Soon after, when the legislature formally took up a bill to expand exemptions, three former state health officers released a letter warning that it would “weaken the hard-earned protections keeping our children, families, and communities safe.” Keith Marple, an eighty-one-year-old Republican delegate from Harrison County, urged fellow-lawmakers to vote it down, and spoke of people he’d known with permanent complications of polio. “We’re here today voting not just on one child . . . but on the thousands of children in West Virginia coming into school age,” he declared. “Are we going to protect them? Or are we going to let them take their chances?” This time, the legislation failed.

West Virginia is a rural state with limited health-care infrastructure; many families don’t have easy access to clinicians, and vaccination requirements create an impetus to engage with the medical system. “There’s a big concern that if we open up exemptions, we’re going to see these diseases roaring back,” Steven Eshenaur, the head of the Kanawha-Charleston Health Department, told me. The state’s extraordinary success in getting kindergarteners immunized belies a more complicated reality: immunization rates for toddlers, before the mandates apply, are among the lowest in the country. “The writing is on the wall,” Eshenaur said. “If parents don’t have to do it, it’s probably not going to happen.”

Morrisey hasn’t withdrawn his executive order, which conflicts with the state’s immunization law, and has generated confusion and uncertainty. The state’s health department has granted hundreds of vaccine exemptions, while members of the Board of Education have unanimously decided to effectively ignore those exemptions. (Justice has called Morrisey’s actions “plain out and out nuts.” Morrisey, in turn, derided Justice for holding a “very liberal position.”) In May, some parents filed a lawsuit alleging that the governor’s order placed immunocompromised children at risk; the mother of a ten-year-old boy with a serious genetic disorder said, “Something as simple as a common cold, that is not simple for him.” Then a registered nurse named Miranda Guzman brought a rival lawsuit, after her child’s school refused to honor a religious exemption. Morrisey’s executive order doesn’t require parents to explain their religious objection, and no major religion expressly forbids vaccination. (In the complaint, Guzman says that she believes it’s wrong to needlessly interfere with her child’s “God-given natural immune” system.) “It is precisely religious people who should want to see the citation in scripture—who should want chapter and verse,” Christopher Martin, a public-health professor at West Virginia University, told me. “Your grandparents were Christian, and they got vaccinated, didn’t they?”

The movement to weaken the state’s decades-old vaccination requirements is enmeshed with Kennedy’s orbit. Aaron Siri, a Kennedy ally, is one of Guzman’s lawyers, and the lawsuit is funded in part by the Informed Consent Action Network, an anti-vaccine organization founded by Kennedy’s former communications director. Last month, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights sent West Virginia an unusual letter, apparently threatening to withhold more than a billion dollars in funding if the state’s health departments fail to grant exemptions outlined in the governor’s executive order. “I stand with @WVGovernor Patrick Morrisey,” Kennedy posted on X.

West Virginia’s success in keeping children safe from vaccine-preventable illnesses highlights the singular power of immunization. Many of the struggles that children face—obesity, isolation, mental-health challenges—are knotty problems without easy answers. But a single policy can protect them from many infectious threats. With the federal government in retreat, vaccine wars have shifted to the states, and individual leadership can make a pivotal difference. Justice and Morrisey are both Republicans, but one expended political capital to preserve vaccination requirements while the other aims to weaken them. A judge has issued a preliminary injunction, allowing children of the plaintiffs in the Guzman case to attend school this fall, and soon West Virginia’s Supreme Court will hear arguments about whether school officials should follow the state’s legislature or its governor. Its decision will serve as a test of whether an unlikely state can continue to lead the way.

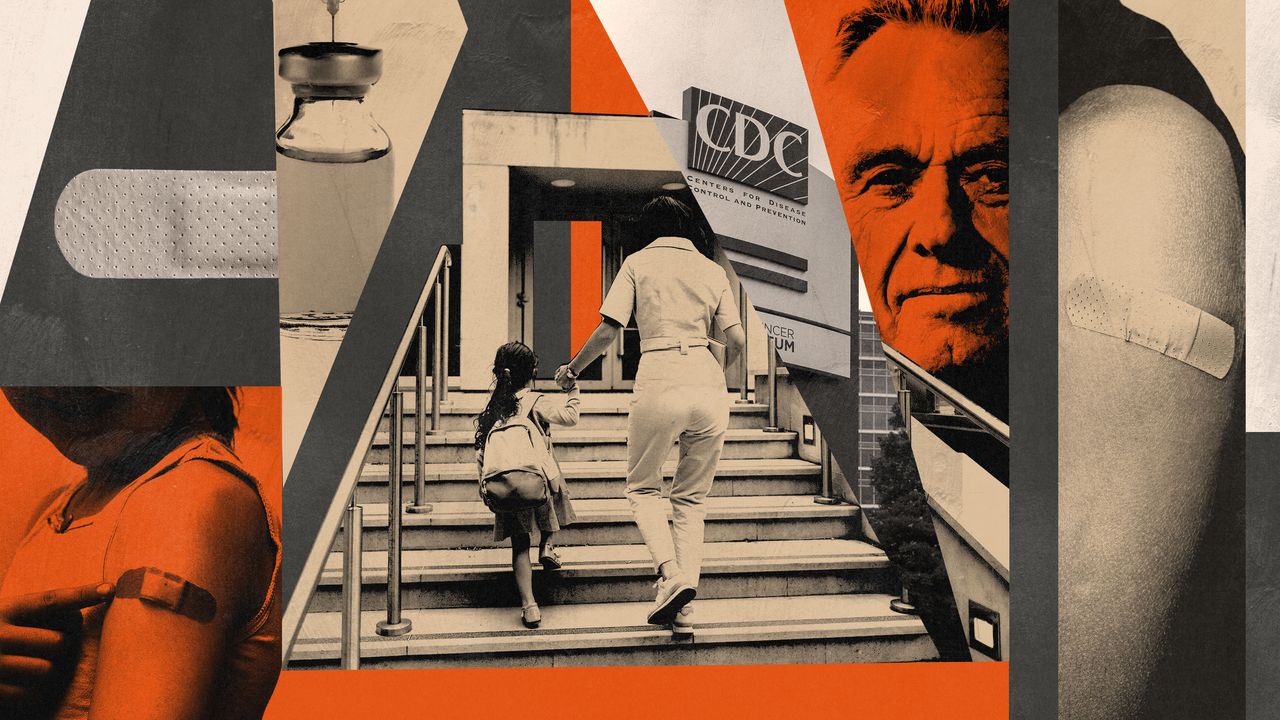

In the U.S., public-health authority rests largely with the states. Within their borders, states have broad power to issue quarantines, enforce curfews, regulate businesses, require seatbelts, and license medical professionals. For decades, they’ve moved more or less in lockstep on issues of immunization, using the C.D.C.’s recommendations to develop their requirements for entry into schools, day cares, and other communal spaces. Since the nineteen-eighties, every state has required that virtually all school-age children get vaccinated against diseases such as polio, measles, and tetanus. The C.D.C. estimates that routine childhood vaccination in the U.S. has saved more than a million lives, averted hundreds of millions of illnesses, and led to trillions of dollars in societal savings.

The nation’s vaccination apparatus was already fraying before the rise of MAHA. Since 2019, vaccination rates have fallen in about three-quarters of U.S. counties, according to an NBC News-Stanford analysis, and more than half of them have experienced at least a doubling in the level of vaccine exemptions. Research consistently shows that exemptions result in a higher rate of vaccine-preventable diseases. One study found that kids who received exemptions were twenty-two times more likely to contract measles and nearly six times as likely to get whooping cough.

Instead of motivating a federal approach to shared problems, America’s increasingly nationalized politics have led to a fracturing of public-health policy. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have all recently issued recommendations that conflict with vaccine guidance from the federal government. This month, America’s Health Insurance Plans, the nation’s largest association of health insurers, announced that through the end of 2026 its member plans would cover all shots recommended by the C.D.C.’s vaccine-advisory panel prior to the recent meeting. Democratic-led states are taking steps to protect access to vaccines. Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey said that the state would require insurers to cover immunizations recommended by its health department. California, Oregon, and Washington have created an alliance to develop vaccine recommendations, and New Mexico recently authorized pharmacists to deliver COVID-19 shots based on its own guidelines. The state’s health secretary said that it “cannot afford to wait for the federal government to act.”