LANSING, MI — The state of Michigan began testing a random assortment of rivers and streams for microplastics this year. Data from the first sampling round is being analyzed and quality-checked, but the preliminary results are not encouraging.

Basically, they’re finding it everywhere.

“From an initial glance, I guess you could say that microplastics were pretty ubiquitous across our samples,” said Eddie Kostelnik, an analyst in the emerging pollutions section at the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE).

“It didn’t necessarily matter whether that stream was in a remote area, like in the U.P., or a more urban area or in an agricultural impacted area,” he said. “We’re seeing microplastics across most of the rivers and streams that we’ve sampled so far.”

In May, EGLE took its first stab at understanding the prevalence of microplastic in the state’s environment. Using a one-time $2 million appropriation in its fiscal 2025 budget, the agency will test 200 rivers and streams around Michigan between now and 2029.

The agency’s increasing attention on microplastic comes amid mounting global concern with the ecological and public health risks of the tiny polymer fragments that enter the environment through breakdown of larger products, shedding from synthetic fabrics, intentional additives and leachates that wash through wastewater plants.

Microplastics are also on the radar of Democratic lawmakers in Lansing, who’ve proposed a package of bills that aim to reduce the overall use of some microplastics and better understand their occurrence in Michigan drinking systems and surface waters.

The legislation, which the Senate Natural Resources committee heard testimony on Tuesday, Sept. 9, would build upon EGLE’s nascent sampling effort.

One of the bills, SB 505, would create a Part 151 under the state Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act. It would direct EGLE to develop a strategic statewide research and monitoring plan, establish baseline concentrations in the Great Lakes and contract with academic researchers to assess microplastic occurrence and impacts.

Another bill, SB 504, would establish baseline concentrations in public water supplies and require quarterly monitoring and testing, with a detailed report due in 2031 that includes a recommended toxicity limit and preliminary risk assessment for public water supplies.

A third bill, SB 503, would ban products made with microbeads, a type of tiny plastic added to cosmetic products. The prohibition would close a gap on similar, but more limited existing federal ban on microbeads that only applies to rinse-off products.

“Plastics are not inert and scientists know that they can cause cancer and affect our hormones,” said Democratic Sen. Sue Shink, the committee chair. “By creating a research and monitoring plan, Michigan can effectively respond to this pollutant.”

Democratic Sen. Jeff Irwin of Ann Arbor, a bill sponsor, said the goal is to “get our arms around this problem.”

“I didn’t know about ‘nurdles’ until I started working in this legislation,” Irwin said, suggesting fellow lawmakers look up the word for industrial pre-production pellets that can be found in surprisingly high quantity on Great Lakes beaches.

Republicans on the committee asked questions about potential enforcement and how the legislation might impact agriculture but did not voice opposition. The bills do not currently have any bipartisan sponsors. The legislation drew support from environmental advocacy groups, but opposition in its current state from the chemical industry.

Marcus Branstad of the American Chemistry Council took issue with provisions that limit research partners to academic institutions, called the definition of microplastics “overly broad” and characterized timelines for implementation as too ambitious.

“Requiring a safe limit for microplastics by 2031 is premature,” he said. “Standards should be tied to evidence of adverse health effects, not just picking a date six years down the road. Lessons from California show the complexities and costs of statewide monitoring.”

Donna Kashian, an environmental science professor at Wayne State University who leads the International Association of Great Lakes Research and serves on the International Joint Commission (IJC)’s Great Lakes Science Advisory Board, said new research is coming out monthly on the negative health effects of microplastics on humans and animals.

In November, the IJC released a report that found microplastics to be “ubiquitous” across water, sediment, biota and beaches in the Great Lakes basin. The report noted evidence of microplastic in Great Lakes drinking water sources and fish and found that some ambient water samples show concentrations that exceed existing risk thresholds.

More: Plastic pollution is worsening in the Great Lakes

The report urged harmonization of research and monitoring methods across governments and suggested designating microplastics as a chemical of mutual concern by the U.S. and Canadian governments.

In lakes and rivers, microplastics pose a risk to humans who eat fish because, “plastics act like little carbon particles and they will attach to other contaminants like metals, PCBs and PFAS,” Kashian said. “When an organism goes to eat them, they’re getting a more clustered amount of these chemicals — a concentrated amount that they’re ingesting.”

Elin Warn Betanzo, a former federal drinking water engineer and private consultant who played a pivotal role in helping expose the Flint water crisis, urged lawmakers to require water sampling at customer taps, not just at the water treatment plant.

“Tap water monitoring is essential — especially in communities with plastic water mains, plastic service lines and plastic plumbing,” she said. “Sources of microplastics in our drinking water after the water leaves the treatment plant may include polyethylene PVC, HDPE and PEX pipes that are becoming more and more popular.”

“We need to know not only what is in our source water and what passes through our water treatment plants, but also what contaminants may increase once water travels through plastic pipes to residence taps,” Betanzo said.

In the meantime, EGLE’s sampling effort is collecting a second round of water samples this month and will grab a third in November.

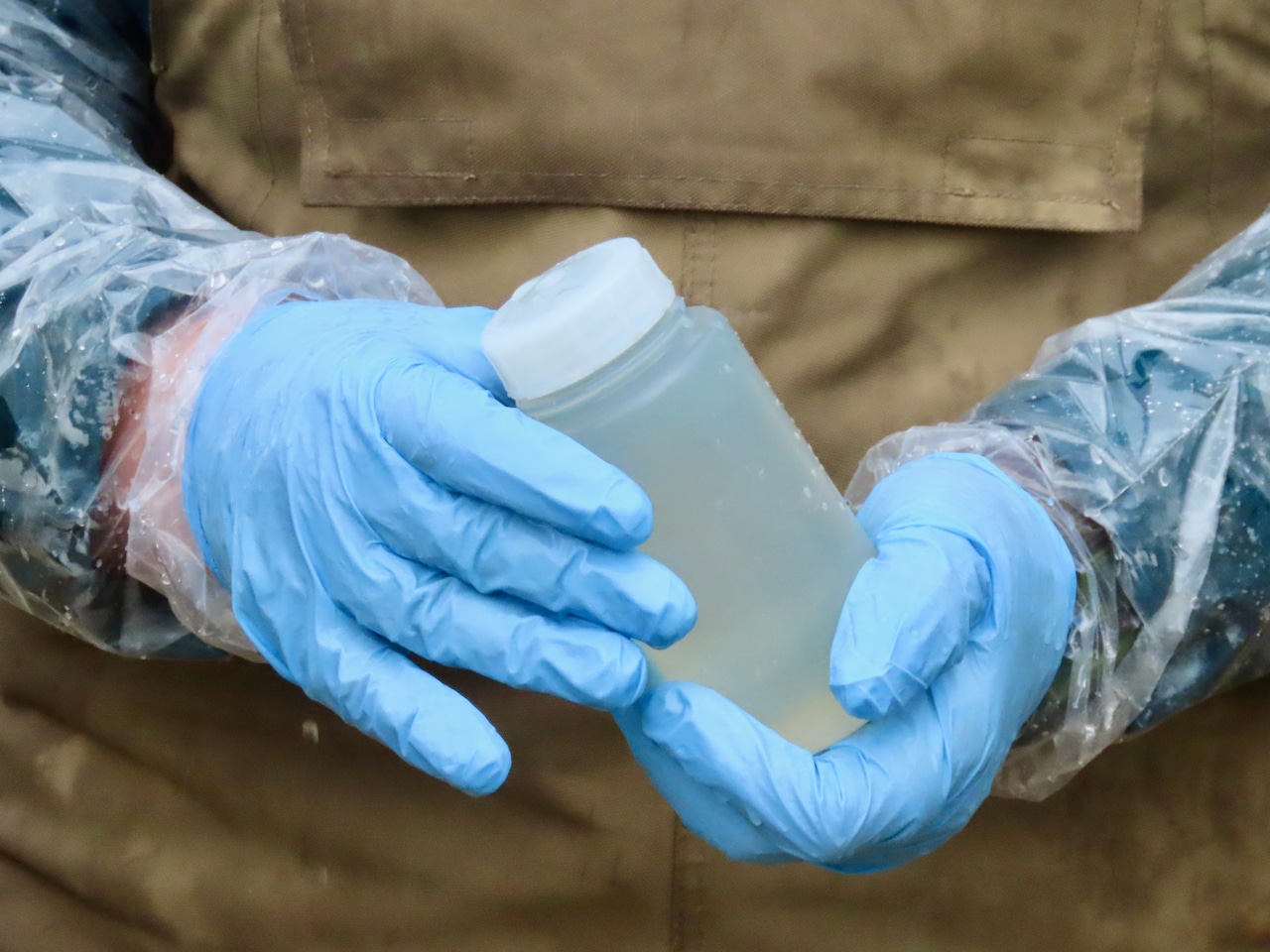

Megan Nakoneczny, a field researcher with Great Lakes Environmental Center (GLEC) takes water chemistry samples near Nashville, Mich., July 9, 2025. The stream was being tested for a variety of contaminates through the Michigan EGLE water chemistry monitoring program.Garret Ellison

Megan Nakoneczny, a field researcher with Great Lakes Environmental Center (GLEC) takes water chemistry samples near Nashville, Mich., July 9, 2025. The stream was being tested for a variety of contaminates through the Michigan EGLE water chemistry monitoring program.Garret Ellison

The agency folded microplastics to an existing water chemistry monitoring program that grabs water samples from 50 randomly selected sites three times a year and analyses them for a variety of contaminants, including pesticides and PFAS.

Kostelnik said EGLE is already working across divisions and programs to develop a more holistic strategy around microplastics. The agency is looking at procedures developed in California, as well as strategies developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

“But there’s not a ton of information out there at this point,” he said. “There is going to be a good amount of building of what’s best for Michigan and the waters of the state.”

If you purchase a product or register for an account through a link on our site, we may receive compensation. By using this site, you consent to our User Agreement and agree that your clicks, interactions, and personal information may be collected, recorded, and/or stored by us and social media and other third-party partners in accordance with our Privacy Policy.