Tabitha wanted precious few things when she walked out of the Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility in Cañon City on July 21, 2022.

She wanted to be who she’d become within the walls and barbed wire fences of the prison. She wanted to be the parent she hadn’t been for the 18 years she was incarcerated. And she wanted to “succeed in life and never go back.”

Tabitha, who asked to be identified only by her first name because she is working to rebuild her life, had served time for a felony conviction she chooses not to explain other than it was not a financial crime. She does say she transitioned into her true gender in prison. “I did a lot of soul searching on the inside, really trying to figure out who I was and what made me make those choices that brought me to that point in my life,” she said. And one thing she learned “is that I embrace all of the decisions of my life, the good and the bad, because I wouldn’t be who I am if you took any single decision away.”

But when she left, she was like thousands of people released from federal prison each year who try, and fail, to find gainful employment.

A 2022 report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that of more than 50,000 people released from federal prisons in 2010, a staggering 33% found no employment at all over four years post-release, and at any given time, no more than 40% of the cohort was employed.

Around 60% of formerly incarcerated people experience joblessness at any given time, the report says. And that’s a big reason the recidivism rate for the 6,000 people released from prison in Colorado each year stands at 28%, according to the Common Sense Institute.

Two of the biggest barriers to finding employment are homelessness and lack of transportation, according to the Colorado Department of Human Services.

Convictions can also show up on background checks for the rest of a person’s life, and “if they’re up against an applicant that doesn’t have a conviction in their background, they’re probably going to not be the one selected,” said Mark Smesrud, regional director for social enterprise at the Center for Employment Opportunities, which partners with the Colorado Department of Human Services to help people exiting the justice system find jobs through their ReHire program.

“They’ll nail an interview, and (the employer) is like, great, we love you, we’re gonna run a background check and get back to you,” he said. “So someone can have so much hope, be on the highest of highs and then they come crashing down” when the subject of their background comes up.

As the Bureau of Justice statistics data shows, that yo-yoing can drag on for years, pulling people into depression and suicidal thoughts. It takes money to eat, get around and find housing, and for a population seven times more likely to experience homelessness after incarceration and twice as likely to die by suicide due to “the daily dehumanization inflicted on incarcerated people (by correctional staff and administration) and lack of opportunities postrelease,” according to Noel Vest, a formerly incarcerated scholar at Boston University’s School of Public Health, it can be too much.

Tabitha and “the dreaded background check”

Tabitha has two bachelors degrees: one for programming information systems and one in biology. She also worked a number of jobs in prison, including “the stereotypical one you always saw in the movies. I made license plates: hand pressed them, painted them, packaged them.”

So with her education and job experience, when she began her job search, she thought, “I’ll get a job. You know, not a problem. I just had the confidence when I walked out that I was going to do it.”

But after about a month of “no thank you, we decided to move on without you,” she was starting to worry, she told The Colorado Sun. “I had a little bit of money saved up, and I happened to be renting a bedroom in a condo, but I was starting to get very concerned and disheartened.” It came down to the dreaded statement: We need to do a background check.

Finding a conviction on someone’s record, especially a felony, is where many employers hard stop when interviewing a candidate, Smesrud said.

Tabitha poses for a portrait in her office at the Center for Employment Opportunities on Friday, Sept. 5, 2025, in Denver. (Andy Colwell, Special to The Colorado Sun)

Tabitha poses for a portrait in her office at the Center for Employment Opportunities on Friday, Sept. 5, 2025, in Denver. (Andy Colwell, Special to The Colorado Sun)

And even if a formerly incarcerated person does happen to find an employer, it doesn’t mean they’re on the road to success. If they’re on parole, and they want to stay in compliance with their parole requirements, for instance, they might make it through the gantlet of the hiring process, agree to a start date and then have to tell their new employer their schedule conflicts with a class, check-in or urine test they’re required to take during normal working hours, and the employer might rescind their offer, he added.

If that ends up happening, the person might go back to their parole officer, explain the situation, “and the PO will just say, ‘Go find another job,’” Smesrud said. “I mean there are always exceptions … but it’s kind of a rock and a hard place for people on their reentry journey.

They want to stay in compliance with their parole requirements, but they also need to make money and pay rent, buy food and take care of themselves, right?”

Oftentimes, people are sent back to prison on technical violations, not necessarily new offenses, he added. “They’re out of compliance with their parole, and in a lot of instances, it’s because they’re just trying to make it right. And when there are new offenses, it’s frequently when their past convictions, their parole requirements and all these other things are so oppressive they can’t get a job, and they need to survive, so they turn back to a life they’ve known,” which often involves crime.

But the Center for Employment Opportunities and other organizations are trying to help.

Helping the formerly incarcerated get back on their feet

Work re-entry programs available through ReHire include Catholic Charities, Diocese of Pueblo, which serves Pueblo, Fremont, Las Animas and Huerfano counties; Goodwill of Colorado, with locations in El Paso, Teller, Douglas, Jefferson, Denver, Arapahoe, Adams, Boulder, Broomfield, Larimer and Weld counties; CrossPurpose, serving Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Denver, El Paso and Jefferson counties; The Center for the Development of Economic Equity in the Denver metro area; and the Center for Employment Opportunities, which serves Denver, Colorado Springs, Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Broomfield, Denver, Douglas, El Paso and Jefferson counties.

They’re funded in part by the Department of Human Services which partners with state and local Department of Corrections as well as other community providers to target that population.

The organizations provide wage-paying work, job skills training and supportive services. They coach their clients on how to obtain different job certificates and identify skills they picked up in prison that can translate to other jobs when they’re out.

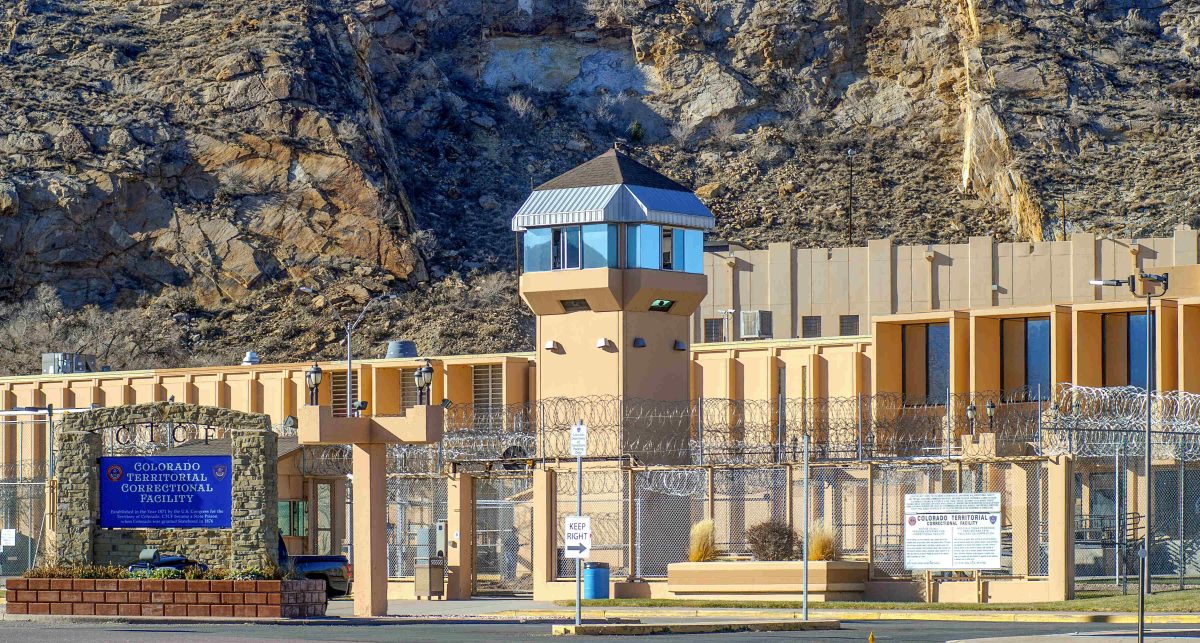

Located in Canon City, the Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility, shown here in a Dec. 9, 2020, photo, is the state’s oldest prison. Built in 1871, it preceded the state’s admission to the Union by five years. (Mike Sweeney, Special to The Colorado Sun)

Located in Canon City, the Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility, shown here in a Dec. 9, 2020, photo, is the state’s oldest prison. Built in 1871, it preceded the state’s admission to the Union by five years. (Mike Sweeney, Special to The Colorado Sun)

And they teach them how to explain to an employer that even though they may have a record, they’ve addressed what’s in it and their skills would be a valuable contribution to the employer’s team.

The employment and training program is a 50% federal reimbursement program, meaning in order to draw down a federal fund to provide employment and training services to populations like returning citizens, the Department of Human Services must find organizations in Colorado that can contribute the 50% non-federal funding.

CEO, a national nonprofit with programs in 30 cities, is one of those organizations. And a new report by the Colorado Evaluation and Action Lab at University of Denver that evaluates CEO participants’ earnings pre- and post-enrollment shows they are making big financial gains through its life-changing support.

The power of a fresh start

Tabitha found CEO the first day she met with her parole officer, because CEO was holding an orientation at the office.

So she “went ahead and did the orientation” before setting out on her own search for employment, she said. That’s when she got all the no thank-you’s.

After around a month, she called a representative she’d met from CEO and “almost immediately” he helped get her into the program.

It wasn’t glamorous work at first: All CEO participants start out doing “community beautification projects” like picking up trash or repainting certain areas around cities, and Tabitha said it was “an extremely humbling experience.”

“My previous self was proud, arrogant, and I’d see people doing (trash duty) and think they were deadbeats,” she added. “But then doing it myself, I realized, no, they weren’t deadbeats. They were doing what they needed to do to survive. Rather than being a deadbeat, they were working, and it really taught me a lesson.”

CEO guarantees every participant who completes the brief, paid orientation up to four days a week of transitional work for a liveable daily wage.

Staff also assists each participant in assembling the documents necessary for employment and eligibility for benefits such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Following orientation, participants continue to take workshops and get one-on-one support covering crucial digital skills, financial literacy and workplace and communication best practices.

“Having a job is freedom,” says Tabitha, who became a full-time employee at the Center for Economic Opportunities around a year after she exited the prison system. Her employer calls her work ethic, diligence and passion for CEO’s mission to help formerly incarcerated people re-enter the workforce, “phenomenal.” (Andy Colwell, Special to The Colorado Sun)

“Having a job is freedom,” says Tabitha, who became a full-time employee at the Center for Economic Opportunities around a year after she exited the prison system. Her employer calls her work ethic, diligence and passion for CEO’s mission to help formerly incarcerated people re-enter the workforce, “phenomenal.” (Andy Colwell, Special to The Colorado Sun)

The average cost of participants in the ReHire program is around $3,200 per person, but once they find employment, there’s a return on investment into the community, according to a study by the US Chamber of Commerce showing that connecting 100 justice-impacted people to jobs would yield $1.9 million in additional wage tax contributions and $800,000 in additional sales tax revenue over the employee’s lifetime.

During her training, Tabitha won a scholarship for talent acquisition training in CEO’s Emerging Leaders Program.

She learned to use Google, continued to review and revamp her resume and practiced answering “the dreaded question” about her background.

She was still facing the barrier of having a felony “even though it’s been proven that a person with a felony actually makes a better employee,” she said. “They take less time off. They’re motivated to keep that job to stay out.”

Eventually she did get a job offer from an employer at an insurance company even after they found out she was on probation and parole. When she said she had a felony, the employer asked if it was a financial felony. “And I said ‘absolutely not.’ I said ‘do you want me to start Monday?’ And the employer said ‘yes!’”

She worked there until someone bought the company and changed the policy from a no-financial felonies to no felonies whatsoever.

But CEO broke her fall again, putting her on a standby cleanup crew.

Smesrud said he met Tabitha at the orientation she did back in 2022, and later found her to be a “great worker” on the trash cleanup crew. When they brought her into the office for her Emerging Leaders internship, he said “she knocked that out of the park as well.”

So when a full-time job matching her experience opened, CEO hired her as a full-time employee, on May 30, 2023.

Smesrud praises “her diligence, her work and her passion for CEO’s mission.”

And Tabitha says “having a real job, it’s freedom. It has enabled me to buy a home with my brother. I got a car. I have my little fur baby. It’s enabled me to live a life I’ve never dreamed I could ever live.”

Type of Story: News

Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.