More for families.

If you’re enjoying this article, you’ll love LAist’s early childhood newsletter. Every two weeks, you’ll receive top reads and resources on issues affecting families with kids ages 0–5.

I was in my early 30s when I moved to L.A. in 2000 to start a job as a reporter at then start up all-news KPCC 89.3 (which later became LAist 89.3).

Over the past 25 years I have learned so much as I travelled around the region and talked to so many people.

I have witnessed history and heard people’s joy, aspirations, fears and pain, from Armenians, Cambodians and Jews talking about their own definitions of genocide to the red-carpet inauguration of the Walt Disney Concert Hall.

Los Angeles is the ink I used to write this book: An interview with LAist’s Adolfo Guzman-Lopez

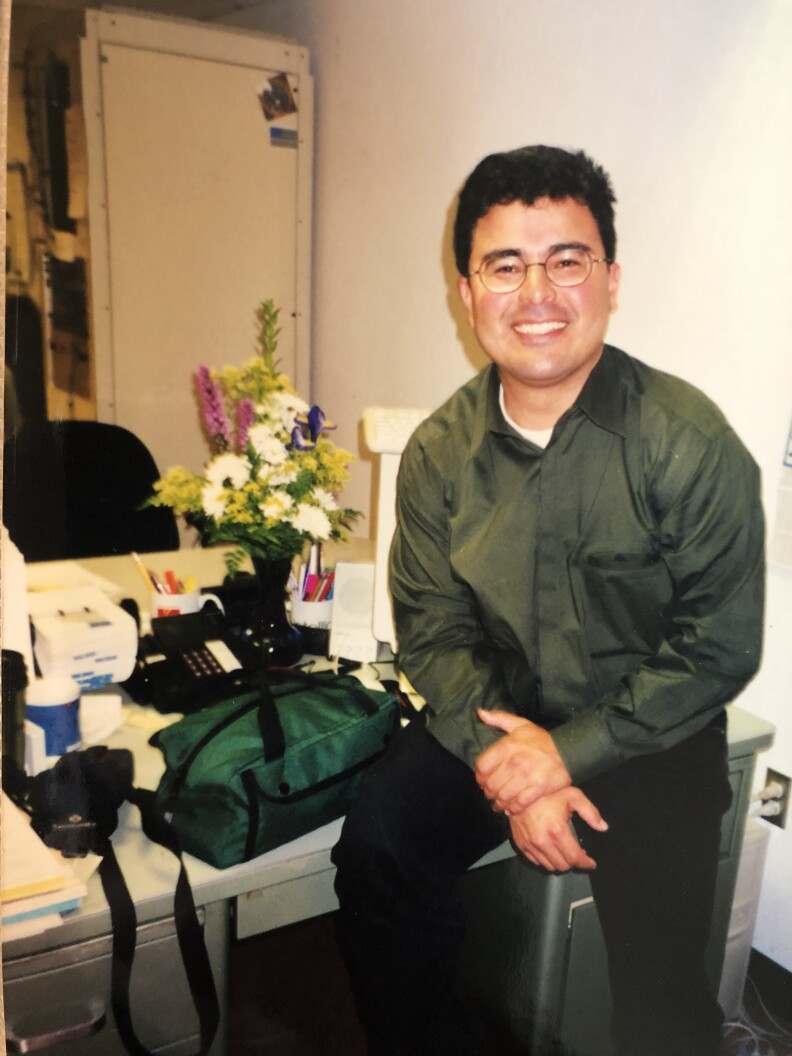

Adolfo Guzman-Lopez performs with the Taco Shop Poets in L.A. in the early 2000s.

(

screenshot from video

/

Adolfo Guzman-Lopez

)

Meanwhile I’ve also had another life for even longer, as a performance poet, co-founding the influential Taco Shop Poets in the 1990s.

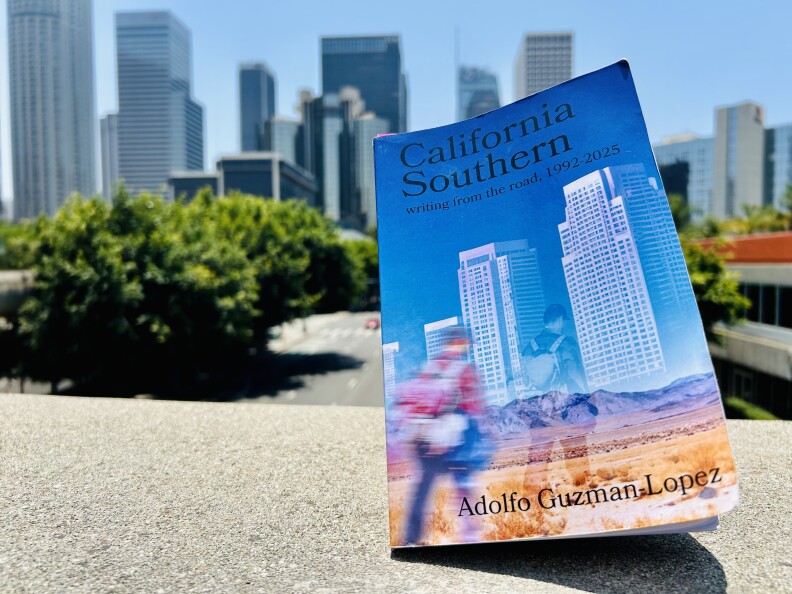

In my first collection of writing, California Southern: writing from the road, 1992-2025, I’ve attempted to capture both sides of myself.

California Southern: writing from the road, 1992-2025 is the first collection of writing by LAist correspondent Adolfo Guzman-Lopez

(

Adolfo Guzman-Lopez/LAist

)

In poetry and prose, I’ve tried to describe the feelings of returning to a Mexico that I only spent some of my childhood in, while meeting people, Mexican and not, who share stories about leaving a homeland and trying to find home in Southern California.

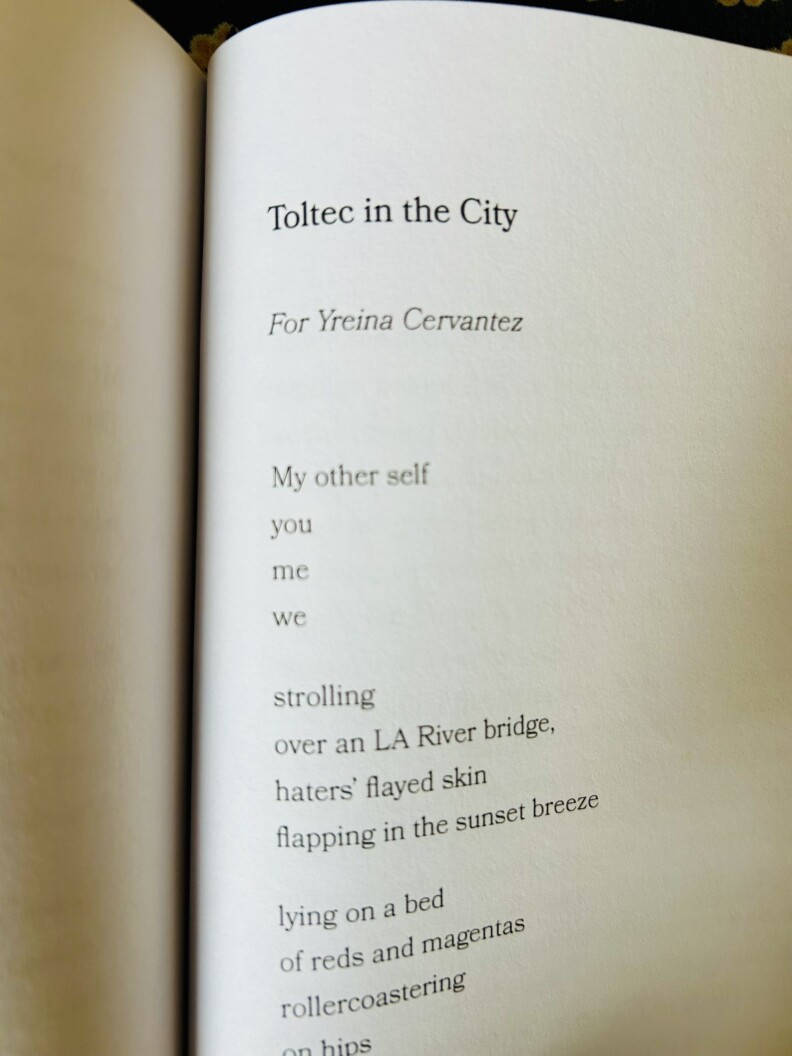

The poem Toltec in the City in the book, California Southern: writing from the road, 1992-2025

For example, the poem near the book’s beginning, Vine a Los Angeles (I came to Los Angeles) melds the Aztec origin myth I learned as a child with a description of the many varied layers of history I discovered in L.A.

The eagle

perched on the cactus

called me to Los Angeles.

The Templo Mayor lays buried here.

In my city,

Mexico City,

jaguar heads of volcanic stone

became cornerstones for colonial palaces,

became podiums for politicians,

became baptism wells for el nuevo mexicano.

In my new city

adobe forts

became foundations

for post-war tract homes,

as far as the eye can see.

They sway

like Kansas wheat fields.

It’s here,

the Californio city

buried

under the oil well city

buried

under the Zoot Suit city

buried

under the Dunbar city.

Orthodox shuls

under Brooklyn Avenue

sonidero speakers.

The Eastside minaret

blasts narcocorridos.

The Eastside minaret

blasts Cri Cri.

The Eastside minaret

Blasts na-na-na-na-na-na-na-na-na-na-na.

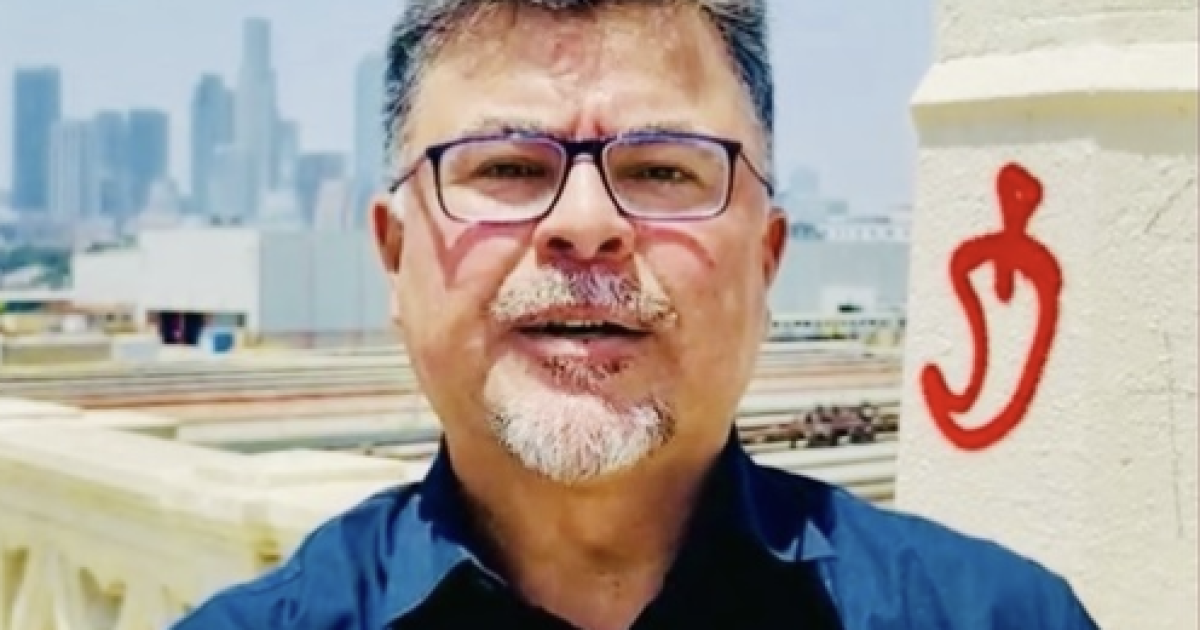

Adolfo Guzman-Lopez interviews California Faculty Association official Margarita Berta-Ávila.

A reporter who is also a poet

As major protests roiled Southern California in recent years, I’ve joined my LAist colleagues to cover them. In 2020, in Long Beach, I was shot by local police at a protest for George Floyd. A foam round hit me in the bottom of my throat. Writing certain sections in the book has helped me process that. Other pieces, like Boom Town National City, capture other traumatic moments that resonate with me.

That piece includes descriptions of a 2018 Border Patrol detention of a woman on a street corner of National City, where I grew up. The woman’s daughters screamed as she was shoved into a van by agents. The screams were captured on video. Those kinds of detentions did not happen frequently at that time. As someone who had been undocumented at about the same age as the girls, their screams and the detention shook me to my core.

Adolfo Guzman-Lopez began working as a reporter for KPCC 89.3 in 2000.

The piece contemplates how writing may help people deeply impacted by these acts come to terms with them.

Fill your fountain pen with blood, fill it with the rainbow ink sliding down the corner of your eye. Write your own postcard. Write it multiple times. Write it when you love. Write it when you’re lonely. Write it when you feel that you’re returning to your original self, your whole self.

Write it when things happen that make you cry.

And wake up!

Helping build a more perfect and harmonious community

The book ends with a poem that includes phrases from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The agreement was signed by Mexico and the U.S. in 1848 and put an end to a war between the two countries. What is remarkable to me is the language in the treaty to protect the civil rights of the Mexicans who now lived in U.S. territory ceded by Mexico. Today, nearly 180 years after that treaty was signed, the language beckons to action, to work towards the peace that the treaty envisions.

In the name of almighty god

animated by a sincere desire

to put an end to the calamities of war

and establish relations of

peace and friendship

benefits upon the citizens of both

Friendship

Limits

And settlement

Without exception of places or persons

I’ll be reading from and signing copies of California Southern: writing from the road, 1992 – 2025 at 3 p.m., Sunday, June 29, at Sonoratown in downtown Long Beach — it’s part of the Los Angeles Design Festival. Tickets are free.