As San Antonio copes with its deadliest flood year in more than three decades, local leaders eager to move toward solutions are finding the issue in tough competition with flashier development projects.

Speaking to residents at Lion’s Field Senior Center this month, Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones warned that the city’s financial analysts are projecting the next infrastructure bond could be much smaller due to slowed economic growth — roughly $500 million compared to the $1.2 billion bond the city approved in 2022.

That’s as city leaders are already counting on a large share of that money covering streets, roads and other infrastructure related to the downtown sports and entertainment district known as Project Marvel.

“We’ve got to be clear-eyed about the changes in our budget, but also the big investments that we as a community want to make together,” Jones said to a room of roughly 200 attendees — her voice raised to be heard over fans masking a broken HVAC system at the senior center.

“We care about infrastructure. We certainly care about the floods. … We also care about making sure we’re supporting downtown development,” Jones said. “But what’s the right balance?”

Jones’ mayoral tenure began just a day after San Antonio and Bexar County issued a joint disaster declaration seeking state assistance for deadly floods on June 13 that left 13 people dead on the Northeast side.

Newly sworn-in Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones gives her condolences to the families of the victims of the flooding off Perin Beitel and Loop 410. Credit: Vincent Reyna for the San Antonio Report

Newly sworn-in Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones gives her condolences to the families of the victims of the flooding off Perin Beitel and Loop 410. Credit: Vincent Reyna for the San Antonio Report

As of this week, however, city spokesman Brian Chasnoff said San Antonio hasn’t received any state or federal funding for the recovery efforts.

The city directed $12.5 million in the fiscal year 2026 budget that council approved Thursday for “debris clearance and emergency repairs” at the three low water crossings affected by the June flood.

Against that backdrop, Jones has been touring local sites that topped the state’s list of its most pressing flood control projects — but which haven’t received state money.

Special sessions in the Texas Legislature put funding toward disaster relief and warning systems particularly in the Hill Country after devastating summer floods, but didn’t unlock any additional money for flood control projects.

SAFD officials wade into a creek near Perrin Beitel Bridge after severe flooding that swept motorists into the flood water in June. Credit: Blaine Young for the San Antonio Report

SAFD officials wade into a creek near Perrin Beitel Bridge after severe flooding that swept motorists into the flood water in June. Credit: Blaine Young for the San Antonio Report

That’s after Bexar County was skipped over completely in the first round of the state’s Flood Infrastructure Fund — due in part to the region’s already advanced investments in water management studies.

“On the state’s flood mitigation plan, San Antonio has 14 projects that would cost us $411 million if we wanted to pay [for it ourselves],” Jones said at the Sept. 4 town hall.

“We have to be thoughtful about, what do we care about?” she added. “Because, all of a sudden, that $500 million [in bond capacity], goes by real quick.”

Bexar County’s pivot to basics

Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai faces a similar challenge.

He campaigned for county judge vowing to refocus county spending on more basic needs — an idea that was only reinvigorated by the Hill Country flooding that left hundreds dead over the Fourth of July weekend.

“The review [of Kerr County officials’ flood response] has been quite brutal,” Sakai said at an Aug. 12 Commissioners Court meeting. “It has reminded me what my primary job as county judge is, and that’s to protect this county.”

Though Sakai remains adamant about moving away from the sorts of large-scale development projects favored by his predecessor Nelson Wolff, the pivot has been somewhat slow-going.

Like the city, Bexar County requested money from the state in response to the June flooding, and budgeted $22 million for an automated countywide flood gate system it hopes the state will eventually pay the county back for.

Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai speaks about the federal Westside Creeks Ecosystem Restoration Project in January. Credit: Brenda Bazán / San Antonio Report

Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai speaks about the federal Westside Creeks Ecosystem Restoration Project in January. Credit: Brenda Bazán / San Antonio Report

But at a budget town hall on the West Side last month, residents were more concerned about the infrastructure projects that prevent flooding in the first place, which they said have become less focused on residential needs in recent years.

Bexar County is solidly in flash-flood alley, and has invested $1 billion in flood control over the past two decades.

It has a road and flood control line item on its portion of residents’ property tax bill, and in 2007, it used that money to fund a 10-year Flood Control Capital Improvement Program that included projects across the county.

More recently, however, the money has gone toward projects with an economic development focus, like the San Pedro Creek Culture Park.

At the budget town hall, Monticello Park Neighborhood Association President Bianca Maldonado asked when the county would again solicit projects for the whole metroplex, noting her neighborhood is in a 100-year floodplain that’s expected to need $80 million in drainage fixes over eight phases.

“When will the county initiate another regional flood control program?” she asked. “[We need] a plan to improve life safety in my community.”

While county leaders agreed they need to return to a more county-wide approach, commissioners who’ve struggled to see eye-to-eye on major spending priorities have repeatedly delayed tough conversations about their capital budget.

“You’re right, we’ve got to figure out that next round of flood control projects,” Commissioner Justin Rodriguez (Pct. 2) replied to Maldonado. “Hopefully that discussion will be coming soon.”

As the city, county and Spurs move forward on a new downtown arena for the NBA team, Bexar County is also proposing updates to the Frost Bank Center and Freeman Coliseum on the East Side. Credit: Cooper Mock for the San Antonio Report

As the city, county and Spurs move forward on a new downtown arena for the NBA team, Bexar County is also proposing updates to the Frost Bank Center and Freeman Coliseum on the East Side. Credit: Cooper Mock for the San Antonio Report

Other residents at the August budget meeting wanted Bexar County to use the money it plans to put toward a new downtown Spurs arena and East Side rodeo grounds on flood control — citing a previous venue tax election put money toward river projects.

But Sakai said he had little choice on pursuing the Spurs arena and East Side projects.

The team’s owners had already been working with the city on a plan to end its lease at Frost Bank Center before he took office — leaving a major county-owned asset at risk of abandonment.

“When I first ran for county judge, I had no idea that this would be on my plate,” Sakai said. “Once we knew that this was going to happen, we immediately had to figure out, how do we protect the county facilities?”

A slow process

San Antonio’s list of flood control needs is much longer than just the 14 included on the state’s flood plan.

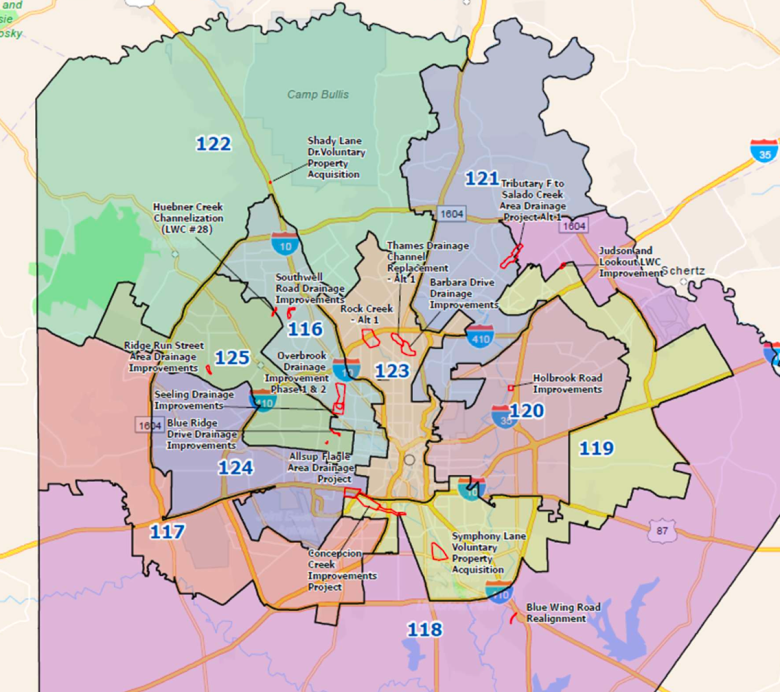

Of those, however, four were ranked in the state’s top 100 priorities: Concepcion Creek on the Southwest Side, Overbrook and Southwell Road drainage improvement on the Northwest Side and Seeling drainage improvements on the West Side.

At a meeting with residents just after the June flooding, state Rep. Trey Martinez Fischer (D-San Antonio) was also peppered with questions about how to make flood infrastructure more of a priority for a state with major budget surpluses in recent years, but seemingly little interest in proactive solutions.

“These folks are reactionary lawmakers,” Martinez Fischer said of his fiscally conservative colleagues. “Every time we bring a scenario to get ahead of something, because we listen to the science, we listen to the experts. … These folks in the mañana caucus don’t want to [spend the money to] fix it.”

San Antonio flood mitigation projects in the state’s flood plan, divided by state House district. Credit: Courtesy / Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones’ office

San Antonio flood mitigation projects in the state’s flood plan, divided by state House district. Credit: Courtesy / Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones’ office

Martinez Fischer said most flood control projects require major advocacy from the residents who want them, and even then, take many years to assemble the funding.

The city’s project list, for example, includes some projects that have already been budgeted for in a bond election, in hopes that the city could leverage a local match for state dollars to fund another phase.

“I waited tables at my parents’ restaurant off Fredericksburg Road in Five Points, which used to be ground zero for floods in San Antonio,” Martinez Fischer said. “That neighborhood never gave up, if you go [there] today, it’s got tremendous flood control.”

To local leaders’ point, however, he suggested the faster solutions are likely to come from closer to home.

“Obviously, this [summer’s flooding] took everybody by surprise,” he said. “The difference is I see our state leaders defending, deflecting, shifting the blame, wanting to change the subject … I see local leaders saying, ‘We understand, we’re going to move with urgency. We get it.’”