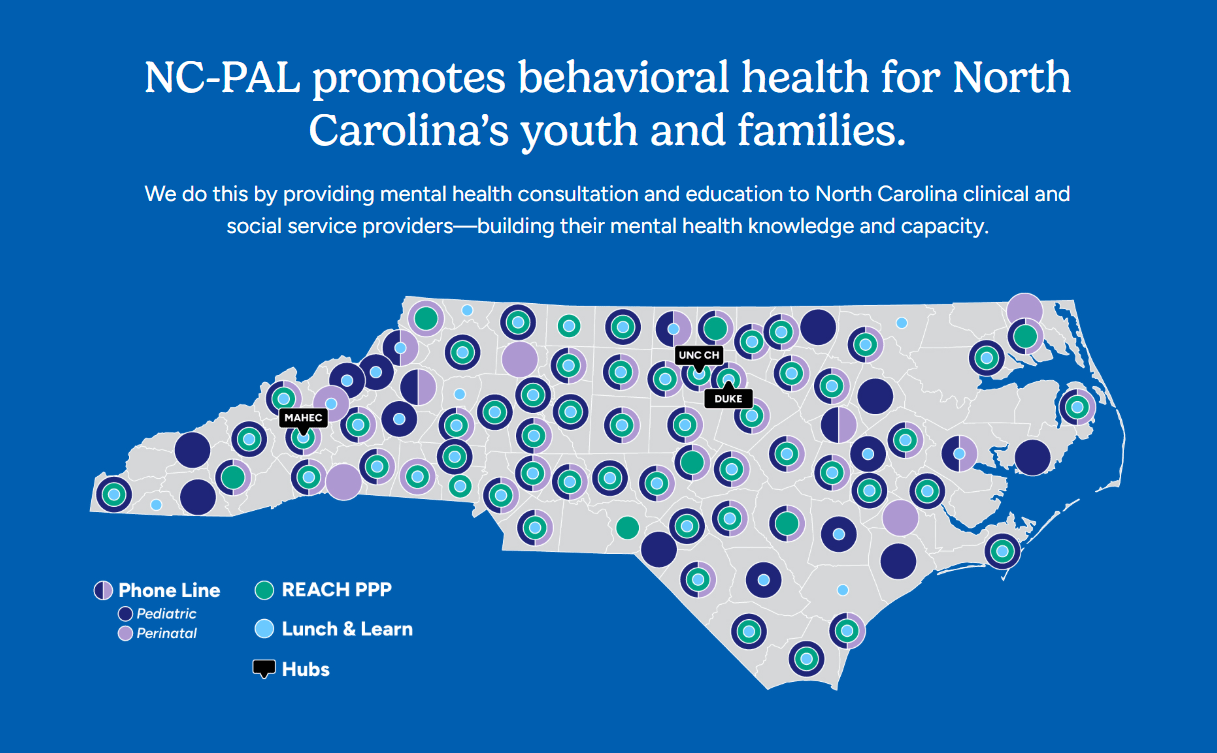

The North Carolina Psychiatry Access Line was launched in 2017 to help close that gap. Operated jointly by Duke and UNC schools of medicine with support from the state Department of Health and Human Services, NC-PAL offers a free phone line where pediatricians, family doctors and other providers can consult directly with behavioral health specialists about their patients.

‘Not fumbling anymore’

NC-PAL operates weekdays from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Providers call a central number and are first connected with a behavioral health consultant — often a social worker or psychologist — who gathers details about the case. If the issue involves diagnosis or medication, the call is transferred to a child or perinatal psychiatrist.

Maslow, who directs the program, described the approach as “consultation through education.” Providers leave the call with practical guidance they can use with future patients.

For pediatricians like Debi Best at Duke Health, that support is reassuring.

“When I call, I walk back into the room with a family and I’m not fumbling anymore,” she said. “The parents see that I have a plan, and the relief on their faces — that’s the difference NC-PAL makes.”

Training the existing workforce

North Carolina medical schools don’t have room to train enough psychiatrists to meet demand. Maslow said it would take doubling the workforce just to make a dent, so NC-PAL focuses on strengthening the skills of existing providers.

The program’s flagship initiative, the REACH Pediatric Primary Care Program, is a two-and-a-half-day course followed by case calls where participants discuss real patients with psychiatrists. More than 600 providers have completed the training; program leaders aim to reach 1,000 by 2028.

Best, who oversees REACH, said it reshaped her practice.

“It wasn’t just theory—it was skills I could take into an exam room,” she said. “I felt like I could really serve my patients when they brought me their hardest problems.”

NC-PAL also hosts biweekly “Lunch & Learn” webinars on topics like suicide prevention, childhood trauma and medication management that draw hundreds of participants across the state. These smaller sessions are meant to keep providers engaged and reinforce what they’ve learned in formal trainings.

“These are the most impactful continuing education sessions I’ve ever done,” Best said. “I leave with tools I can actually take back to my patients the next day.”

Program analysts also evaluate whether training changes how providers prescribe medications. That includes looking at whether antidepressants or ADHD medications are being used more appropriately after training.

“We don’t just want providers to feel better — we want to know that kids are actually getting better care,” Maslow said. “When you look at prescribing patterns before and after training, you can see that shift.”

By tracking this data, NC-PAL leaders say that their training can support providers in the moment and lead to measurable improvements in the quality of care families receive.

Closing the rural gap

Despite training and a dedicated phone line, reaching rural communities is still a challenge for NC-PAL.

Maslow said that while NC-PAL fields thousands of calls, many providers who could benefit from the service don’t know it exists.

“It can be hard to get people to call,” he said. “We have 250 training slots a year and a phone line open five days a week — we just need more people to use it.”

To close that gap, Maslow hired regional consultants who work directly with physicians in underserved areas. In its early years, outreach was simple: Staff drove county to county, doughnuts in hand, just to start conversations in clinics.

The strategy has expanded. Today, NC-PAL partners with Departments of Social Services, schools and child care centers in western and eastern counties. By working through these institutions, the program reaches families who might never hear about it from a doctor’s office.

After the remnants of Hurricane Helene tore through Western North Carolina in 2024, NC-PAL shifted resources to the region. Staff set up office hours where teachers, therapists and parents could come in, share what they were experiencing and get immediate support.

“It was a chance for people just to sit down and talk through what they were seeing — in their children and in themselves,” Maslow said. “Sometimes the most valuable thing we could do was listen and point them toward the right next step.”

Alongside office hours, NC-PAL organized trauma-focused Lunch & Learn sessions. The training aimed to help providers in the region recognize how trauma might appear in children after a disaster and what responses could ease the burden.

“The hurricane was a tremendous trauma — not just for the kids, but for the adults who were supposed to be their helpers,” Best said. “Teachers, early-intervention specialists, even parents — they were shaken too. We tried to be present for all of them.”

NC-PAL rolled out several initiatives to support hurricane recovery in Western North Carolina. One is a two-hour “CARE” training for school staff, therapists and other adults who work with children. In the sessions, participants learned how to recognize signs of trauma — especially in kids with developmental disabilities, who often process and respond in different ways.

NC-PAL providers also pivoted to offer in-depth assessments for children hit hardest by the hurricane. Clinicians look closely at a child’s medical history, mental health symptoms and trauma experiences. The goal is to spot serious needs early and create treatment plans tailored to each child and family.

“Some of these kids went through unimaginable things,” Maslow said. “They need more than reassurance. They need careful assessment and treatment plans to move forward”.

The NC-PAL network is also growing to include a network of family partners — parents and caregivers with lived mental health experience who can mentor and support other families facing similar challenges.

“We want parents to feel like they’re not alone,” Maslow said. “Sometimes the most powerful thing is hearing from another caregiver who has walked the same path.”

Maslow said plans are for NC-PAL to continue supporting Western North Carolina as the region recovers, building capacity in schools and clinics so that trauma-informed care becomes widely accessible.

This screengrab shows the density of child psychiatry providers for Medicaid-enrolled youth in North Carolina. Credit: NC-PAL

This screengrab shows the density of child psychiatry providers for Medicaid-enrolled youth in North Carolina. Credit: NC-PAL

Measuring impact

Since 2017, NC-PAL has taken more than 6,000 calls from roughly 1,700 providers across 90 counties, Maslow said. He also said the calls cover pediatric and perinatal cases, with consultations provided to more than 1,000 pediatric providers and around 700 practitioners serving pregnant or postpartum patients.

The program has received support from the state legislature in the recent past; the General Assembly allocated a total of $3.8 million in recurring dollars to NC-PAL in the 2023-24 budget. (This year there was no new state budget, meaning that allocations from the prior fiscal year recur in the new budget cycle.)

Evaluations presented to the North Carolina Psychiatric Association found that nearly every provider who used the line said their questions were answered promptly. More than half reported greater confidence in treating children with mental health needs after the consultation, Maslow said.

“By the time I hang up, I have a clear plan,” Best said. “I can look a family in the eye and say, ‘We’re going to try this, and I feel good about it.’”

Maslow said that consultations helped avoid some emergency department visits and psychiatric hospitalizations, but the program cannot overcome the state’s profound lack of specialists.

“Even if every psychiatrist worked around the clock, we couldn’t meet the need,” he said.

NC-PAL is part of a growing national network of psychiatric access programs, now operating in most states. Massachusetts established the Child Psychiatry Access Program, which offers telephone consultations and care coordination to support pediatric providers statewide. Additionally, Texas has expanded child psychiatry training and placed residents in community clinics. For now, North Carolina continues to rely on NC-PAL as a bridge to compensate for its limited psychiatric workforce.

Support and sustainability

NC-PAL is supported through Medicaid, state appropriations and a federal Health Resources and Services Administration grant, given to improve access to health care for people who are isolated, uninsured or medically vulnerable.

The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services contracts with Duke University to run the program, with UNC as a subcontractor. Stacie Forrest, the child behavioral health manager with the state’s Division of Child and Family Well-Being, described it as “one of my favorite contracts that we have.”

“We want children in North Carolina to thrive and be healthy, and part of that is getting access to good psychiatric care,” she said.

She added that the program has expanded over the years beyond the call line to now work with local county Department of Social Services offices and child development centers, depending on need.

“One of the things that NC-PAL has done well is listen. They ask for feedback, they engage local communities and they try not to take a blanket approach,” Forrest said. “Instead, they respond to what each community actually needs.”

While the program is among the best funded in the country, Maslow said, resources alone are not enough. Outreach is an ongoing challenge, especially in rural counties where providers may not know the service exists.

“You need more people to do this work, not just support. Training and consultation can fill part of the gap, but the gap is still there,” Maslow said. “You can see the difference in the quality of care patients receive and in the confidence providers have in addressing these conditions. We’re proud of that, what we’ve seen so far.”

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.