With the 2025–2026 school year having arrived, families and school members are preparing their children. Community members and officials are signing and reworking legislation tailored to helping all children thrive, especially those with disabilities.

New York is home to numerous school districts, labeled by borough and then detailed specifically to the schools in those cities and neighborhoods. According to the city’s Department of Education, about 200,000 children in the public school system have Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) that help support coping with a disability that hinders their learning.

Enjoli Morris (center) with daughters Skylar (left), Winter (right), and Sanae (bottom). (Credit: Courtesy Enjoli Morris)

Enjoli Morris (center) with daughters Skylar (left), Winter (right), and Sanae (bottom). (Credit: Courtesy Enjoli Morris)

Enjoli Morris is a mom raising three special needs daughters living with autism: Winter, 11, and twins Skylar and Sanae, 9; Sanae also lives with cerebral palsy. For several years, they attended a New York City school dedicated to giving specialized instructional support to students with disabilities, yet their time there was met with hard conversations and quick decisions to be made.

“In the beginning, we were in District 75 schools and that was a little hard for her and myself because of the way they approached Winter,” Morris said. “She was dealing with dysregulation … and she was nonverbal at the time, and I did not know what direction she would go.”

NYC Department of Education District 75 schools cater specifically to special needs students living with things like autism spectrum disorders, emotional disabilities, and other challenges.

The behavior and actions taken toward Winter, who was dealing with elopement, a behavior where someone with autism leaves a safe space with their caregiver without supervision or permission, to try to help regulate her were disheartening, resulting in Winter not wanting to attend school anymore and even running away at one point, with school officials having to chase her down.

Their situation belies a problem faced by many special needs children in New York’s public school system and school systems across the country. While many are attending the schools, their families discover it is difficult for them to adjust to traditional learning environments, which ultimately leads to parents being forced to find alternatives. In the case of the Morris family, this meant specialized private school.

“Some methods they tried with Winter [were] holding her down, restraining her, not working to understand who she is as a person and why she may be dysregulated,” Morris said. “It came to a point where she did not want to go to school and would have tantrums … eventually, I had to take her out of school because it was just too much for her.”

Responding to concerns

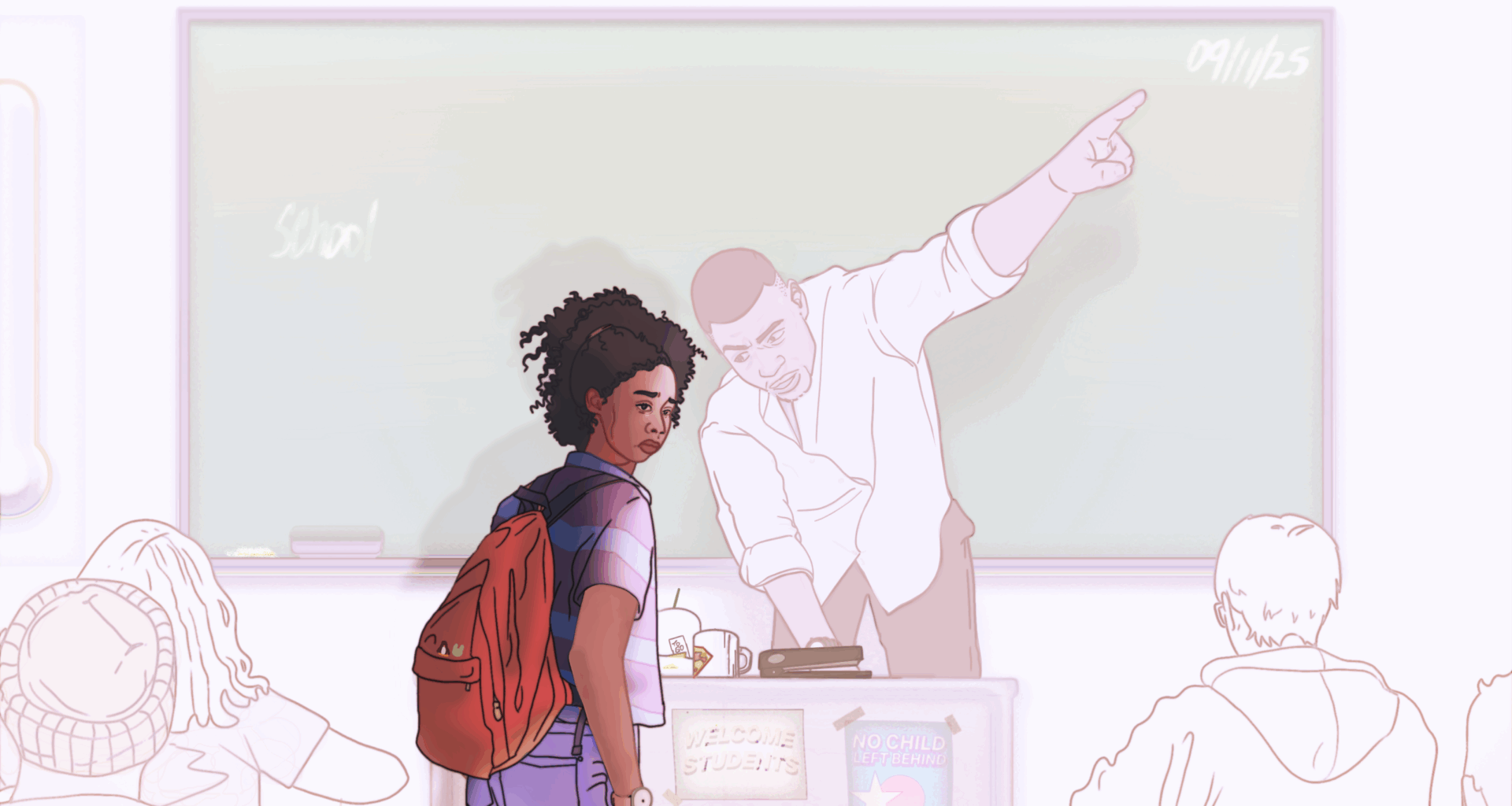

Students with emotional, behavioral, or attention disabilities are more likely to be subjected to harsher punishments and disciplinary actions, rather than positive reinforcement and second chances. According to a report by Advocates for Children staff, specific subsections of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) prohibit schools from segregating special education students from class due to their disabilities, as well as hold schools accountable for only providing students with “necessary behavioral support.”

“You have to meet these kids where they are,” said Hazel Adams-Shango, a New York City independent special education advocate and family worker. “Get down to their level and see what they need — it won’t be the same for every child.”

Hazel Adams-Shango. (Credit: Courtesy Hazel Adams-Shango)

Hazel Adams-Shango. (Credit: Courtesy Hazel Adams-Shango)

With the overpopulation of students in NYC public schools, lack of funding for public schools, and lack of teachers in the schools, the use of negative behavioral methods like suspensions have been up and down. According to a report by Public Funds Public Schools, New York has been underfunding their public schools since 2003, creating “one of the most inequitable school funding systems in the nation,” according to EdTrust New York. However, IDEA funding has been increased by the city to $13 million, bringing its revenue to $304 million, according to a report from State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli.

Although funding for New York City public schools has been on the rise, lack of individuals wanting to work in education and with special needs children continues to create gaps in the school system.

“You have competing interests in careers in New York City. You have people going to law school, nursing, careers that pay way more than being a teacher does,” Adams-Shango said. “It creates shortages in other special education pieces, like behavioral therapists, speech and language pathologists, occupational therapists, and a host of others. These careers are not ones African American students know about unless they’ve experienced it themselves in childhood.”

Faults of the system and schools

Suspension for long periods of time creates negative consequences for a child, especially a special education child. With their brains and bodies signaling different messages to them than another child, it’s hard to keep them regulated and attentive when suspensions are used for discipline.

In 2015, the Solutions Not Suspensions Act, used to reform discipline in NYC schools, was passed to help limit the duration of suspensions and missed class time for students. Although the act was meant to ease the spread of suspensions, the numbers continued to rise, especially among Black and Latino students, who represent an overrepresented and underdiagnosed population when it comes to qualifying for an IEP program, according to 2020–2021 school year data from the Civil Rights Data Collection.

Dominic Buchmiller, a New York City special education attorney, said information about what an IEP entails for the student can get lost in translation, leaving parents confused and searching for more answers — and more suspensions have not helped. He supports using early childhood diagnosis to help create more in-school and outside-of-school support for special needs children.

“Early evaluations that are comprehensive are incredibly important for a student to get access for what they need to make progress,” Buchmiller said. “The families can self-identify a need … but the school district also has an obligation to identify students [who] need special education services. It’s called the initial referral.”

To qualify for an IEP in NYC, according to District 75 NYC, a child must have one of 13 specific disabilities labeled under IDEA and show that the disability has a negative impact on their education. While the process seems easy-going, parents often reach out for outside school support for their children.

“I represent families who have kids with learning disabilities, and they’re not happy with the classroom,” Buchmiller said. “I will work with the parents who disagree with the IEP that the DOE creates for the student and then file a complaint … and try to get the support the New York City Department of Education [should provide] …”

Chief of Special Education Suzanne Sanchez said her main goal is overseeing the education of New York City students with IEPs, making sure they acquire quality services with outcomes that will continue to enhance their education.

The way teachers and staff approach and speak to children, especially special needs children, is important. Sanchez said that trying to approach all students in the same way leads to disconnects, having students with special needs feel left out or behind their classmates, and creating uncomfortable feelings about school. Sanchez also said that the people behind the scenes in different educational departments all have to be on the same page to keep children at the center.

“Not all children learn the same way, so how we teach and how we approach reaching goals for those students matters,” Sanchez said. “Schools use different skills; imagine a child transferring between those schools and learning two different ways. It’s difficult and not what they deserve, therefore we have to get on the same page.”

Reworking the system for a better future

The work of advocacy and transparency is never done in families who have special education children. The state of New York is home to about 382,658 special education students who make up around 15% of the total student population. Among those students, NYC hosts about 200,000 of them. According to New York State Education Department data, special education parents did not report that the schools their children attended during the 2020–2021 school year facilitated parental involvement to help improve services their children were receiving.

Skylar, one of Morris’s twins, began to have aggressive tantrums that became challenging to overcome and hard for the school to manage because she became aggressive. A disturbing way they dealt with it was to place Skylar in a dark tent all day to help manage her outbursts. Instead of working with her and learning who she was as a child learner and a person, they kept her in that dark tent while the class kept learning, resulting in the mother having to remove her from the school.

“Instead of trying to calm her down or have her learn deep breathing and things that I did at home that I knew would regulate and calm her, they placed her in a tent all day,” Morris said. “It was hard to see. She was not getting the education she deserved or needed in order to thrive.”

Morris spent a lot of time in phone and face-to-face meetings, trying to communicate and get the schools to understand methods to help her children thrive in school. She said it seemed as if they understood when she was there, but when she was not, it was a completely different experience, resulting in her having to do surprise pop-up visits to check on her children.

“I don’t think they wanted to take the time to do what I asked. Even when I did pop-up visits to see how they were reacting in certain situations, I still had to get in there and show them hands-on,” Morris said. “The communication was way off. Even though they wrote things down and took notes, they didn’t do what I asked.”

Communication plays a huge role in managing childhood education, especially when a child is special needs or requires additional help. Resources like Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support (PBIS) can be used to help redirect special needs children from receiving harsh punishments stemming from their disability, according to Kent McIntosh, professor of special education at the University of Oregon and a member of PBIS who helps focus on how schools can be made better for the students and educators who attend them.

Kent McIntosh. (Credit: Courtesy Kent McIntosh)

Kent McIntosh. (Credit: Courtesy Kent McIntosh)

“The work that we do leans on these essential elements of this system-level framework … it is something freely available and includes systems, practices, data, all of which is geared toward outcomes and holds equity at the center of what we do,” McIntosh said. “Our work is to provide free support and resources for educators, states, schools and districts, and individual teachers.”

As a father of a child who has special needs, McIntosh said stereotyping students into categories can be separating and installing principles into the school itself versus specific classrooms can help create a better host environment overall.

“Instead of taking kids out of their classrooms and trying to teach them separately, it’s about how do we make the school itself a better host environment for everybody,” McIntosh said. “If we provide something good for every student, then all of a sudden, it becomes clearer and easier for students to know what they’re supposed to be doing, to work with each other, to internalize respect; just ways to manage and thrive.”

The PBIS website has a host of free resources for community members, advocates, families, and schools to implement into their curriculums. Topics range from Bullying Prevention to Crisis Recovery — PBIS covers the foundation so teachers can fit appropriate topics into their daily work. The organization even hosts schools internationally, recently doing a report from a middle school in Japan using Tier 1 of PBIS, which led to strong improvements in the learning and culture of that school.

Sanchez and her team at NYC DOE are dedicated to continuous research and creating weekly digest news for communities to view to stay up to date with notices and priorities. From office hours with superintendents to a new initiative for the 2025–2026 school year called “Inclusion Innovators,” the team is pushing up the ladder for special education representation and workflow.

“In Inclusion Innovators, our center is working directly with six different school districts in New York City, and we are bringing onsite coaching and professional development to their professionals on all things [related to] special education,” Sanchez said. “The goal here is to build that muscle and build that capacity locally at the districts, so that any student who walks into a community school feels not only ready, but resourced.”

In some cases, relocation is best. When Enjoli took action and decided to remove her children from District 75 public schools to a private school, she saw a complete turnaround in her daughters. They began to speak, self-regulate, and even enjoy going to school.

“The environment is completely different and their reactions are completely different,” Morris said. “They’re thriving. They’re speaking. They get on the bus. The school they are at now has meetings more often and communicates better, which makes it easier for everyone to be on the same page and work with the child as one, not as separate entities.”

PBIS has a list of resources and guidebooks for teaching certain curriculums for special needs children and how to manage behavior and discipline. Creating and maintaining equity by viewing students as people first will allow the change of discipline to flow and encourage more participation from students and their families.

“I am 100% confident that my children are now going in the right direction — I can see the difference. If they were in the District 75 school, I’m not too sure how far they would’ve come,” Morris said. “They were able to be met where they were and expanded from that to now being able to communicate and calm down on their own. It was a necessary change not just for me, but for them.”

Jada Vasser served as the Amsterdam News’ 2025 Ida B. Wells Society intern.

Like this:

Like Loading…

Related