HUNT VALLEY, Md. (TNND) — President Donald Trump says he wants to bring back “insane asylums” as part of his effort to crack down on what he refers to as “vagrancy” in big cities in the United States.

He mused that he would reopen insane asylums in a recent interview with the Daily Caller, referencing Creedmoor Psychiatric Hospital and Bellevue Hospital in New York City.

“Well, they used to have [insane asylums], and you never saw people like we had, you know, they used to have them,” he said. “And what happened is states like New York and California that had them, New York had a lot of them, they released them all into society because they couldn’t afford it. You know, it’s massively expensive.”

It’s unclear exactly what Trump means by “insane asylums” and what he means about “reopening” them – considering Creedmoor is still open, and Bellevue closed its psychiatric ward but still accepts mental health inpatients.

But he’s likely referring to psychiatric institutions where mentally ill people could be involuntarily committed for months or years, as a way to combat homelessness, open-air drug use and street crime.

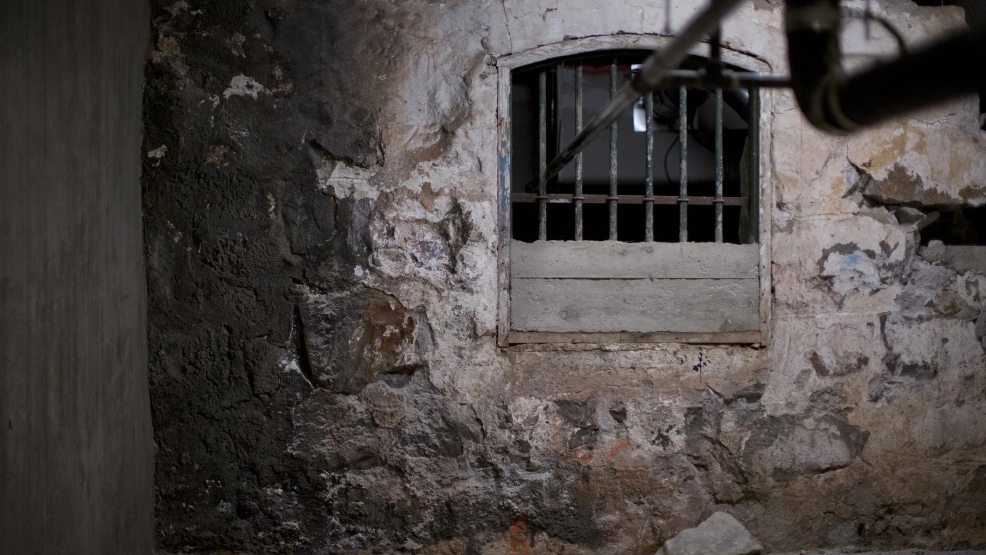

The idea dates back many centuries, perhaps most notably 13th-century “Bedlam” in London, formally known as Bethlem Hospital, which is often associated with inhumane conditions and paranormal legends. There are many abandoned asylums around the world that have become tourist attractions.

In the olden days, society generally viewed mental illness as being caused by a moral or spiritual failing, not a chemical or biological imbalance or byproduct of substance abuse. In the Middle Ages, people suffering from mental illnesses were largely cared for by their families.

But facilities to institutionalize patients actually existed in the U.S. and Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries to care for individuals who seemed too violent or disruptive to remain at home or be cared for by their communities.

By the 1870s, nearly all states had one or more asylums funded by state tax dollars.

These were the days of lobotomies, straitjackets and padded rooms, which actually lasted into the opening decades of the 20th century.

But over time, society developed a different approach to mental health care – “moral treatment,” which was built on the idea that those suffering from mental illness could recover and be cured if they were isolated and part of a system of rewarded behavior.

But the cost quickly added up, and the approach of “moral treatment” didn’t work for all patients. The asylums turned into a catch-all for everything from schizophrenia to dementia to epilepsy.

Then came the economic crisis in the 1930s and World War II, which resulted in shortages of personnel, but no shortages in patients needing treatment.

The ‘50s and ‘60s really marked the peak and then demise of psychiatric institutions as the ancients imagined them.

At their height, in 1955, state-run psychiatric hospitals institutionalized roughly 558,922 Americans.

There were numerous abuse and mistreatment scandals.

“Bedlam 1946” and many other exposés revealed overcrowding, staff shortages, dilapidation of facilities, patient beatings and even murders, harsh restraints, underfeeding, constant drugging and neglect at many of the nation’s largest psychiatric asylums.

Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson kicked off deinstitutionalization with legislation – the Community Mental Health Act, which funded community-based treatment facilities instead of institutions, and Medicaid, which made payments to asylums ineligible for federal reimbursement.

Deinstitutionalization was bipartisan at this point.

State-level conservatives wanted to shift as much of the cost of health care to federal government programs. Involuntary commitment also wasn’t cheap, and they opposed the lack of personal freedom involved.

Meanwhile, liberals condemned the widespread abuse and poor conditions, along with the huge waiting lists for commitment.

And the ethical debate over involuntary commitment began to swirl.

Advocates had long decried the practice, and revelations about overcrowding and poor treatment led them to call it state-sanctioned violence. Proponents still argued the state was maintaining public safety.

When Ronald Reagan was California’s governor in 1967, he signed legislation limiting the circumstances under which people could be involuntarily committed. That decision likely had more to do with money than ethical opposition to the practice.

The Supreme Court eventually waded into the issue.

Three cases in the ‘70s – O’Connor v. Donaldson (1975), Addington v. Texas (1979) and Parham v. J.R. (1979) – essentially established that if someone is not posing a danger to themselves or others and is capable of living without supervision, they can’t be committed to a facility against their will.

According to Politifact, from 1955 to the 2010s, resident populations at state and county psychiatric institutions fell by 93% – from more than half a million to about 37,000.

Most who were deinstitutionalized were severely mentally ill.

More than half were diagnosed with schizophrenia; 10-15% were diagnosed with manic-depressive illness and severe depression; 10-15% were diagnosed with organic brain diseases like epilepsy, strokes, Alzheimer’s and brain damage from trauma; and the rest either had psychiatric disorders of childhood like autism or psychosis or alcoholism and drug addiction with concurrent brain damage.

At the time of deinstitutionalization, the various forms of brain dysfunction and how to treat them was not well understood.

So, where did all these patients go?

Essentially, back into the community, which was the goal of the Community Mental Health Act Kennedy signed. But the law failed to provide enough funding for the number of community health centers lawmakers had envisioned. Congress left the issue to the states, so only about half of the centers were built, and they were still underfunded.

Plus, in the 80s, when Reagan became president, he signed a budget bill that repealed roughly a third of community health funding.

So, instead of having an alternative to an asylum, many of the deinstitutionalized individuals ended up in jail or prison or on the streets.

Incarceration levels skyrocketed. In 1973, the U.S. incarcerated adults at a rate of 161 per 100,000 adults. By 2007, that quintupled to 767 per 100,000. Though other factors could have been at play, like “tough-on-crime” policies.

Homelessness has also increased significantly since the mid-20th century. It’s hard to know how much the homelessness rate may have increased as a result of deinstitutionalization, but studies from the late 80s indicate that a third to half of homeless people had severe psychiatric disorders. Though again, other factors were at play, like housing costs and drugs.

Today, psychiatric care is offered through a variety of different programs: crisis services, short-term acute psychiatric care units at hospitals, and outpatient services that include 24-hour assisted living or various psychotherapeutic treatments.

Nursing homes were developed as a way to care for vulnerable elders; detox and rehabilitation facilities were put up for those struggling with substance abuse; and technology allowed for new medicine to treat severe psychiatric symptoms.

But there is a critical shortage of behavioral health providers. Mental and behavioral health conditions and substance abuse disorders have been increasing for years, exacerbated by the pandemic lockdowns and social isolation.

Several government reports say large caseloads, burnout and confusing or costly credentialing processes are the main factors in the shortage. In 2022, there was only one mental health care provider for every 350 Americans.

And, because of the Supreme Court’s precedent, pretty much all treatment is voluntary, so people have to want it.

As UC San Diego sociologist Neil Gong wrote in his new book called Sons, Daughters, and Sidewalk Psychotics, “With hindsight, the triumph of deinstitutionalization looks more like a tragic irony: an unlikely coalition of civil libertarian liberals and fiscal conservatives pushed for the destruction of an abusive and neglectful system that had nonetheless housed, fed and organized the lives of over half a million people.”

He muses that the pendulum could be swinging back to a less humane approach thanks to the out-of-control homelessness plaguing U.S. cities. It’s at a record high – with more than 770,000 people experiencing homelessness on a single night last year.

That doesn’t necessarily mean lobotomies and conditions like Ken Kesey’s 1962 One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

For one, Trump couldn’t singlehandedly reinstitutionalize America’s mentally ill. It’s a state issue, so while he has a good amount of sway among red states, blue states could fight back against anything deemed particularly draconian.

For two, there doesn’t appear to be physical locations to do so. Homeless shelters and hospitals have long had limited bed space and have to turn folks away, and they don’t have nearly enough resources for an asylum-style setup.

Experts say it’s really only a massive investment that could push states to put up facilities and hire the adequate numbers of mental health professionals and security guards. And it would have to be scalable based on severity of mental illnesses – housing with varying degrees of supervision and facilities with a full range of services, accompanied by revised laws for involuntary commitment only in the most severe of cases.

With an administration trying to cut spending, it’s unclear if there’s a political appetite for such an operation.