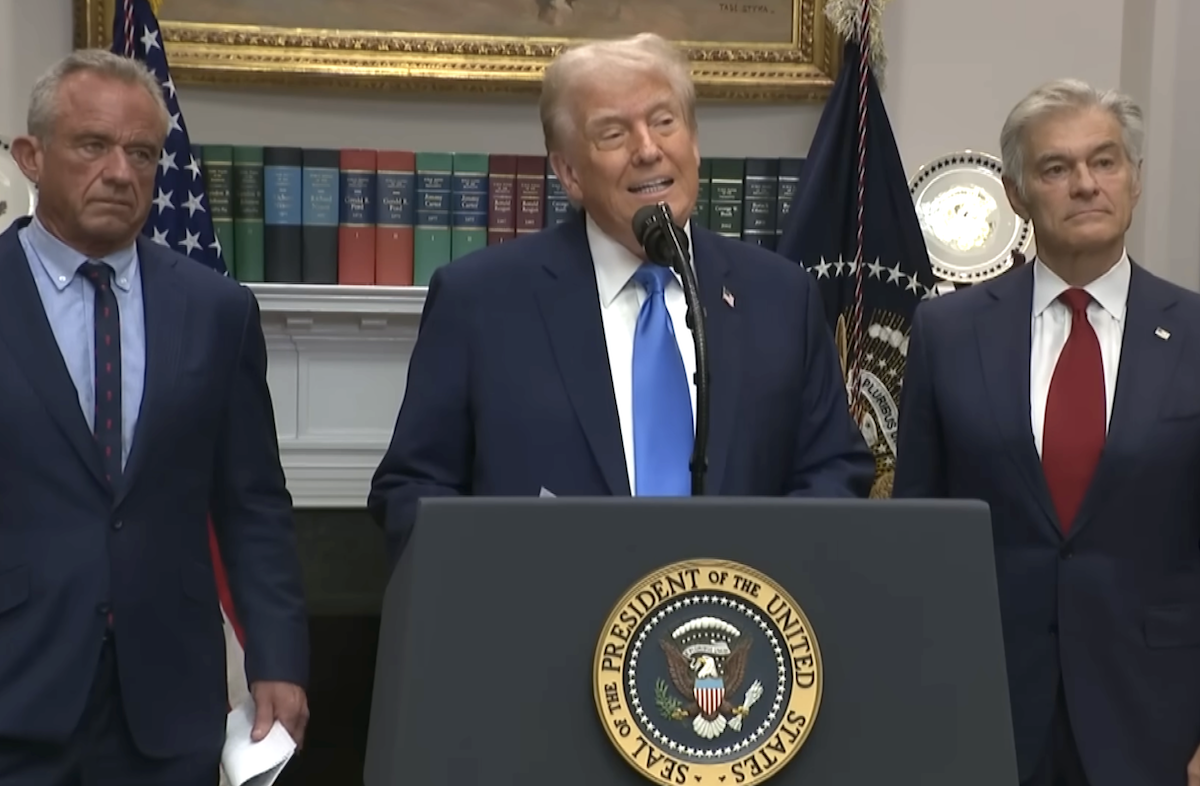

During a Sept. 22 press conference, President Donald Trump claimed that acetaminophen was linked to autism. Photo: Screenshot of press conference from WFAA YouTube channel captured Sept. 24, 2025

Journalists across the U.S. have been scrambling to keep up with a firehose of health misinformation coming from the administration since Monday’s Health & Human Services news conference debacle. Plenty of publications have already done a fantastic job of addressing the false or misleading claims by HHS Secretary Robert Kennedy and President Trump and providing more nuanced, evidence-based explanations of what people should understand about autism, acetaminophen use during pregnancy, and the medication leucovorin.

But the fallout from that news conference has made clearer what a string of previous federal health announcements and committee meetings have already been pointing toward: Journalists now have the challenging role of informing audiences about health-related news without relying on information from federal agencies such as the CDC and FDA. Here are some tips for this brave new world of helping audiences make informed decisions about their health when misinformation is coming from the top.

Acknowledge the reality of the moment

First, it’s essential that journalists are absolutely clear about the unreliability of information from agencies like the CDC and FDA. This is an uncomfortable place to be, after years of linking to and referring to pages from these formerly venerable agencies. But when officials in these agencies are so blatantly no longer relying on the actual evidence base to make policy, we have to assume that “data” from them is so tainted that none of it can be fully trusted — and audiences need to know that too. That means being extra cautious to avoid false balance and employing debunking and informing strategies that research has revealed to be effective in countering inaccurate information of all kinds.

In one sense, journalists have already had a dry run of this work. During the pandemic, Trump made many false statements about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 that journalists had to counter. Two differences make things both easier and harder now.

First, the coronavirus was new at the time, so uncertainty and lack of information made it more challenging to provide audiences with the information they needed, whereas many of the health topics being misrepresented now have amassed a wealth of reliable research. On the other hand, the misinformation then was focused almost entirely on COVID, whereas it now touches a far wider range of health topics. That calls for expanding the reporting resources journalists rely on beyond the infectious disease community.

Clearly explain risks and benefits while employing nuance as needed

The big takeaways that health reporters must convey include:

- That acetaminophen use during pregnancy has not been as clearly linked to autism as claimed in the HHS news conference, though this claim provides an opportunity to educate audiences about correlation vs. causation and the limits of observational studies, as Matthew Herper does in this STAT piece. The FDA’s news release does temper the claims somewhat, noting that “a causal relationship has not been established and there are contrary studies in the scientific literature.” Still, the same release attributes “a considerable body of evidence about potential risks associated with acetaminophen” to FDA Commissioner Marty Makary, even though the totality of the research suggesting an actual possible link is far from “considerable.”

- Acetaminophen treats certain conditions such as fevers that can pose risks to a fetus if untreated. Further, acetaminophen use can even help identify some high-risk pregnancy circumstances: headaches that do not respond to Tylenol may be the first indication of preeclampsia for some.

- The only consensus about autism’s causes firmly supported by existing research is its strong genetic component. Environmental factors likely contribute to some autism as well, but several decades of research have yet to identify clearly and definitively what those environmental influences may be, much less how they can be modified. Several with the strongest research backing are not environmental substances but factors such as advanced parental age, infection and fever — the last of which acetaminophen treats.

- That approving use of a new medication should require a high level of effectiveness and safety shown in randomized controlled trials, which leucovorin has not undergone for autism spectrum disorder. The FDA has announced it will be approving leucovorin “on the basis of new data” after previously rescinding its New Drug Application — yet the data described is neither new nor meets the typical thresholds previously required by the FDA for a new indication.

- The primary reason for an increase in autism diagnoses over the past 25 years has been the combination of expanded diagnostic criteria and greater awareness and identification of the condition.

- That vaccines continue to have no association with autism and that the CDC’s 2024 recommended schedule of immunizations has been thoroughly tested and shown not to have any risks associated with getting “too many vaccines too soon.”

- That research into autism encompasses far more than simply investigating the causes of the condition and best serves autistic people and their families when it focuses on effective supports and therapies related to autism.

Direct audiences to reliable sources of information

Because the CDC, FDA and other federal health agencies are no longer reliable sources of information, journalists should use and cite evidence-based sources and highlight the expertise they provide that diverges from the federal administration’s claims:

- Medical societies and physician organizations, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine have issued statements clarifying what the evidence actually shows and what physicians recommend based on the research.

- The health agencies of other high-income countries, particularly those that may have populations with similar demographics to populations in the U.S., can often provide reliable information. These include the English-language information in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia (here and here), and New Zealand.

- The research itself, which journalists can find in PubMed (which, for the moment, still appears reliable). AHCJ’s Medical Studies Core Topic page provides a wealth of resources journalists can use to read, understand and interpret medical studies.

- Finally, health condition nonprofits and advocacy organizations, despite having their own missions specific to that condition, can often help direct journalists to the best research. With autism organizations in particular, journalists should proceed with caution when deciding which ones to rely on for information and sources. This list from the Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism is a helpful resource of what to look for, including red flags and particularly useful organizations.