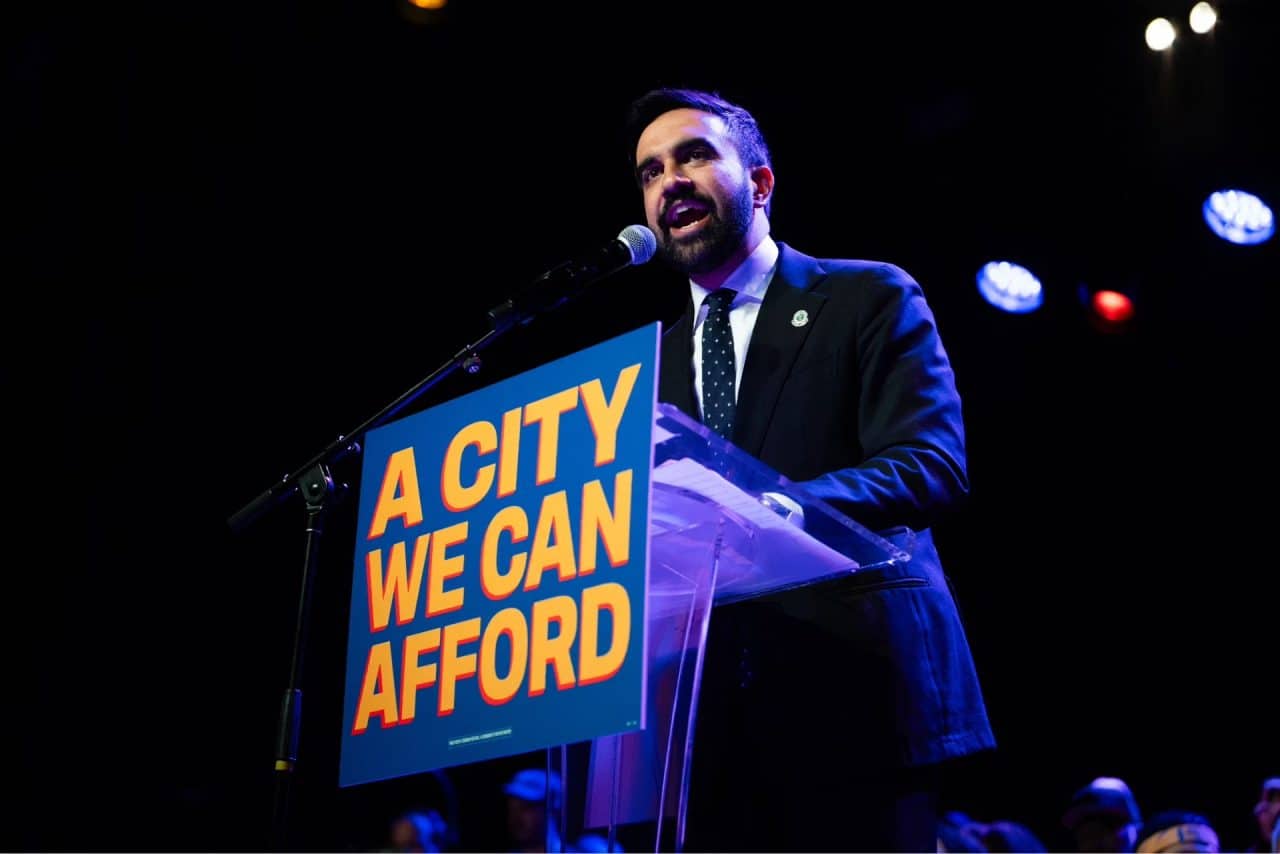

Zohran Mamdani, in condemning Israel’s genocide in Gaza and its Zionist principles while running for New York City mayor, in objecting to “any state that has a hierarchy of citizenship on the basis of religion or anything else,” embodies an intercultural NYC tradition that goes back over a century in NYC. In the wake of Great Britain’s 1917 Balfour Declaration that opened the doors for a Jewish nation in Palestine, Zionism animated debate among not only the 1,600,000 Jewish New Yorkers but also among the almost 5,000 NYC residents of Middle Eastern/Arabic-speaking heritage. Strident anti-Zionist opposition emerged from both of these mostly immigrant communities, articulated in language that remains resonant today.

At the time, NYC’s Arabophone population clustered around the twin poles of Washington Street in Manhattan, known as the “Syrian Colony,” and the “South Ferry” neighborhood at the western end of Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. Living and working in these areas were immigrants and first-generation US citizens from what was then called “Ottoman Syria”—today’s Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Palestine/Israel. The community supported numerous Arab-language newspapers and journals, multiple record labels devoted to Middle Eastern musical lineages, and was home to the Pen League of Arab American writers, including luminaries such as poet/artist Khalil Gibran and novelist/essayist Ameen Rihani.

This intellectual incubator produced, in 1917, the Palestine Anti-Zionism Society, sometimes called the Palestinian League for the Resistance of Zionism. Its first president was writer/translator Nejib A. Katibah, though its prime mover seems to have been physician Fou’ad Shatara. The Palestine-born Shatara had arrived in NYC in 1914, twenty-two years old, fleeing conscription in the Ottoman army. He graduated from Columbia medical school and became a member of the elite New York Society of Surgeons and a teacher at the School of Medicine at Long Island College Hospital and then Cumberland Hospital. Shatara later founded the Palestinian Renaissance Society and became president of the Arab National League of America.

In 1918 and 1919, Shatara made a series of appearances publicly protesting the idea of a Zionist takeover of Palestine. At the Bossert Hotel and the Masonic Temple in Brooklyn, at a meeting in Bernardsville, N.J., he spoke alongside, variously, Katibah, Rihani, and Columbia professor Philip Hitti–now considered the originator of Arabic Studies in the US. Some of these events were under the auspices of the Palestine Anti-Zionism Society; others were not registered as such by the English-language newspapers, which did, however, report Shatara’s speeches: “We protest against the usurpation of the homes and property of a people, weakened and impoverished by centuries of misery… [and against] artificial importation of Zionists flooding the country.”

The events drew criticism, and accusations of anti-Semitism which Shatara addressed in a letter to the Brooklyn Citizen in December of 1918:

The Syrians harbor no hatred toward the Jews. On the contrary. we fully sympathize with the aspirations of the Jews throughout the world, and with their efforts to solve the “Jewish problem,” but we feel that giving Palestine to the Zionists, far from solving the Jewish problem, will add to it greater problems by instigating feuds and contentions in a country which has been the hotbed of religious disputes, and which is sorely in need of peace. The Syrians, not being in any way responsible for the Jewish problem, should not, in an attempt to solve that problem, be punished by forfeiting Palestine, a province of Syria.

The Palestine Anti-Zionism Society had been founded on the belief that the US should and would advocate for self-determination in Palestine, building on the allied WWI victory in the region. In 1920, headquartered at 396 Broadway on Canal Street, the Society was in contact with the US State Department, pleading for the US to consider Zionism’s potential to devastate the population of Palestine: “Palestinians at home and abroad look to the United States for justice.”

In 1921, now renamed the Palestinian National League and located in the heart of the Syrian Colony, 85 Washington Street, the organization published The Case Against Zionism, a slim volume of enormous power. It was edited by H.I. Katibah, then twenty-nine years old, who was born in Syria to a Muslim family and had come to the US to study at Harvard. He would become a regular contributor to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, coeditor of The Syrian World, an internationally respected expert on Middle Eastern politics. In the forty-some prescient pages of The Case Against Zionism, Katibah predicted a rise in anti-Semitism spurred by Zionism: “If the Jews want a national home in which their national life and culture will have an untrammeled development, Palestine is not the place for them. If they are fleeing to Palestine from persecution and Anti-Semitism, they will find that persecution will meet them in intensified and bitter form in Palestine, and Anti-Semitism in the whole world will revive and become more entrenched than ever before. This is actually taking shape before our eyes.” Rihani, too, penned sharp warnings, about a Zionist state and its colonial underpinnings: “Zionism, with the British mandate as a shield and money as a weapon, is another form of conquest.” He preferred envisioning a multi-ethnic Palestine overseen by “a representative government in which the Jews that are now in the country shall enjoy equal rights with the Arabs.”

In 1922, Republican Senators Henry Cabot Lodge, Massachusetts, and Charles Curtis, Kansas, and Representative Hamilton Fish, Jr., New York, were introducing a resolution of support for the Balfour Declaration. These three, all anti-immigrant, were not obvious allies of marginalized peoples such as Jewish Americans of the time; Lodge in particular was a known anti-Semite, and Fish flashed signs of it. Their committee called on Shatara to testify about the potential injustices of making Palestine the site of a Jewish nation. Shatara pointed out that less than 15 percent of Palestinians were Jewish, and that imposing a Jewish state on the region’s inhabitants would go against the principle of self-determination espoused by the League of Nations. Also taking the stand was Rabbi Isaac Landman, editor of the weekly The Hebrew and Jewish Messenger, who excoriated the Zionist movement, asserting it was much less popular among US Jews than assumed, and largely driven by political elites and their agendas. Landman argued that a Zionist state would create unjust hierarchies among Jewish people, that Zionism served to exclude “those Jews who are opposed to Jewish nationalism.” (Is it too much to call him the Brad Lander of his day?) He did not object to Jewish migration to Palestine, he said, just to the goal of creating a Jewish state. His testimony irked a few members of his congregation, Temple Israel of Far Rockaway, Queens, housed at 88 Beach 84th Street, who tried having him removed–and failed, testimonial to the appeal of his views.

Landman, also an immigrant, a victim of land theft, had arrived from Russia in 1890, aged ten. During an eccentric, checkered career, he founded a farming colony of two hundred Jewish families in Clarion, Utah in 1911, and, during WWI, served as chaplain in the US military in Mexico and Europe. A forceful opponent of anti-Semitism, he challenged Henry Ford to public debates and denounced the KKK, leading to the epithet, “the two-fisted rabbi.”

He is perhaps best known today for authoring the Universal Jewish Encyclopedia.

In 1921, Landman created a forum in the Messenger about plans for Great Britain’s Palestinian Mandate, inviting prominent Jewish thinkers such as Rabbi Stephen Wise, a staunch Zionist, to contribute. (Wise declined.) Landman represented a sizable anti-Zionist movement among Jewish New Yorkers. When the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, an association of Reform synagogues, held a four-day convention in January 1923 at the Hotel Astor, it kept out all mention of Zionism. The National Council of Jewish Women Organization, led by Brooklyn native Rose Brenner, resisted pressure to incorporate Zionism from, for example, Henrietta Szold and Hadassah. NYC novelist Fannie Hurst was a prominent Jewish figure who spoke out against Zionism, a movement that she thought “segregates us, raises barriers or creates race prejudice.” These leaders in NYC’s Jewish community heeded the racist implications of synthesizing a Jewish nation where non-Jews were already building a state. Landman, in particular, recognized that the real threat to Jewishness, in the US, in the world, comes not from Jewish support for Palestinian sovereignty but from US white supremacy–about which Lander and Mamdani are still sounding the alarm.

Landman’s life story, alongside those of Shatara, Katibah, Rihani, and others, remind us that Anti-Zionism in the US has long been an intersectional project supported by Arab/Muslim and Jewish immigrant communities, and long prompted morally conscious figures in polyglot New York and everywhere to protest. These figures also show us how diaspora, how a mix of cultural heritages, can shape attitudes on the issue. Rihani, writing in 1921, explained: “I’m Syrian first, Lebanese second, and Maronite third. I am proud of my Arabic language and heritage and the glory of Islam. But I believe in the separation of religion and politics.”

Rihani drew on this background to envision his multi-ethnic ideal of Palestine–as Mamdani today draws on his complex cultural biography; he is a dual citizen of Uganda and the US (naturalized), born into a transnational Indian family now based in New York, a practicing Muslim, a resident of Queens who spent his childhood first in Cape Town and then in Morningside Heights. Mamdani’s opposition to Israel’s slaughter of Palestinians has been shown to match that of much of the NYC population. He has spoken about how the diasporic city is a natural bastion for opposition to Zionist genocide. “New Yorkers have felt betrayed by our politics across this country and across this city… [and] are asking for is an equal application of that humanity, no matter who it is that is under attack.” Mamdani’s forebears in NYC a hundred years ago asked for the same.