Run Over by Big Car

David Obst’s New Book Details

How Lead in Gas Drove Us All Crazy

By Nick Welsh | Photos by Ingrid Bostrom

September 11, 2025

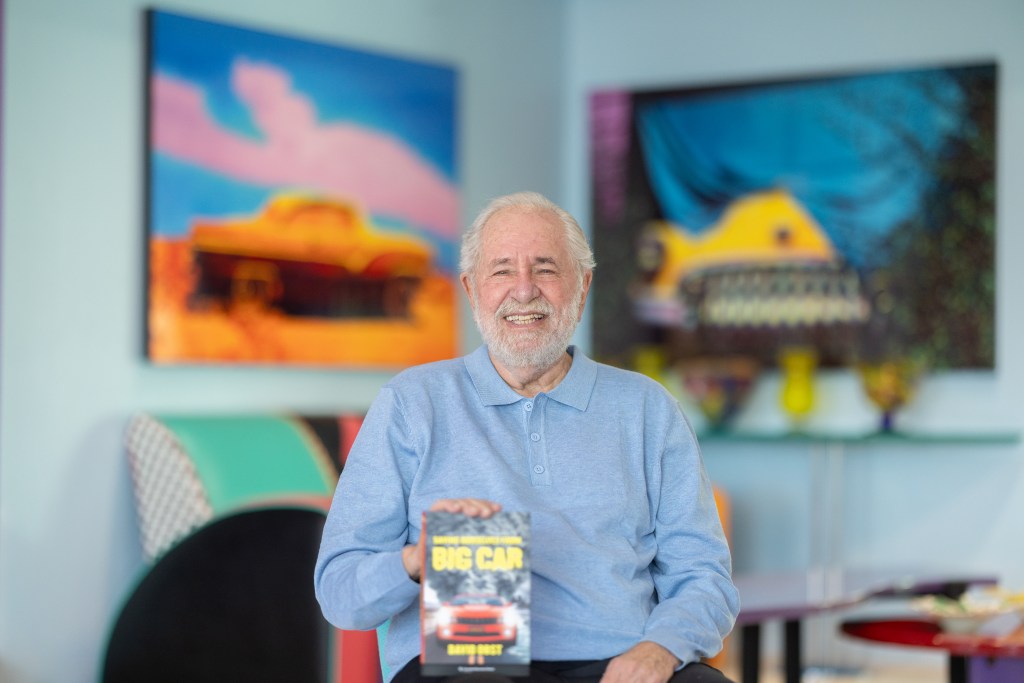

David Obst | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

David Obst | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

David Obst remembers exactly where he was and what he was doing when the lightbulb went on in his brain. Obst — a writer, literary agent, inveterate yarn spinner, and agitator-without-a-portfolio — was driving his granddaughter Sunny — 60 years his junior — from his home in Santa Barbara to Los Angeles.

Somewhere outside of Ventura, Obst recalled, he and Sunny hit gridlock. Or more precisely, gridlock hit them. Suddenly, Obst found himself utterly devoid of his customary Zen aplomb. “I hate traffic jams,” he erupted. “I hate traffic.”

His granddaughter — having perhaps heard some of this before — turned his way. “Papa,” she said, putting him on notice, “you are the traffic.”

That shut him up. At least for a moment.

“How did that happen?” Obst wondered. “How did I become part of the problem?”

That was four years ago.

During those years, David Obst — a card-carrying Baby Boomer accustomed to being part of the solution — has dedicated his sprawling curiosity to exploring that very question.

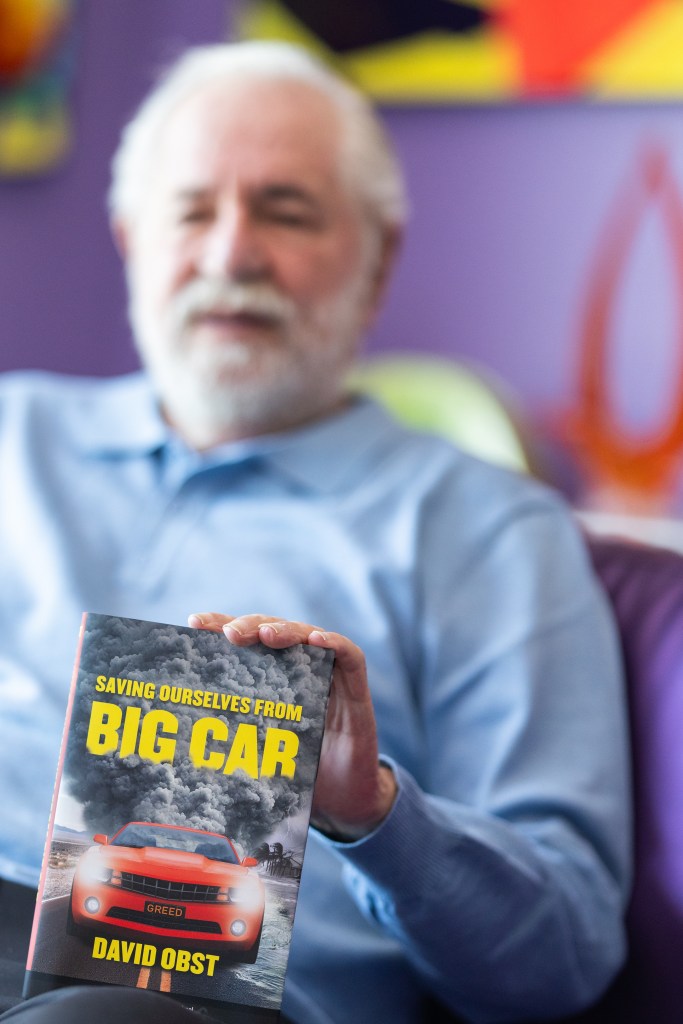

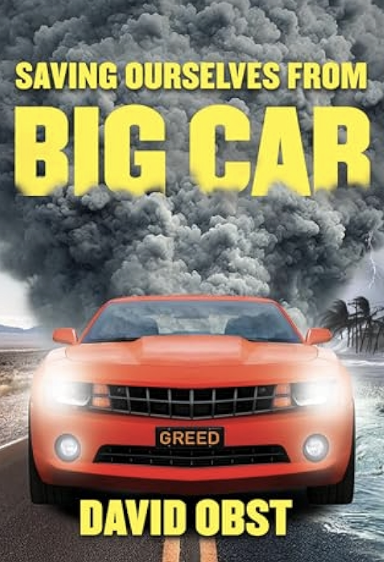

Three of those years he spent researching and writing the book Saving Ourselves from Big Car, a 300-page jeremiad on the environmental and political evils of what he terms “Big Car.”

Today, in year four, Obst — now 80 — has finished cranking out all the documentation his publishers at Columbia University Press required to demonstrate he knew what he was talking about. “Nothing in there is made up,” Obst said in a recent interview at Via Maestra 42. “Everything is backed up with sources. Nothing is just my opinion.”

His answer to the big question “What happened?” is simple. Nothing “just happened.” In Obst’s cosmology, corporate greed, self-interest, and duplicity play a primary role in shaping human affairs as manifested in Big Car.

The undeniable convenience, freedom, and opportunity that cars offer is literally killing us, he writes: “Over 1.3 million humans are killed a year because of Big Car. The total number of people killed by cars in the 20th Century — in excess of 60 million — is equal to the total number of people killed during World War II. Efforts to make driving safer — take the laws requiring seat belts — were bitterly fought by Big Car, as were softer dash boards and collapsible steering columns that might otherwise impale a driver upon impact.”

But Obst also acknowledged that the car-buying public has often been its own worst enemy. They too fought mandatory seat belt rules. The one and only company — Nash — that voluntarily added seat belts confronted a powerful backlash from customers who wanted them gone.

As a writer, Obst is easy, breezy, and brazenly conversational. In person, he radiates wonder and delight, even when warning about the impending environmental Armageddon. Obst is one of those genuinely rare creatures, an apocalyptic optimist. In person, the weight of his enthusiasm tilts far more to how we’re going to get out of this mess than to how we got into it.

The thrust of his written narrative, however, goes in the other direction.

David Obst | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

David Obst | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

Above all, Obst is a storyteller; his eyes light up while recounting one outrage after the next. It’s like he can’t decide whether he’s horrified or having fun. When in storytelling mode, Obst cannot be budged off point. Ever. If successfully interrupted, however, Obst politely waits it out. Then he starts up precisely where he left off. Never will you hear David Obst say, “Now, where was I?”

The expression “Big Car” refers to a “ghoulash” of special interests made up of car manufacturers, tire makers, the insurance industry, the steel industry, Big Oil (of course), the advertising industry, lobbyists, and machine tool manufacturers. In 2020, Obst says, these groups combined spent $400 million on political campaign donations, outpacing the environmental opposition by a margin of 13-1.

Then there are the legions of traffic engineers — high priests of the grid — whose mantra, Obst says, has been “more, wider, and faster” when it comes to building roads than resolving any congestion issues. Such solutions, he says, prove short-lived and more expensive. Typically, they just make things worse.

And of course, he points out, it was President Dwight D. Eisenhower who powered through the legislation needed to create the federal highway system back in the 1950s that enabled America’s postwar real estate boom to really explode. Eisenhower sold the bill on the pretext of national security. As a result, all freeway underpasses still must be built high enough to accommodate flatbed trucks hauling a regulation-size ICBM missile.

True fact. It’s just one of many Obst has at his fingertips.

Another one Obst especially likes is that in 1904, New York City had 130,000 horses, then used for transportation purposes. Each one of those horses, Obst will tell you, deposited 24 pounds of manure and released 12 gallons of urine each day. The cumulative stench and debris thus generated, he explained, provided the impetus for the invention of the car. The first wave of cars was electric, he noted; next came steam. The internal combustion rolled in last but has never gone away.

Saving Ourselves from Big Car is permeated with stuff that’s just plain cool to know. But at certain saturation levels, it can get overwhelming. Did you know, for example, that in 1903, a woman inventor patented the windshield wiper? But because no car makers were interested, her patent expired before she could make a dime. And are you aware that by 1950, the United States was making 75 percent of all cars manufactured on the planet?

But where the book’s heart really beats — or breaks, more aptly put — is in telling how a consortium of auto makers, oil companies, and chemical manufacturers conspired to add lead to car gasoline, even though they knew that lead exposure inflicted irreversible brain damage, induced hallucinations, triggered heart attacks, sparked convulsions, and resulted in premature death.

The automotive virtue of leaded gasoline was hardly insignificant, however: It provided much more power, better mileage, and dramatically smoother rides — no pinging or hiccupping to mar the industrialized magic of the internal combustion process. But the price paid by those breathing all this lead-infused air — “looney dust,” as it was termed in the tabloid press of the 1920s — still defies calculation or moral reckoning.

According to the World Health Organization stats Obst cited, 1.3 million people a year die from lead poisoning, much of it airborne. “Lead killed more people than the Nazis ever did during World War II,” Obst said. “No one has ever been held accountable, and no one was ever charged with a crime.”

Even so, an executive with the Ethyl Corporation would complain in the 1970s, the harassment and persecution of his company by environmental critics and health professionals was “the worst example of fanaticism since the New England witch-hunts.”

For the record, there had been high-profile hearings in the 1920s and later in 1960s — both sparked by alarms raised by genuinely heroic scientists — but they went nowhere. Scientific “experts” working for the corporate entity creating the lead additives assured the powers-that-be that the lead posed no greater health threat than water and attacked the crusading skeptics as anti-business hysterics.

Most damagingly, all relevant data on exposure levels and health risks were kept from the public under the lock and key of corporate confidentiality.

It’s the same playbook Exxon would later use to cynical perfection when spending millions to rebut the existence of climate change after having perfected the science that actually proved its reality.

The long and sordid saga of leaded gasoline came sputtering to its much-delayed end in the mid-1970s. As in all major world affairs, events in Santa Barbara played a small but essential role. It was the Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969 that triggered the creation of the Environmental Protection Act and the passage of the Clean Air Act. These led to a regulation mandating that all new cars be equipped with catalytic converters.

As gas station operators would learn the hard way, catalytic converters and leaded gas didn’t mix. In fact, the combination was death on engines. Cars had to be towed from gas station lots. That’s when oil companies making gasoline knew it was time to get the lead out. Lead-infused gas was — and is — still sold. But the gas pump nozzle delivering leaded gas has been sized to be too big for cars requiring lead-free gas.

Obst is not just another arm-chair environmentalist desperately tossing out Hail Mary passes to save the planet. He boasts a résumé anyone could brag on. The oldest of three kids in a Jewish household, Obst grew up in Culver City. His mother was the daughter of Ukrainian immigrants by way of Minneapolis, and his father was the son of German Jews by way of the Bronx. They met in Los Angeles during World War II, where Obst’s father, a soldier, was a stationed. His mother, a real-life Rosie the Riveter, had moved to L.A. to work in a factory that made airplanes for the war effort. The two met at a USO dance. Right away, they clicked.

After the war, Obst’s father, who worked in advertising, made a point of driving a new Cadillac. It was good for business. The family was solidly middle class. But despite his southern California upbringing, Obst never got sucked into the automotive delirium of car culture. As a kid, he happily rode a bike. He recalls it being a 10-speed. With a derailleur, no less. He went everywhere. Venice Beach. But he doesn’t remember what make it was. Or what color either.

He’s similarly oblivious about the cars in his life.

He does, however, remember the ’60s. And everything about them. He remembers getting manhandled by Chicago cops during the Democratic Convention of 1968. Soon after, he went to Taiwan, where he interviewed American missionaries on a grant he mysteriously received from Stanford, a university he did not attend. On the strength of this field work, Obst was admitted to grad school at UC Berkeley without ever having graduated any four-year college. Over the years, Obst lived in New York and Washington, cities in which cars are either a hindrance or strictly optional.

David Obst | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

David Obst | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

In the early 1970s, he set up shop in the nation’s capital, starting a fledgling news service with a distinctly counterculture bent. One of his neighbors was a reporter named Seymour Hersh who would become famous for exposing that U.S. troops killed 504 civilians — women, children, and old men — in the Vietnamese village of My Lai.

At first, no major news organizations would touch the story. It was too outrageous to be believed. Hersh enlisted Obst to help him reach out to every editor and publisher in a directory of American publishers and editors. Obst — imbued with an improvisational swagger then yet to be justified by either experience or accomplishment — went to work. He began cold-calling newspapers across the country, parlaying the interest of the Hartford Courant’s editor into what Obst interpreted as a done deal and convinced 40 other papers across the country to print the story on the same day.After that, about 30 major news publications and TV outlets picked it up. And then, it blew up. Hersh quickly became a journalism icon of shoe-leather determination. My Lai became an icon for everything that was wrong about the war.

Obst’s role didn’t go unnoticed. When Daniel Ellsberg, a Rand Corporation analyst, started leaking copies of the now infamous Pentagon Papers in 1970 — 3,000 pages of confidential federal documents that exposed just how much various administrations had lied to the American people about the true reasons for the war, how the war was being waged, and whether it was even winnable — Obst played a small, supporting role helping to get a few copies into the hands of reporters. When Ellsberg was indicted. Obst was informed he would be given “use immunity,” meaning he would have to testify against Ellsberg or face criminal sanction.

Rather than be a rat, Obst fled the country, spending three weeks in Iraq, Kuwait, and several other Middle East countries before his parents notified him it was safe to come home. A federal judge dismissed the charges against Ellsberg when it came out that President Richard Nixon had approved the break-in of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist office without a warrant.

A few years later, as the Watergate scandal was erupting, Washington Post reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward went shopping for someone to publish what would later become their best-selling book — and subsequent movie — All the President’s Men. Given Obst’s track record, it’s not surprising they asked him to represent them as their agent.

How he pulled it off is one of those swirling cocktails of a story. As Obst tells it, he and the project were widely rejected. Eventually, he was at a meeting with his last hope for a publisher. When he got turned down, Obst collapsed in front of the poor man. “I did something I’ve never done,” he said. “I cried. And not just a little. Loud, wailing nonstop tears. I mean, I really cried.”

Apparently, tears work.

After that, Obst was made.

Not all his work was so edgy and politically confrontational. In 1984, he went to New Orleans with a Hollywood executive on a trip he described as “debauched.” To justify the trip, the executive asked Obst to conjure some movie ideas. “I blurted out Revenge of the Nerds,” he said. Then he and a couple of writer friends came up with the tagline, “Time for the odd to get even.” While the film never cracked anyone’s Best 100 Films lists, it did plenty well enough, spawning three sequels.

Little wonder that for all he knows, David Obst — the literary agent, the activist, the writer — still remains an optimist. When it comes to climate change, he recognizes the human species has one foot on a banana peel and the other planted firmly in midair. Even so, Obst maintains hope. Not the preachy kind, but the roll-up-your-sleeves kind.

The last chapter of his book details 10 cities around the globe clawing back their collective spaces from the primacy of the automobile. Yes, there are the obvious ones, such as Copenhagen and Portland, Oregon. But there are less obvious ones too, such as Dubai and Taipei. And, even less obvious still, a large chunk of downtown in Salt Lake City. And a large private development in Tempe, Arizona.

Where Obst really found religion, however, is with a model out of Helsinki, Finland, known as MaaS, short for Mobility as a Service. Launched 15 years ago by a consortium of private entrepreneurs, the plan was to create an app-powered, multi-modal transportation system that would allow customers to plot their course from Point A to B via a fully integrated network of independently owned buses, vans, trains, e-bikes, regular bikes, scooters, taxis — what have you — without having to rely on a car. With one ticket, users could use any of the above services. Obst was so inspired by the published results, he got on a plane — something he rarely does — and flew to Helsinki.

At his stage in life, Obst might be inclined to stick his elbow out his car window and breathe in the ocean views. “My next plan is to make Santa Barbara a car-free city,” he said. He said he intends to enlist UCSB, the Metropolitan Transit District, and Santa Barbara City Hall in the effort.

Sounds far-fetched? You bet.

But with Obst involved, you can’t rule anything out.

Now that his book is in the stores — four long years in the making — what does his now 20-year-old granddaughter think? Sunny, after all, was the one who goaded him into action. “She doesn’t give a damn,” Obst laughed. “She doesn’t even have a driver’s license.”

An Edited Excerpt from David Obst’s New Book,

Saving Ourselves from Big Car

Let’s take a quick look at why lead is such a pernicious substance. Lead poisoning, also called plumbism, is a form of metal poisoning by lead entering the human body. It can have severe effects on the brain, as lead mimics calcium and disrupts critical processes necessary for brain function. Over time, as lead accumulates in the body, it triggers irritability and memory problems; if exposure continues, it can lead to anemia, seizures, comas, and even death. Lead is a cumulative toxicant that poses significant risks, particularly for young children. Lead doesn’t just target the brain — it also accumulates in teeth and bones. No safe threshold of lead exposure has been identified.

But humans are resilient…. Sometimes one or two individuals can change everything for the better. That’s what happened with lead….

One of the true scientific superheroes of the twentieth century was … Clair Patterson. An accomplished professor at Cal Tech, Patterson … was one of the scientists responsible for discovering how to accurately determine the exact age of our planet by radiocarbon dating of organic material.

His experiments also introduced him to lead. He realized that all his samples had way too much lead in them. Where was it coming from? In 1965, he went to Antarctica and began taking ice-core samples. Amazingly, ice samples from 100 BCE were now fully contaminated by lead….

He was finally able to publish a paper called “Contaminated and Natural Lead Environments of Man.” Despite being published in an international journal, it got virtually no attention except from the notorious Robert Kehoe. [A scientist for the Ethyl Corp who had hidden all his research on lead additives,] Kehoe unleashed the power of Ethyl Corporation against him. …But Patterson refused to back down….

In no time, things got very dicey for him. His contracts with almost every research organization in his field were abruptly ended …. Unfortunately for Patterson, one of the big shots at Cal Tech was also a board member of Ethyl Corporation. He had reminded Patterson’s boss that Ethyl Corporation had been extremely generous to the University, and he’d hate to see the relationship end.

Patterson was a tenured professor, so his boss couldn’t really fire him. But without any means to fund his research and with the University not assisting him, he was, in academic parlance, screwed….

Patterson packed up his equipment and went into exile up in Lake Tahoe. This was one of the most fortunate occurrences of the last century.

One should never underestimate the power of the revenge of the nerds. Rather than feeling sorry for himself, Clair Patterson redoubled his efforts.

He continued his research in one of the most remote places in California…. He took innumerable soil samples and carefully examined them to see if they contained lead contamination. They all did!

Clair Patterson had found his smoking gun. If the lead from car exhausts had drifted over 300 miles to this remote mountaintop, how bad must it be in big cities? What was it doing to the people who lived there?

Again, Big Car tried to silence him. No reputable journal would publish his work. Kehoe called his research nothing more than a “lead herring.”

In 1962, however, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring successfully showed the world that another contaminant, DDT, was a dangerous carcinogen. Congress had held hearings; America, the media, and even our elected officials suddenly became interested in the subject. Around the same time, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall (under two presidents, Kennedy and Johnson), an early pioneer in the environmental movement, published The Quiet Crisis: A History of Environmental Conservation in the U.S.A.

Enter [Senator] Edmund Muskie … the grandfather of modern environmental legislation. As a senator, he sponsored both the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act. These two bills fundamentally established the federal government as a player in helping preserve and protect America’s environment ….

Patterson traveled to Washington. He went to see Senator Muskie, then-chairman of the Subcommittee on Air and Water Pollution and showed him the evidence he’d found that even small levels of lead would harm children. He told him about Ethyl Corporation and that Dr. Kehoe’s threshold for safe levels of lead in the human body was a lie….

It worked. Muskie was willing to hold hearings…. Ethyl Corporation, of course, was invited to the hearing held in Washington on June 15, 1966. Patterson’s testimony emphasized that most officials accepted bad science because they were too lazy to do real research or because they were making too much money from Big Car to want to disrupt things…. The incorrect data given to them was based on tests done on humans who had lived before the start of the Industrial Revolution. He also explained that lead was now everywhere. … Finally, he pointed out that it was absurd to allow the very industry that was putting lead poison in the air to oversee determining if lead poisoning in the air was a danger to the public.

It made no difference. Ethyl Corporation quickly presented to Muskie’s committee a “who’s who” of the scientific and medical establishment to reject Patterson’s assertions. Using Kehoe’s inaccurate data, they confidently pronounced the ethyl additive to be as safe as regular gasoline — even more so in that it caused engines to perform better and get more mileage, hence producing less exhaust.

In the end, the committee found nothing wrong with the product, and there was no further adverse publicity. Patterson was completely ignored, and lead contamination dramatically increase ….

The problem with recognizing the harmful effects of lead is that the contamination occurred so gradually. The millions of tons of lead released into the air were indeed making people sick, but the process was so slow that it went largely unnoticed until it was too late.

Then, on January 28, 1969, workers were pulling pipe out of a freshly drilled oil well off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, when a torrent of gassy, gray mud shot out with a deafening roar, showering the men with slime. Unable to plug the hole, they activated a device that crushed the pipe and sealed off the well. The blowout seemed over—until bubbles of gas started roiling the water nearby. Pressurized oil and gas tapped by the drilling were now flowing across the ocean floor and rising to the ocean’s surface.

Oil leaked out at an estimated rate of 210,000 gallons a day, creating a heavy slick across much of the ocean channel. A few days later, horrified Santa Barbara residents woke to find their beaches befouled with tar and dotted with dead and dying oil-drenched birds.

Then-President Richard Nixon was not, by nature, an environmentalist, except when it came to winning votes…. He showed up [in Santa Barbara] with a large media crowd and boldly proclaimed, “I don’t think we’ve paid enough attention to this…. We’re going to do a better job than we have done in the past….”

Out of the public eye, however, when told that his domestic policy successes on the environment were something he’d be remembered for, he replied, “For God’s sake, I hope that’s not true….”

Nixon and his people quickly wrapped themselves up in the environmental movement. In 1970, in his State of the Union address to Congress, he made it a centerpiece of his speech, saying, “Restoring nature to its natural state is a cause beyond party and beyond factions. It has become a common cause of all the people of this country.” He received a standing ovation.

At this very same moment, his administration was fighting to keep DDT on crops and earmarking federal funds to build the Alaskan pipeline.

Adlai Stevenson, who twice ran against Nixon, described him in a campaign speech as “the kind of politician who would cut down a redwood tree, then mount the stump to give a speech about conservation.”

Nevertheless, Nixon … rapidly proposed new regulations for auto emissions and pledged to spend billions of dollars of federal money to solve the problem.

A freeze-frame of America’s neglect of the environment at this time would have shown that we were belching over two hundred million tons of pollution into the atmosphere every year.

The centerpiece of Nixon’s new strategy was to create the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Suddenly, there was a new sheriff in town. Ethyl Corporation and Big Car would have to answer to the EP ….