Overview: Protesting on campuses

While deportations were not confirmed, four SDSU students did have their F-1 visas revoked and exchange records deleted, the Office of the President confirmed in an April 10 campuswide email. On April 25, SDSU told news outlets that three of the four visas had been reinstated.

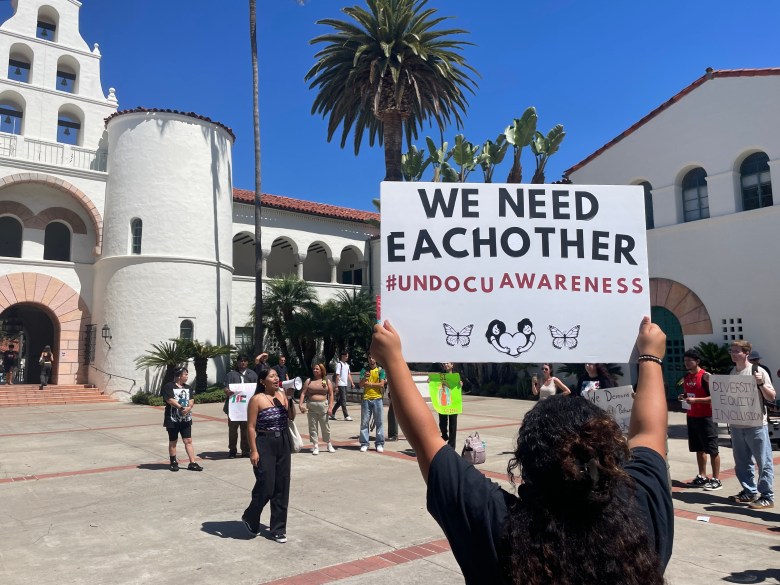

Throughout 2025, university students across San Diego have been exercising their right to protest, most commonly for pro-Palestine and anti-Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

University of California San Diego reports there have been dozens of “free expression events” since October of 2023, with a May 2024 event resulting in 65 arrests.

San Diego City College has seen protests of varying sizes, and San Diego State University has had hundreds of students participating in walkouts and demonstrations throughout the last couple of years.

As a result, many universities, including SDSU and UCSD, have implemented Time, Place and Manner policies that place guidelines on expression forms, but not on protest content.

Many campuses — including SDSU, UCSD, San Diego Community College District and University of San Diego — have also implemented ICE non-compliance policies.

Amid federal funding cuts for universities and President Trump’s threats to freeze funding for any campus that “allows illegal protests,” campuses are feeling the heat.

Top universities across the nation have negotiated with the new administration, implementing new policies and spending allocations that align with federal values to receive their funding.

California is feeling the heat

California as a whole is also feeling the heat, especially after the Sept. 8 Supreme Court ruling that overturned a Los Angeles district judge’s order that blocked ICE from targeting individuals based on ethnicity, language, workplace and location.

On Sept. 10, the Trump administration cut $350 million in grant funding for Hispanic-Serving Institutions, of which SDSU is one of 167 in California.

As a result, many SDSU students said their university is keeping a little too quiet, with some expressing concerns about potential ICE presence.

“I know they say that they’ll stop them from coming on campus, [that] it’s illegal. But, people have said that before and stuff is still happening, so that’s still a concern,” second-year psychology student William Reyes said. “Like I still know it might happen, but I think there are countermeasures for it.”

Reyes said changing immigration policies has impacted his extended family, and he thinks the university could be doing more to support students.

“They do send the emails, but a lot of students don’t really check their emails and even then, the emails that they do send kind of get lost,” he said. “I do remember there was, sometime last year, that there was nine or so students that got deported. And we were never told about that, I had to learn through a professor who shared that story with the class.”

While deportations were not confirmed, four SDSU students did have their F-1 visas revoked and exchange records deleted, the Office of the President confirmed in an April 10 campuswide email. On April 25, SDSU told news outlets that three of the four visas had been reinstated.

Three days prior, at UCSD, five students had their F-1 visas revoked and a sixth was deported. Later that month, the revocation number rose to 35, but all were reactivated shortly after.

Reyes applauded the various student protests that were organized last year, but said he hasn’t been hearing many immigration conversations around campus.

ICE and immigration policy are topics of conversation at school

For fourth-year aerospace engineering student Kiersten Funk, ICE and immigration policy are a big topic of conversation in her classes, friend groups and at her old job.

“A lot of my friends are immigrants. I come from a family of immigrants, so it’s just definitely a topic of concern for everybody,” Funk said. “… ICE is targeting Mexican immigrants. I’m not Mexican myself, but a lot of people do think that I am. And so sometimes, I’m subject to some of the same hostility towards that demographic. So definitely my heart goes out because it does suck.”

Funk admitted she doesn’t pay too much attention to the many university emails, which is the main method SDSU uses to update the community and inform them of their rights, in addition to documents available on its website and staff available at resource centers.

“I can’t say I’ve received too many [emails] informing students on their rights. I’ve heard students informing other students of their rights,” she said. “In the spring, I was hearing student leaders in clubs and such informing their members that they don’t have to answer any questions they don’t want to, they don’t have to answer to ICE if they knock on their door.”

While she wasn’t on campus much in the spring, she applauded the student and local protests.

“I think that it’s great what they’re doing,” she said. “The ones that I’ve seen, they’ve been very peaceful and it’s just a group of people standing up for what they believe in.”

Later that day, the first protest of the new academic year commenced on campus, organized by student advocacy group Movimiento Estudiantil Chicanx de Aztlan, or M.e.Ch.A.

“ADELA, ADELA, HEAR OUR PLEA. YOUR SILENCE IS COMPLICITY,” echoed through campus on Sept. 10.

“Shame on SDSU,” the protest was titled in a social media promotional flyer. The caption of the post read: “… The Supreme Court has deemed racial profiling as a ‘relevant factor’ for ICE agents to stop someone. While SDSU administration may be silent, we the students will not allow our communities to be attacked!!”

M.E.Ch.A. Co-Chair and fourth-year criminal justice student Karla Chaj-Perez said she is unsure why SDSU has not spoken about the recent Supreme Court ruling.

“SDSU has, for the past year, invited Homeland Security, invited ICE to their career fairs, and it makes the students feel unsafe,” Chaj-Perez said in an interview. “Imagine crossing the border every single day, being on that trolley for like two hours, and then you come here to see someone who might detain you. I have a lot of empathy for those students, and wanting to stand up for them and standing with them so that they don’t have to be afraid.”

Karla Chaj-Perez speaks at M.E.Ch.A. protest. (Photo by Calista Stocker/Times of San Diego)

Karla Chaj-Perez speaks at M.E.Ch.A. protest. (Photo by Calista Stocker/Times of San Diego)

A spokesperson for SDSU said ICE has not participated in any recent career fairs, though an FAQ page does state that ICE officials “may be participating in a Career Services related function … It is a mistake to assume that any federal immigration authority visiting campus is present to apprehend or remove a member of the CSU community.”

No stranger to campus protests

Chaj-Perez is no stranger to hosting and participating in campus protests — and no stranger to SDSU reaching out once they catch wind of a potential event.

“They end up finding out anyways,” Chaj-Perez said. “And then they end up calling us, emailing us, basically saying we have to meet with them before our protest, because they want to know what we’re doing. It’s something that I don’t really like to do, but I’ll do it just to ensure that all those students in our rallies are safe and ensuring that no one gets hurt. We know that this is a university, and that at any time, students can face repercussions for [their] actions. So we want to just keep our students safe.”

SDSU did reach out to her the morning of the protest to go over TPM policies, but Chaj-Perez said she opted not to meet with them this time due to many past meetings.

CSU’s interim TPM policy was enacted in November 2024 and is subject to annual review. The policy allows CSU campuses to restrict forms of expression that may disrupt university functions, such as limiting expressions to public hours, camping, “heckler’s veto,” weapons and concealment of identity.

“The systemwide policy spells out activities and use of university property, where they may occur, and how violations of the policy will be addressed,” said Amy Bentley-Smith, director of CSU media relations and public affairs. “The CSU will not ignore activities and uses that threaten the safety of students and employees, nor will it permit the disruption of the work of the university.”

However, Chaj-Perez still feels that these guidelines that limit where, when and how students can protest infringe on her organization’s rights.

“It is very much one of those things where, whenever they ask us, ‘So what exactly are you going to do? What are you going to talk about?’ it seems very controlling and limiting our free speech and our right to protest,” Chaj-Perez said. “With our rallies with bigger groups, they especially try to limit what we say, what we do, where we are and how loud we are, which I think very much is putting limitations on all of our rights to speak to free speech.”

Fourth-year studio arts student Riley, who did not want to disclose her last name due to safety concerns, was drawn to the protest after seeing it while walking by.

Balancing both sides of the political spectrum

Riley theorized that SDSU wants to be progressive, but has not spoken out about the Supreme Court ruling to not “offend their conservative students and staff.”

“[SDSU] considers itself a Hispanic-serving institution,” she said. “And I think if you’re gonna label yourself that you have to put in the work. I don’t think you can just say that and then never show up for Latinx people who are suffering a lot right now.”

Riley also highlighted the overlap between anti-immigration and pro-Palestine protests, of which M.E.Ch.A. has also verbalized in many of their protests.

“I think that they need to, at the bare minimum, release a statement regarding the SCOTUS ruling and regarding this campus being a safe place for DACA students and immigrant students. I think that’s the bare minimum,” Riley said. “I also think that everything’s tied together, and they should really divest from all of the Israeli ties that they have, because that’s tied in as well with Palestinian safety is tied in with immigrant safety, in my opinion.”

READ NEXT